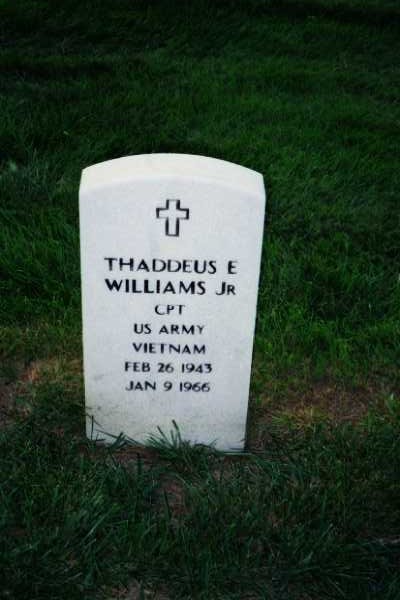

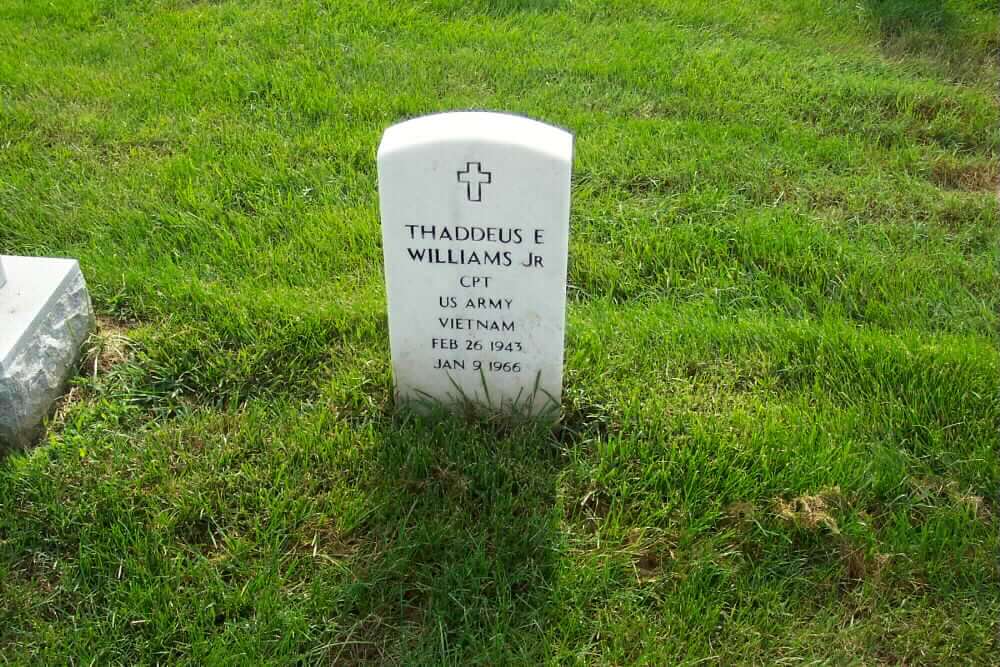

He was born on February 26, 1943 and was from Mobile, Alabama.

Courtesy of the Defense News Agency: 26 February 1999:

More than 2,000 Vietnam-era soldiers remain missing, and an Army laboratory is working on identifying several hundred sets of remains. The new DNA analysis means that it is theoretically possible to identify virtually any recovered body if the military can find likely living relatives and compare their genetic material, officials said.

That's what has been happening with the remains being repatriated from Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, including two Army soldiers being buried at Arlington this morning. Captain Thaddeus E. Williams Jr. and Specialist 5 James Schimberg have been missing since their aircraft went down over Phu Yen province in Vietnam in 1966, and the Army lab was recently able to link them conclusively to remains brought back to this country in 1993, Army officials said.

When Eldridge Williams and his big brother, Thaddeus, were little boys in Mobile, Alabama, a birthday party meant playing games out in the yard and eating ice cream and cake.

They didn’t play games Friday, the day that Thaddeus would have been 56 years old if he hadn’t died on a cloud-shrouded mountainside in Vietnam.

Instead, two families and many friends celebrated his life and the life of Jim Schimberg of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, who died together in a small reconnaissance plane 33 years ago.

They celebrated with tears and prayer, with the magic of memory and the relief of laughter – and the strong bonds that bind those who have shared more than a quarter of a century wondering if they’d ever find out what happened to two young men on that sad night during a war a world away.

Instead of games, ice cream and birthday cake, they celebrated Thaddeus and his friend with the sombre echo of horses and caisson wheels, with flag-draped coffins at twin graves, with a three-volley gun salute, a drum roll, with a mournful bugle playing taps.

And now they’ll never forget a weekend in February that was a reunion and a lovefest, filled in by eulogies, hymns, full military honors and a funeral at Arlington National Cemetery in the shadow of the nation’s capital. It won’t be the final chapter in a story that seemed to end on January 9, 1966.

That night, Captain Thaddeus Edward Williams was flying a combat surveillance mission over Phu Yen Province in the Republic of South Vietnam when his navigation system went out.

The captain, who had finished his architectural studies at Tuskeegee Institute and was fulfilling his ROTC commitment, and his only crew member, Spec. 4 James P. Schimberg, a photographer, were forced to fly their Mohawk by ‘‘dead reckoning.’’

Weather was bad, the clouds low.

They last radioed at 2400 hours – midnight – on Jan. 9, 1966.

‘‘The aircraft,’’ the Army later told the family, ‘‘never returned to home base, and search attempts discovered no evidence of either the aircraft or the crew.’’

A year later, the Army declared them missing in action. Their official records said: ‘‘Presumed dead, bodies not recovered.’’

Until August 1993.

Then a team from the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii went to Vietnam with new information. Two Vietnamese informants who live in Ho Chi Minh City had found eight to 10 bones and dog tags on a mountainside close to the South China Sea.

They described a burned identification card bearing the picture of a black man and the name Thaddeus Williams.

They wouldn’t talk about the crash site or take the team to it.

But the Army did a full investigation, comparing DNA from the recovered bones of both men and blood samples taken from family members last year and proved their identity. And the number of missing American servicemen in Vietnam accounted for since 1973 rose to 510.

That still leaves 2,073 missing in action from that war.

By the day after Christmas, final arrangements were being made to bury them side by side in Arlington on Friday, February 26.

And that’s what happened – after a visitation Thursday night and a chapel service Friday morning and the traditional military service under a blue sky on a winter day.

Three generations gather

The years have claimed their parents. Time has extended their families. And tradition followed a nontraditional reunion as new grandparents and children gather at the hotel near the cemetery – Thaddeus’ brother, Eldridge Williams, and his family, Brenda and their children, Demond, 21, Thad, 7, who is named for his uncle, and Janoah, 6, from Salisbury, and his late sister’s only child, Phillippa Stephens, of Oakland, Calif. And friends from the District of Columbia, Virginia, Alabama, Colorado and South Carolina.

And Jim Schimberg’s only living brother, Joe, of Des Moines, Iowa, and his three sisters, Pat and the twins, Carol and Linda, and their children and their children’s children and in-laws and cousins and friends from Iowa, Missouri, Louisiana, Illinois and Texas.

A crowd of more than 50 congregate at the hotel, prompting attendants and the families themselves to notice and exclaim.

‘‘Unfortunately,’’ says Phillippa, as they gather to go to the Arlington Funeral Home for visitation, ‘‘this is how it works. This is how people get together – when someone dies. Hopefully, out of it will come traditions.’’

When someone dies …

The words echo because that’s what it feels like over and over again on Thursday and Friday. Not, ‘‘when someone died.’’

‘‘I was amazed,’’ Jim Schimberg’s niece says, ‘‘that they could be identified, and I always assumed that he was gone. But my mom – it was like he had just died. She mourned. And she said, ‘In the back of your mind, you hope that maybe it was amnesia and … ‘ It was like there was always a light in the window, waiting.’’

Over and over tears bubble to the surface. Until now, they tell each other, they thought maybe he was still a prisoner of war, maybe, maybe, maybe …

Now they know – and they mourn.

And that’s why Joe Schimberg asked if they could have a visitation even though Arlington is no one’s home town and hundreds of friends won’t come to honor these two fallen soldiers. But the family needs a time, a place to get together, to have prayer, to meditate.

So they go to a funeral home, to two rooms, with two flag-draped caskets, and they share pictures and memories and prayer.

Thoughtful answers

Eldridge Williams stands before his brother’s casket with his children and tries to answer their questions.

‘‘Is his body in the casket?’’ 7-year-old Thad asks.

‘‘His bones are in the casket,’’ Eldridge tells him.

‘‘He’s in heaven,’’ 6-year-old Janoah explains.

And Eldridge, like people always do at visitations, remembers other days when he and his brother, who was four years older, shared a room.

‘‘We used to lay in the bunk beds and talk a lot,’’ he says. ‘‘He taught me a lot about jazz and tennis … I always wanted to be like him. He was smarter … ‘’

They played together in their close-knit neighborhood in Mobile, Alabama, and at the black YMCA their father, the Rev. Thaddeus Williams Jr., managed.

And in 1965 Thaddeus went to Vietnam, and Eldridge came to Livingstone, and they wrote each other letters until early ‘66. Then Eldridge’s letters started coming back. And Thaddeus’ letters stopped.

And two fathers – a black father in Alabama, a white father in Iowa – started writing to each other, calling each other, comforting each other, growing together as they shared their loss and hope.

When do you stop hoping?

‘‘I don’t know if I ever did,’’ Eldridge says. You think about prison camps and politics, ‘‘and when that Japanese soldier was found after years of being in the mountains – you tell yourself, maybe there was a possibility.’’

The people in the two rooms mingle, talk, meet Congressman Sanford Bishop, who was one of those neighborhood children back in Alabama, hold hands and hear Chaplain (Maj.) Bill Jokela pray.

‘‘We pray that nothing but good will come out of this,’’ he says, his head bowed, ‘‘and pray for families who still grieve, who don’t know.’’

Ties already tight grow tighter over dinner. When that plane crashed, Eldridge Williams and Joe Schimberg were both four years younger than their brothers, both freshmen in college, both sure they weren’t as smart.

And tighter yet over a cup of coffee together at the hotel Friday morning and riding in the big black limousines to the Old Post Chapel at Fort Myer together.

And crying together.

‘‘We’re all related through Vietnam,’’ says Rick Ullman, a stranger from Iowa. He’s the same age Thaddeus and Jim would have been, but he didn’t go to Vietnam, so he had to be here today.

‘‘Perhaps Thaddeus or Jim took my place,’’ he says, ‘‘and it’s my responsibility to say thank you.’’

Inside the chapel

Bright sunlight on this cold, cold day, after another day of spitting snow, filters through stained glass windows and warms the chapel – and emotion is palpable. Voices break. More than 70 people wait while eulogists struggle to get control.

Congressman Bishop remembers his last conversation with Thaddeus Williams.

‘‘We said goodbye, and I never dreamed that I would never have another opportunity. I can remember Thaddeus teaching me to hold a tennis racket. … He was a mentor, a friend, a hero …’’

The fathers established a relationship that still exists with their children, Eldridge Williams says.

If they were here, they, too, would thank the U.S. government for its persistence.

But his voice breaks.

A long silence fills the chapel.

Then he goes on.

‘‘I wish the world really knew what friendship means, what a village’’ like that of his childhood means, what extended family means.

‘‘I always wondered why God took Thad. He was my big brother, the intelligent one. I just hope and pray I can be like him.’’

‘‘Servicemen belong to us all,’’ says Tom Dostal, a Schimberg cousin. ‘‘We cannot thank you for what you did. We can only love you for it.’’

Joe Schimberg remembers the summer of 1960 when Jim graduated from high school and announced he had chosen to become a Trappist monk.

‘‘He always seemed to choose the ultimate in commitment and sacrifice. It was a difficult summer for our family.’’

Being a Trappist monk meant never seeing or talking to the family again.

But 18 days later, he was home again. Trappist life was not for him.

‘‘I ran across the room, put my arms around him and said, ‘Jim, you’re home! You’re home! Welcome home!’

‘‘That thought keeps recurring to me now.’’

And the time has come for a slow trip to two graves. An Army band plays ‘‘Nearer, my God, to Thee’’ and ‘‘America, the Beautiful.’’

‘‘At times old verses take on new meaning,’’ the chaplain says, as he begins to read, ‘‘The Lord is my shepherd … ‘’

A drum rolls. A bugle wails. Flags are folded flags. It is time for goodbye.

A plane rises high into a blue, blue sky and disappears into a bank of clouds.

The wind is picking up.

Brenda Williams tucks the hood of her 6-year-old daughter’s jacket closer to shield her from the cold.

‘‘It’s been such a long journey,’’ says Pat Schimberg Pigott. ‘‘We began 33 years ago and it finally … ‘’

She stops.

‘‘I don’t like to say ‘closure.’ It’s not closure. A transformation is taking place. It’s come full circle. And from any bad situation, good can come.’’

The Williams and Schimberg families have their brothers – Thaddeus, not 56, even on his birthday, but forever 22, and Jim, who’ll always be a 23-year-old who typically and forever chose commitment and sacrifice.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard