Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper, USNR, (1906-1992)

Grace Murray (Hopper) was born in New York City on 9 December 1906. She graduated from Vassar College in 1928 and received a PhD in Mathematics from Yale University in 1934. She was a member of the Vassar faculty from 1931 to 1943, when she joined the Naval Reserve. Commissioned a Lieutenant (Junior Grade) 1944, she was assigned to the Bureau of Ordnance and immediately became involved in the development of the then-embryonic electronic computer. Over more than four decades to follow, she was in the forefront of computer and programming language progress.

Leaving active duty after the war's end, Dr. Hopper was a member of the Harvard University faculty and, from 1949, was employed in private industry. She retained her Naval Reserve affiliation, attaining the rank of Commander before retiring at the end of 1966. In August 1967, Commander Hopper was recalled to active duty and assigned to the Chief of Naval Operations' staff as Director, Navy Programming Languages Group. She was promoted to Captain in 1973, Commodore in 1983 and Rear Admiral in 1985, a year before she retired from the Naval service. She remained active in industry and education until her death on 1 January 1992.

USS Hopper (DDG-70) is named in honor of Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper.

She was a mathematician and a pioneer in the use of computers in the military, particularly in the United States Navy. She was one of the inventors of the computer language “COBOL” and was the first person to use the word “bug” to describe an error in a computer program.

She is buried in Section 59 of Arlington National Cemetery.

December 27, 1994

Legacy of Amazing Grace, the computer ace

The interesting thing about the computer industry is how diverse its people are. The other day, my wife and I attended a Christmas party that was packed with people who, in one way or another, have made computers their business.

One was a former journalist, another a NASA employee who had left the agency to pursue a career in Internet activities. Some of the people I spoke to had purposely taken computer courses in college, envisioning a career in the field; others, like me, had come to technology out of serendipitous interest and curiosity.

What that says, I think, is that computers are approachable. Anyone with a thousand dollars to spend can get up and running with a system that can teach him or her the basics of programming or interface design or networking in the privacy of home or office.

Of course, it wasn't always that way, and as I stood there with a glass of champagne, I couldn't help thinking about Grace Hopper, who was about as unlikely a role model for the average computer guru as you could find. More than anyone I know, she made widespread computing possible.

”Amazing Grace,” as she was known, was a tiny woman whose unceasing labors on behalf of computer education helped transform the way we look at data processing. She is one of those critical figures who occasionally appear in history at just the right time to influence an ongoing sea-change and turn it unmistakably in their direction.

Grace graduated from Vassar and earned a Ph.D. in mathematics from Yale. This was during World War II and she next was commissioned a lieutenant junior grade in the WAVES. She began working on computers by chance, at the Bureau of Ordnance Computation Project at Harvard.

If it's not immediately apparent how ordnance figures into the history of computing, be advised that one of the crucial spurs to growth in our knowledge of the field came from the attempt to understand the flight path of artillery shells. The mathematics of such computations is complex, requiring the services of a machine called the Harvard Mark I, which some have called the first fully functional digital computing device. Get this – the Mark I contained not just 500 miles of electrical wire, but a whopping 750,000 parts, all of which Grace Hopper used to crank out ballistic tables for the Navy's weaponry.

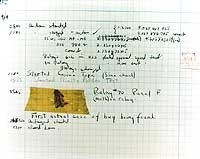

You run into Grace's presence everywhere you turn in modern computing. The term ”bug” used to describe a flaw in software code traces back to the day in 1945 when she took the Mark I's successor, the Mark II, apart to find out why it had stopped working. The answer: a moth that had become caught between crucial contacts on one of the computer's relays. The moth carcass was taped into the project's log book with this inscription: ”First actual case of a bug being found.”

And there you have it, the short path to linguistic immortality. Fixing computer problems would forever be known as ”debugging.”

Now, in the Naval Reserves, Grace went to work for the Eckert-Mauchly Corp. in Philadelphia, where her project was UNIVAC, the first electronic commercial computer. Those were the days when computers were treated like oracles; it was assumed that only the high priesthood of computer scientists could ever draw useful information from the machines. The idea that ordinary people like you and me would someday use computers would have struck most professionals as a fantasy.

Those in the field in that era didn't mind if their work seemed beyond comprehension. After all, pushing a mainframe around gives you a certain degree of prestige, not to mention control over those who must come to you with their data processing needs. I can imagine, too, how difficult this male-dominated clique must have made life for the diminutive New Yorker, but she faced the challenge (and won over everyone she worked with) with characteristic resolve and good cheer.

By 1955, she had produced the prototype for COBOL. COBOL is a programming language, and in its own way, a revolution. Short for Common Business Oriented Language, COBOL quickly became a lingua franca for modern business; it was, after all, designed to retrieve accounting, billing and payroll information. Better still, the program was easy to use, and sent the message that computers could perform many business tasks that heretofore had been passed along to specialists. The broader principle , one that Grace insisted upon throughout her life, was that computers should be available to anyone who needed them. Her work led directly to that result.

Grace went on to spend two decades reorganizing the computing resources of the U.S. Navy, putting in as many as 300 days a year traveling and giving lectures. She died in 1992 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, having become the first woman to hold the rank of rear admiral. The Navy, fittingly, has named its Data Automation Center in San Diego after her, and has also commissioned a new destroyer in her honor, the U.S.S. Hopper. Her broader legacy, of course, is on desktops acros s the world, in the form of the computers she helped make accessible to business and personal users alike.

Moth found trapped between points at Relay # 70, Panel F, of the Mark II Aiken Relay Calculator while it was being tested at Harvard University, 9 September 1945. The operators affixed the moth to the computer log, with the entry: “First actual case of bug being found”. They put out the word that they had “debugged” the machine, thus introducing the term “debugging a computer program”. In 1988, the log, with the moth still taped by the entry, was in the Naval Surface Warfare Center Computer Museum at Dahlgren, Virginia

Read here our most popular Post:

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard