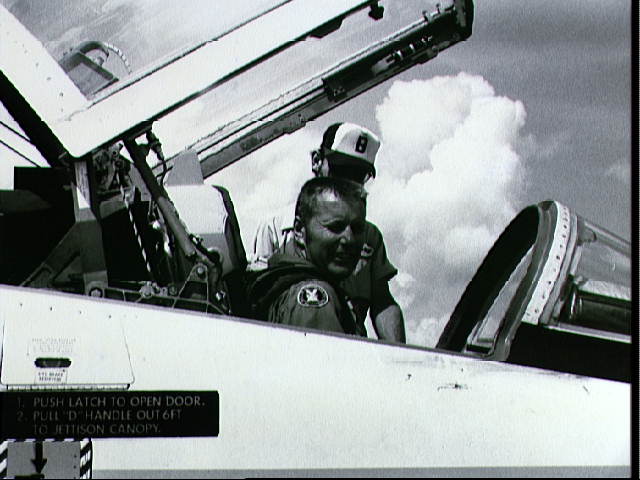

Retired Marine Colonel Robert F. Overmyer, was interred in Arlington Nationa Cemetery (Section 23, Grave 22469) following his death March 22, 1996.

Overmyer piloted STS-5, the first fully operational flight of the space shuttle, November 11, 1982, when the Payload Assist Module was first used, launching two commercial satellites. He commanded STS 51-B, a Spacelab mission, in 1985. After serving on the inquiry panel following the Challenger disaster, Overmyer retired from the military and died in the crash of an experimental civilian aircraft he was test piloting.

Courtesy of The National Aeronautics & SpaceAdministration (NASA)

NAME: Robert F. Overmyer (Colonel, United States Marine Corps, Retired)

NASA Astronaut (Deceased)

PERSONAL DATA:

Born July 14, 1936, in Lorain, Ohio, but considered Westlake, Ohio, his hometown.

He died on March 22, 1996. He is survived by his wife, Katherine, and three children. Hobbies included skiing, water skiing, boating, acrobatic flying in open cockpit biplanes, coaching baseball, and running.

EDUCATION:

Attended and graduated from Westlake High School, Westlake, Ohio, in 1954. Received a bachelor of science degree in Physics from Baldwin Wallace College in

1958. Received a master of science degree in Aeronautics with a major in Aeronautical Engineering from the U. S. Naval Postgraduate School in 1964.

ORGANIZATIONS:

Member of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots, Experimental Aircraft Association, and Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association.

SPECIAL HONORS:

Awarded the U.S. Air Force Meritorious Service Medal in 1969 for duties with the USAF Manned Orbiting Laboratory Program; awarded the USMC Meritorious Service Medal in 1978 for duties as the Chief Chase Pilot and support crewman for the Shuttle Approach and Landing Test Program; received an Honorary Doctor of Philosophy degree from Baldwin Wallace College, December 1982; awarded the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School Distinguished Engineers Award, January 1983; the U.S. Marine Corps Distinguished Flying Cross (1983); and the NASA Space Flight Medal (1983).

EXPERIENCE:

Colonel Overmyer entered active duty with the Marine Corps in January 1958. After completing Navy flight training in Kingsville, Texas, he was assigned to Marine Attack Squadron 214 in November 1959. Colonel Overmyer was assigned to the Naval Postgraduate School in 1962 to study aeronautical engineering. Upon completion of his graduate studies, he served 1 year with Marine Maintenance Squadron 17 in Iwakuni, Japan. He was then assigned to the Air Force Test Pilots School at Edwards Air Force Base, California. Colonel Overmyer was chosen as an astronaut for the U.S. Air Force Manned Orbiting Laboratory Program in 1966. The program was canceled in 1969. Colonel Overmyer has over 7,500 flight hours with over 6,000 in jet aircraft.

NASA EXPERIENCE:

He was selected as a NASA astronaut in 1969 after the MOL Program was canceled. His first assignment with NASA was engineering development duties on the Skylab Program from 1969 until November 1971. From November 1971 until December 1972, he was a support crew member for Apollo 17 and was the launch capsule communicator. From January 1973 until July 1975, he was a support crew member for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project and was the NASA capsule communicator in the mission control center in Moscow, USSR. In 1976, he was assigned duties on the Space Shuttle Approach and Landing Test (ALT) Program and was the prime T-38 chase pilot for Orbiter Free-Flights 1 and 3.

In 1979 Colonel Overmyer was assigned as the Deputy Vehicle Manager of OV-102 (Columbia) in charge of finishing the manufacturing and tiling of Columbia at the Kennedy Space Center preparing it for its first flight. This assignment lasted until Columbia was transported to the launch pad in 1980.

Colonel Overmyer was the pilot for STS-5, the first fully operational flight of the Shuttle Transportation System, which launched from Kennedy Space Center, Florida, on November 11, 1982. He was accompanied by spacecraft commander Vance D. Brand, and two mission specialists, Dr. Joseph P. Allen and Dr. William B. Lenoir. STS-5, the first mission with a four-man crew, clearly demonstrated the Space Shuttle as fully operational by the successful first deployment of two commercial communications satellites from the Orbiter’s payload bay. The mission marked the first use of the Payload Assist Module (PAM-D), and its new ejection system. Numerous flight tests were performed throughout the mission to document Shuttle performance during launch, boost, orbit, atmospheric entry and landing phases. STS-5 was the last flight to carry the Development Flight Instrumentation (DFI) package to support flight testing. A Getaway Special, three Student Involvement Projects and medical experiments were included on the mission. The STS-5 crew successfully concluded the 5-day orbital flight of Columbia with the first entry and landing through a cloud deck to a hard-surface runway and demonstrated maximum braking. Mission duration was 122 hours before landing on a concrete runway at Edwards Air Force Base, California, on November 16, 1982.

Colonel Overmyer was the commander of STS 51-B, the Spacelab-3 (SL-3) mission. He commanded a crew of 4 astronauts and 2 payload specialists conducting a broad range of scientific experiments from space physics to the suitability of animal holding facilities. Mission 51-B was also the first Shuttle flight to launch a small payload from the -Getaway Special” canisters. Mission 51-B launched at 12:02 p.m. EDT on April 29, 1985 from Kennedy Space Center, Florida, and landed at Edwards Air Force Base, California, at 9:07 a.m. PDT on May 6, 1985. Mission 51-B completed 110 orbits of the earth at an altitude of 190 n.m.

Colonel Overmyer retired from NASA and the Marine Corps in May 1986.

Colonel Overmyer died on March 22, 1996, in the crash of a light aircraft he was testing.

After spearheading recovery operations following the Challenger disaster, Colonel Overmyer retired from the Astronaut office and the Marine Corps in May of 1986 to commence his own consulting business, Mach Twenty Five International, Inc. He consulted to major aerospace corporations and the National Broadcasting Corporation (NBC) as well as writing a column for the British Magazine, _Space Flight News. In March of 1988, he joined the Space Station Team at McDonnell Douglas Aerospace, where he led crew and operations activities for seven years.

He retired from McDonnell Douglas in April 1995 and expanded the scope of Mach Twenty Five International, continuing his aerospace consultation work as well as speaking engagements and writing.

With his wife, Kit, and children Carolyn, Patty, and Robert, he enjoyed tennis, golf, and most any athletic activity, especially flying, flying, and flying. In addition to logging air time in both his Mooney and his Starduster Too, he continued to use his test pilot skills and wrote about his flight experiences in “Time In Type”, a column published monthly in AOPA Pilot Magazine.

Colonel Overmyer perished in a tragic accident on 22 March 1996, in Duluth, Minnesota, while test flying an experimental kit airplane. He died doing what he loved to do, and we know he would want us to be happy about that. He was a quintessential family man and an inspiration to all who knew him. We have all lived our lives a little bit better because of his example.

Mission Summary

STS-5

STS-5, the first operational mission, also carried the largest crew up to that time — four astronauts — and the first two commercial communications satellites to be flown.

The fifth launch of the orbiter Columbia took place at 7:19 a.m. EST, Nov. ll, l982. It was the second on-schedule launch. The crew included Vance Brand, commander; Robert F. Overmyer, pilot; and the first mission specialists to fly the Shuttle — Joseph P. Allen and William B. Lenoir.

The two communications satellites were deployed successfully and subsequently propelled into their operational geosynchronous orbits by booster rockets. Both were Hughes-built HS-376 series satellites — SBS-3 owned by Satellite Business Systems, and Anik owned by Telesat of Canada. In addition to the first commercial satellite cargo, the flight carried a West German-sponsored microgravity GAS experiment canister in the payload bay. The crew also conducted three student experiments during the flight.

A planned spacewalk by the two mission specialists had to be cancelled — it would have been the first for the Shuttle program — when the two space suits that were to be used developed problems.

Columbia landed on Runway 22, at Edwards AFB, on Nov. 16, l982, at 6:33 a.m. PST, having traveled 2 million miles in 8l orbits during a mission that lasted 5 days, 2 hours, 14 minutes and 26 seconds. Columbia was returned to KSC on Nov. 22.

Couresy of the National Transportation Safety Board

CHI96FA116

HISTORY OF FLIGHT

On March 22, 1996, at 1220 central standard time (cst), an Experimental Cirrus VK30, N44VK, piloted by a commercial pilot, was destroyed after a collision with terrain, following an uncontrolled descent. The commercial rated pilot was fatally injured in the accident. Visual meteorological conditions prevailed at the time of the accident. The 14 CFR Part 91 flight was not operating on a flight plan. The airplane was on a local test flight, attempting to validate stall characteristics with different settings of wing flaps and landing gear. The pilot of the chase airplane, and the on board video camera confirmed that N44VK departed controlled flight before impacting the terrain.

FLIGHT RECORDERS

A video camera on board N44VK was recording the reactions of yarn tufts attached to the upper surface of the right wing during stalls. The video tape's case and tape were damaged during the accident. On Sunday, March 24, 1996, at the office of Pro Video Productions, Duluth, Minnesota, the original video was repaired. All of the tape was recovered except for approximately one second at the end of the tape. The video tape ends before N44VK impacts with the terrain. A video technician stated that during the maneuver the tape most likely pulled away from the heads of the recorder, causing the recorder to terminate recording. The unedited duplicate of this tape is included as an attachment to this report.

WRECKAGE AND IMPACT INFORMATION

The airplane came to rest in a upright position on a magnetic heading of 150 degrees. The coordinates obtained from a police global positioning satellite system were north 46 degrees 56.12 minutes, and west 92 degrees 11.91 minutes. Using a police inclinometer the descent angle was measured at 77 degrees.

All of the airframe components recovered were found within 30 feet of the main wreckage. The top portion of the right side door was not located, until several weeks after the on scene investigation. The hinge which attached the door to the fuselage was bent, and the gas spring which held the door in the open position was bent with one end missing.

The right landing gear was extended and attached to the wing. The left landing gear was separated from the left wing. The gear selector switch was found in the down position. The wing flaps were down at approximately one quarter deflection. All control surfaces and balance weights were found attached. Airspeed indications were 160 knots indicated airspeed on the copilot's side, 136 knots indicated airspeed pilot's side. The pilots seat was bent into a U shape. The horizontal stabilizer was found near the maximum leading edge up position.

All three wooden blades of the variable pitch propeller had sustained damage. The drive shaft between the engine's gear box, and the propeller hub showed signs similar to a torsional overload failure. The gear box casting was cracked. Black marks similar in color to the drive shaft dampener were seen on the floor beneath the drive shaft.

MEDICAL AND PATHOLOGICAL INFORMATION

An autopsy was performed on March 23, 1996 at the St. Luke's Hospital, in Duluth, Minnesota. The toxicological testing performed by the Federal Aviation Administration in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, was negative for all items tested.

TESTS AND RESEARCH

Before moving the aircraft all engine and airframe controls were checked for continuity. The aileron system was continuous from the chain in the cockpit to both ailerons on the wing. The chain in the cockpit area was broken, and the broken chain link showed evidence similar to an overload failure. Both ailerons could be actuated by pulling on the cables in the cockpit. The on board video showed the right aileron moving during the airplane's descent.

The elevator system was continuous from the cockpit to the rod end on the elevator. The elevators could be actuated by using the control cables in the cockpit. The rudder push-pull cables were found still attached to the rudder pedals, and the rudder could be actuated in the cockpit using the push-pull cables.

The jack screw which controls the horizontal stabilizer position was found attached, and it operated when a 24 volt battery charger was attached. Both flap jack screws were found attached to their mounts and during the video taping of the stall series,

the right flap appeared to operate normally. No evidence of any preexisting rubbing, binding or chaffing was found on any control surface of the aircraft.

All engine controls were found attached at the control quadrant in the cockpit, and in the engine compartment. The engine oil and fuel filters were both clean and showed no evidence of contamination. The engine's compressor blades showed evidence of rubbing on the compressor case. The red indicator on the scavage filter case was extended, and the airframe oil scavage pump filter contained numerous pieces of contamination.

Two chip detectors from the engine were removed. Both chip detectors were filled with metal chips, and had continuity when checked with a volt-ohm meter. The engine gear box chip detector was removed, and tested positive for continuity when checked with a volt-ohm meter. At this point in the investigation the engine, gear box and engine filters were crated up, and shipped to the engine manufacturers facilities in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Investigation of the engine at the manufacturer's facilities on July 8, 1996, revealed no abnormalities with the engine, and indications of power at impact were evident throughout the engine. The engine inspection report is included as a supplement to this report.

ADDITIONAL DATA/INFORMATION

The pilot of N44VK was attempting to verify the stall characteristics of this airplane with the center of gravity at 33 percent mean aerodynamic chord, which was intended to be the aft center of gravity limit for this airplane. The pilot's log book contained an entry for a flight from the previous day for .9 hours, with the center of gravity at 33% mean aerodynamic chord. During the last stall, N44VK was configured with the landing gear down, and the flaps fully extended.

A former test pilot who had worked with Cirrus Aircraft was contacted by the IIC on April 8, 1996. The former test pilot recalled three occasions while he was testing the piston engine version of the VK30, where the aircraft departed controlled flight. The former test pilot said that with the flaps extended 40 degrees and the landing gear down the aircraft did not recover as well from stalls when compared with clean configuration stalls. The former test pilot said that the stick force gradient was positive, but very light during all stall tests. The former test pilot said that the original prototype aircraft had differences in the amount of wash-out between the left and right wings, which may have contributed to the departure characteristics.

On April 3, 1996, a group of six NASA employees who specialize in high angle of attack and spin research reviewed the video tape showing the departure from controlled flight of N44VK. The group said that when the yarn tufts were indicating air flow toward the leading edge of the right wing, it was a result of a very high angle of attack, and was not uncommon to see during spin research. The group agreed that the aircraft's pitch attitude decreased, during the departure.

The airplane was not equipped with any antispin or deep stall recovery devices.

Parties to the investigation were the Federal Aviation Administration, Cirrus Design, Allison Engines and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard