Another significant part of the World War II generation is gone now that Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist Bill Mauldin is dead at the age of 81. While Mauldin's entire body of work is impressive, it's his earliest work — the drawings of GIs Willie and Joe — that earned him the highest praise.

Mauldin made Willie and Joe the voice of the World War II infantryman. Published in Stars and Stripes and other military newspapers, they kept his fellow soldiers entertained and turned Mauldin into an icon. From 1940 to 1945, the unshaven, slump-shouldered soldiers mucked their way through Europe, surviving the enemy and the elements while mocking everything from their orders to their equipment. What endeared Mauldin to the soldiers is that he was one of them, spending most of his time with the 45th Division.

Many Americans remember Mauldin's cartoon in the Chicago Sun-Times, published after President Kennedy's assassination. It showed a grieving Abraham Lincoln, his hands covering his face, at the Lincoln Memorial. But it was because of Willie and Joe that he was remembered so fondly.

Almost every Veterans Day, the late Charles Schulz would honor Mauldin by having Snoopy, as the World War I flying ace, toast the cartoonist with a mug of root beer. Americans should give a similar toast to remember Mauldin and what he meant to a generation of soldiers.

Thursday, January 30, 2003

Cartoonist Mauldin is laid to rest at Arlington

By Patrick J. Dickson, Stars and Stripes

Pacific edition, Friday, January 31, 2003

WASHINGTON — Under skies as bleak as the battered Europe he once drew, former Stars and Stripes cartoonist Bill Mauldin was laid to rest Wednesday at Arlington National Cemetery.

Mauldin died at a California nursing home on January 23, 2003, after a long bout with Alzheimer’s. He was 81.

But it was his life that was remembered by Chaplain (Major) Douglas Fenton and about 50 mourners, mostly family, that gathered in a cold drizzle to pay their respects.

The chaplain listed war heroes and leaders buried at Arlington, then spoke of “the man we honor today, loved by the ‘greatest generation,’ a man who led hearts and warmed smiles” with his distinct talents.

Fenton mentioned one of the thousands of letters Mauldin received while in the nursing home, relaying that the soldier said Mauldin’s “humor kept them moving forward, even in the face of adversity.”

And with the Pentagon behind them in the distance, seven soldiers from the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment, The Old Guard, fired three volleys into the cold air for Mauldin, a Purple Heart recipient.

After Taps was played, Sergeant Major of the Army Jack Tilley took the flag from the honor guard and presented it to Sam Mauldin, the 16-year-old son of the Pulitzer Prize-winning artist.

One of Mauldin’s other sons, David, spoke after the ceremony. Before taking questions, he insisted that those who wrote to his father in the last months of his life be thanked.

“The family is so grateful to the soldiers and veterans who wrote to Dad at the nursing home to express their thoughts and feelings. It really made a difference to Dad.”

Though Alzheimer’s disease had begun to rob Mauldin of his faculties, he still understood the significance of the gestures.

“It’s hard not to understand, when boxes of letters and mementos come into your life, that you’re still important to people,” David said.

Newspaper columnist Bob Greene wrote in August that the cartoonist was in failing health, and provided an address where admirers could send their wishes. Asked how many letters his father had received, David paused.

“A couple of months ago, it went past 10,000,” he said.

The younger Mauldin noted, as did many at the brief ceremony, that the cold and drizzle was the perfect setting for his father’s funeral.

“It would make sense for him to die in the middle of winter, in terrible weather with lots of mud,” he said.

It was so dismal one had to wonder if Willie and Joe, his bleary-eyed protagonists in many a cartoon, were not there in spirit.

David Mauldin recalled a cartoon in which his father captured the camaraderie of soldiers at the front.

Sitting down in the reeds, their feet lost in the muck, Willie thanks his buddy with the best gift he could give, given the circumstances.

“Joe, yestiddy ya saved my life an’ I swore I’d pay ya back. Here’s my last pair of dry socks,” reads the caption.

“One person sent me a pair of socks,” David said. “A guy named Bill Ellis sent the socks after [Dad’s] death. That moved me to tears.”

And he started to cry.

- An honor guard from the Army's 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment carries Bill

Mauldin's casket to his grave Wednesday at Arlington National Cemetery.

- Sergeant First Class Michael Yoder, a bugler for the U.S. Army Band,

plays “Taps” at Bill Mauldin's funeral.

- The casket team folds the flag for

presentation to Bill Mauldin's family.

- Sergeant Major of the Army Jack Tilley presents the flag to

Bill Mauldin's 16-year-old son, Sam.

At right is Mauldin's former wife, Christine Lund.

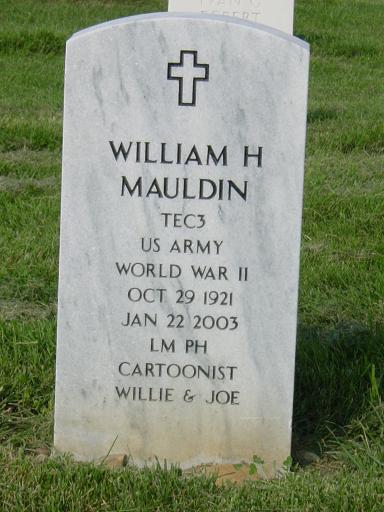

Bill Mauldin was laid to rest on 29 January 2003 in Arlington National Cemetery,

Section 64, Grave 6974. Accordingly, he is now at rest among his beloved GI's.

Arlington, Virginia – A cold and steady rain has been falling today for the burial of cartoonist Bill Mauldin at Arlington National Cemetery.Willie and Joe, Mauldin's perpetually cold and often wet World War Two infantrymen, would not have been surprised.

The fictional G-Is slogged their way through Europe, coping with mud and worse by poking fun at officers and idealistic enlisted men. Mauldin's edgy cartoons lifted the spirits of U-S soldiers around the world.

The winner of two Pulitzer Prizes died last week of complications from Alzheimer's disease. He was 81.

After the graveside service, son David Mauldin thanked all the vets who recently wrote to his father. The campaign was meant to spark Mauldin's failing memory through letters filled with war stories and words of thanks.

Mauldin received more than ten-thousand letters and parcels.

22 January 2003: WWII Cartoonist Bill Mauldin Dies at 81NEWPORT BEACH, California – Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist Bill Mauldin, who as a young Army rifleman during World War II gave newspaper readers back home a sardonic, foxhole-level view of the front with his drawings of weary, dogface GIs Willie and Joe, died Wednesday at 81.

Mauldin died at a nursing home of complications from Alzheimer's disease, including pneumonia, said Andy Mauldin, one of his seven sons.

“It's really good that he's not suffering anymore,” he said. “He had a terrible struggle.”

Mauldin was one of the pre-eminent editorial cartoonists of the 20th century, writing and drawing 16 books.

It was at the Chicago Sun-Times where Mauldin drew one of his most famous cartoons, published after President Kennedy's assassination. It showed a grieving Abraham Lincoln, his hands covering his face, at the Lincoln Memorial.

With Willie and Joe, Mauldin became the voice of the World War II infantryman. From 1940 to 1945, the laconic pair of unshaven, slump-shouldered soldiers slogged their way through battle-scarred Europe, surviving the enemy and the elements while sarcastically mocking everything from their orders to their equipment and even their allies.

In one drawing, soldiers are marching, bone-weary. Says Willie: “Maybe Joe needs a rest. He's talking in his sleep.”

In another, the two are about to jump a down-in-the-mouth German soldier walking by with a bottle of liquor. Willie says: “Don't startle ‘im, Joe. It's almost full.” And in another, Willie tells a medic: “Just gimme a coupla aspirin. I already got a Purple Heart.”

In yet another drawing, Willie grabs a weary GI by the collar and holds up a letter from home: “My son. Five days old. Good-lookin' kid, ain't he?”

The cartoons, published in Stars and Stripes and other military journals, delighted his fellow soldiers and endeared Mauldin to Americans at home.

“I wish we had more like him,” said syndicated cartoonist Paul Conrad (news), who served in the Pacific during World War II. “He would have been a lot of fun to go through the war with.”

In his book “Up Front,” Mauldin said the expressions on Joe and Willie are “those of infantry soldiers who have been in the war for a couple of years.”

“If he is looking very weary and resigned to the fact that he is probably going to die before it is over, and if he has a deep, almost hopeless desire to go home and forget it all; if he looks with dull, uncomprehending eyes at the fresh-faced kid who is talking about all the joys of battle and killing Germans, then he comes from the same infantry as Joe and Willie,” Mauldin wrote.

Mauldin called himself “as independent as a hog on ice,” and his nonconformist approach brought him a face-to-face upbraiding from Gen. George Patton. Mauldin continued to draw what he wanted.

In 1945, at age 23, his series “Up Front With Mauldin,” featuring Willie and Joe, won him the first of his two Pulitzers for editorial cartooning.

The second prize came in 1959, while he was at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, for depicting Soviet novelist Boris Pasternak saying to another gulag prisoner: “I won the Nobel Prize for literature. What was your crime?”

William Mauldin was born October 29, 1921, near Santa Fe, New Mexico, and spent much of his life in the West. He attended the Academy of Fine Art in Chicago, learning from such teachers as cartoonist Vaughn Shoemaker, a Pulitzer-winner for the Chicago Daily News.

Mauldin enlisted in 1940 and, assigned as a rifleman to the 180th Infantry, started drawing cartoons depicting training camp for the Division News, the newspaper for the 45th Division.

Once Mauldin's 45th Division shipped overseas, Stars and Stripes, the military-wide newspaper, began publishing his drawings. He was later assigned to Stars and Stripes but continued to spend most of his time with the 45th Division, where he said he received his inspiration.

Author and former Vietnam War correspondent David Halberstam wrote: “One senses that if a war reporter who had been with Hannibal or Napoleon saw Mauldin's work, he would know immediately that the work was right.”

After the war, Mauldin freelanced for a time. He joined the Post-Dispatch in 1958, then switched to the Sun-Times in 1962.

He also acted in two movies, including John Huston's 1951 production of “The Red Badge of Courage.”

In recent years, as Mauldin battled Alzheimer's, thousands of veterans, widows and other well-wishers sent him letters, offering thanks and stories of survival.

“You have managed to capture the irony, double standards and outright insanity of Army life,” one man wrote, “in a way that allows us to laugh at ourselves and our leaders and keep moving forward in the face of adversity.”

The campaign to recognize him was sparked by veteran Jay Gruenfeld, who spent years wondering what happened to the man who had made him laugh in a foxhole under fire. He sought out Mauldin and then wrote to veterans organizations and contacted newspaper columnists urging people to remember him. Soon Mauldin was receiving hundreds of letters a day.

Said Andy Mauldin: “They tried to pay him back for support he had given them.”

Mauldin is survived by former wives Jean Mauldin and Christine Lund and all of his sons. Funeral arrangements were incomplete, but burial is planned in Arlington National Cemetery.

Editorial cartoonist Bill Mauldin dies at 81Wednesday January 22, 2003

NEWPORT BEACH, California – Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist Bill Mauldin, who as a young Army rifleman during World War II gave newspaper readers back home a sardonic, foxhole-level view of the front with his drawings of weary, dogface GIs Willie and Joe, died Wednesday at 81.Mauldin died at a nursing home of complications from Alzheimer's disease, including pneumonia, said Andy Mauldin, one of his seven sons.

“It's really good that he's not suffering anymore,” he said. “He had a terrible struggle.”

Mauldin was one of the pre-eminent editorial cartoonists of the 20th century, writing and drawing 16 books.

It was at the Chicago Sun-Times where Mauldin drew one of his most famous cartoons, published after President Kennedy's assassination. It showed a grieving Abraham Lincoln, his hands covering his face, at the Lincoln Memorial.

With Willie and Joe, Mauldin became the voice of the World War II infantryman. From 1940 to 1945, the laconic pair of unshaven, slump-shouldered soldiers slogged their way through battle-scarred Europe, surviving the enemy and the elements while sarcastically mocking everything from their orders to their equipment and even their allies.

In one drawing, soldiers are marching, bone-weary. Says Willie: “Maybe Joe needs a rest. He's talking in his sleep.”

In another, the two are about to jump a down-in-the-mouth German soldier walking by with a bottle of liquor. Willie says: “Don't startle ‘in, Joe. It's almost full.” And in another, Willie tells a medic: “Just gimme a coupla aspirin. I already got a Purple Heart.”

In yet another drawing, Willie grabs a weary GI by the collar and holds up a letter from home: “My son. Five days old. Good-lookin' kid, ain't he?”

The cartoons, published in Stars and Stripes and other military journals, delighted his fellow soldiers and endeared Mauldin to Americans at home.

In his book “Up Front,” Mauldin said the expressions on Joe and Willie are “those of infantry soldiers who have been in the war for a couple of years.”

“If he is looking very weary and resigned to the fact that he is probably going to die before it is over, and if he has a deep, almost hopeless desire to go home and forget it all; if he looks with dull, uncomprehending eyes at the fresh-faced kid who is talking about all the joys of battle and killing Germans, then he comes from the same infantry as Joe and Willie,” Mauldin wrote.

Mauldin called himself “as independent as a hog on ice,” and his nonconformist approach brought him a face-to-face upbraiding from General George Patton. Mauldin continued to draw what he wanted.

In 1945, at age 23, his series “Up Front With Mauldin,” featuring Willie and Joe, won him the first of his two Pulitzers for editorial cartooning.

The second prize came in 1959, while he was at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, for depicting Soviet novelist Boris Pasternak saying to another gulag prisoner: “I won the Nobel Prize for literature. What was your crime?”

William Mauldin was born Oct. 29, 1921, near Santa Fe, N.M., and spent much of his life in the West. He attended the Academy of Fine Art in Chicago, learning from such teachers as cartoonist Vaughn Shoemaker, a Pulitzer-winner for the Chicago Daily News.

Mauldin enlisted in 1940 and, assigned as a rifleman to the 180th Infantry, started drawing cartoons depicting training camp for the Division News, the newspaper for the 45th Division.

Once Mauldin's 45th Division shipped overseas, Stars and Stripes, the military-wide newspaper, began publishing his drawings. He was later assigned to Stars and Stripes but continued to spend most of his time with the 45th Division, where he said he received his inspiration.

Author and former Vietnam War correspondent David Halberstam wrote: “One senses that if a war reporter who had been with Hannibal or Napoleon saw Mauldin's work, he would know immediately that the work was right.”

After the war, Mauldin freelanced for a time. He joined the Post-Dispatch in 1958, then switched to the Sun-Times in 1962.

He also acted in two movies, including John Huston's 1951 production of “The Red Badge of Courage.”

In recent years, as Mauldin battled Alzheimer's, thousands of veterans, widows and other well-wishers sent him letters, offering thanks and stories of survival.

“You have managed to capture the irony, double standards and outright insanity of Army life,” one man wrote, “in a way that allows us to laugh at ourselves and our leaders and keep moving forward in the face of adversity.”

The campaign to recognize him was sparked by veteran Jay Gruenfeld, who spent years wondering what happened to the man who had made him laugh in a foxhole under fire. He sought out Mauldin and then wrote to veterans organizations and contacted newspaper columnists urging people to remember him. Soon Mauldin was receiving hundreds of letters a day.

Said Andy Mauldin: “They tried to pay him back for support he had given them.”

Mauldin is survived by former wives Jean Mauldin and Christine Lund and all of his sons. Funeral arrangements were incomplete, but burial is planned in Arlington National Cemetery.

WWII cartoonist Bill Mauldin dies at 81

January 22, 2003NEWPORT BEACH, California — Bill Mauldin, the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist who portrayed World War II reality laced with humor, died today. He was 81.

Mauldin, one of the 20th century's pre-eminent editorial cartoonists, died of complications from Alzheimer's disease, including pneumonia, at a Newport Beach nursing home, said Andy Mauldin, 54, of Santa Fe, New Mexico, one of the cartoonist's seven sons.

‘It's really good that he's not suffering anymore,” he said. “He had a terrible struggle.”

His characters Willie and Joe, a laconic pair of unshaven, mud-encrusted dogfaces, slogged their way through Italy and other parts of battle-scarred Europe, surviving the enemy and the elements while caustically and sarcastically harpooning the unctuous and pompous.

They were the vessels that Mauldin, a young Army rifleman, filled with wry understatement to portray the tedium and treachery of war, entertaining and endearing himself to millions of fellow soldiers in the war and to Americans at home.

In his classic book “Up Front,” Mauldin wrote that the expressions on Joe and Willie are “those of infantry soldiers who have been in the war for a couple of years.”

“If he is looking very weary and resigned to the fact that he is probably going to die before it is over, and if he has a deep, almost hopeless desire to go home and forget it all; if he looks with dull, uncomprehending eyes at the fresh-faced kid who is talking about all the joys of battle and killing Germans, then he comes from the same infantry as Joe and Willie,” he wrote.

Mauldin called himself “as independent as a hog on ice,” and his nonconformist approach brought him a face-to-face upbraiding from Gen. George Patton. Mauldin continued to draw what he wanted.

In 1945, at age 23, his series “Up Front With Mauldin” won him the first of his two Pulitzer Prizes for editorial cartooning.

Mauldin won the second in 1959, while he was an editorial cartoonist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, for depicting Soviet novelist Boris Pasternak saying to another gulag prisoner: “I won the Nobel Prize for literature. What was your crime?

Mauldin wrote and drew 16 books and acted in two movies, including John Huston's 1951 production of “The Red Badge of Courage” starring real-life war hero Audie Murphy.

Mauldin was born near Santa Fe, New Mexico, and spent much of his life in the West. A teacher in high school helped him nurture his art talent, and he attended the Academy of Fine Art in Chicago, learning from such teachers as cartoonist Vaughn Shoemaker, a Pulitzer Prize-winner for the Chicago Daily News.

Mauldin enlisted in 1940 and, assigned as a rifleman to the 180th Infantry, started drawing cartoons depicting training camp for the Division News, the newspaper for the 45th Division.

Once Mauldin's 45th Division shipped overseas, Stars and Stripes, the servicewide newspaper, began publishing his drawings.

Author David Halberstam wrote: “One senses that if a war reporter who had been with Hannibal or Napoleon saw Mauldin's work he would know immediately that the work was right.”

After the war, Mauldin free-lanced for a time. He joined the Post-Dispatch in 1958, then switched to the Chicago Sun-Times in 1962.

It was at the Sun-Times that he drew one of his most poignant and famous cartoons on the day of President John F. Kennedy's assassination. The drawing showed a grieving Abraham Lincoln, his hands covering his face, at the Lincoln Memorial.

In recent years, as Mauldin battled Alzheimer's, thousands of veterans, widows and other well-wishers have sent him letters, offering thanks and stories of survival.

“You have managed to capture the irony, double standards and outright insanity of Army life,” one man wrote, “in a way that allows us to laugh at ourselves and our leaders and keep moving forward in the face of adversity.”

The campaign to recognize him was sparked by veteran Jay Gruenfeld, who spent years wondering what happened to the man who had made him laugh in a foxhole under fire. He sought out Mauldin and then wrote to veterans organizations and contacted newspaper columnists urging people to remember him.

Bill Mauldin, Newspaper Cartoonist, Dies at 81

By RICHARD SEVEROBill Mauldin, the Army Sergeant who created Willie and Joe, the cartoon characters who became enduring symbols of the grimy, irrespressible American infantrymen who triumphed over the German army and prevailed over their own rear-echelon officers in World War II, died today in Newport Beach, Calif. He was 81 years old.

After Willie and Joe won the war, Mr. Mauldin became a syndicated newspaper cartoonist and went on for more than 50 years to caricature bigots, superpatriots, doctrinaire liberals and conservatives and pompous souls in whatever form they appeared. He twice won the Pulitzer Prize, one in 1944 for his World War II work, the other in 1959 for his commentary on Soviet treatment of Boris Pasternak.

Andy Mauldin, one of the cartoonist's seven sons, told The Associated Press that his father died of complications from Alzheimer's disease, including pneumonia, at a Newport Beach nursing home.

Mr. Mauldin gave up regular cartooning assignments in the early 1990's, complaining that arthritis made it too difficult for him to draw. He made his retirement home in his native New Mexico.

He frequently lamented that editorial cartoonists were too soft and that more of them needed to be “stirrer-uppers.” Mr. Mauldin worked full-time at being a stirrer-upper and while he was on duty, nobody was safe from his editorial brush. During the war, he excoriated self-important generals, grassy green 90-day wonders, insensitive drill sergeants, palate-dulled mess sergeants, glamour-dripping Air Force pilots in leather jackets, and cafe owners in liberated countries who rewarded the thirsty GIs who had freed them by charging them double for brandy. He was nothing short of beloved by his fellow enlisted men.

But no Mauldin characters were more memorable than Willie and Joe, the unshaven, listless, dull-eyed, cynical dogfaces who spent the war fighting the Germans, trying to keep dry and warm and flirting with insubordination. They were the stars of “Up Front,” Mr. Mauldin's wartime best seller, and their exploits were reported regularly in various service publications, including Stars and Stripes and the 45th Division News. Their likenesses were found in pup tents and bivouacs from Brittany to Berlin, tacked up next to the inevitable glossies of those other G.I. favorites, Betty Grable and Dorothy Lamour.

Willie and Joe were the guys who always got sentry duty when it rained or snowed and shrapnel in their backsides whenever they left their foxholes. It was they who contended with lice and fleas, complained constantly about the K-rations they were supposed to eat, drank grappa and other strong brews made from suspicious ingredients, slept in rat-infested barns, never seemed to find the soap when they had the rare opportunity to bathe in a cold river, and suffered the incessant, grinding, morale-destroying boredom that only the infantry soldier knows.

The only thing that could never be questioned about Willie and Joe was their determination to survive and to win.

Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme allied commander, looked forward to their adventures and General Mark Clark so appreciated them that he saw to it that Mr. Mauldin got a specially equipped Jeep in Italy so that he could go where he wanted and draw what he wished. Ernie Pyle, whom the GIs probably respected over all other correspondents, termed Mr. Mauldin the best cartoonist of the war because he drew pictures of the men who were “doing the dying,” even though nobody could ever kill Willie and Joe.

General George S. Patton was one of a small minority who had no use for them. He liked his heroes clean-shaven and obedient and he was uneasy that the men who served under him revered the likes of such unorthodoxy. Asked toward the end of the war to comment on Sergeant Mauldin's cartoons, General Patton replied, “I've seen only two of them and I thought they were lousy.”

At one point, Sergeant Mauldin visited General Patton and they discussed the cartoons. Mr. Mauldin ended the meeting by saying he was sure the general did not want him to represent the American soldier in a less than realistic way.

Mr. Mauldin's representations have endured in unforgettable images and words:

“Just gimme a coupla aspirin. I already got a Purple Heart,” says a weary Joe to a corpsman seated at a table containing medicine and medals,

“He's right Joe,” says Willie after a superior admonishes them for the slovenly way they look. “When we ain't fightin' we should ackt more like sojers.”

“Must be a tough objective,”says Willie to Joe as they huddle on the side of a road, weapons ready.”Th' old man says we're gonna have th' honor of liberatin' it.”

“Beautiful view,”says Joe to Willie as they watch a beautiful sunset from the top of a mountain.”Is there one for enlisted men?”

“Oh, I likes officers. They make me want to live till the war's over,” Joe assures Willie as they lug their gear to another battlefield.

Joe was created first by Mr. Mauldin, well before Pearl Harbor. Joe was never an angel but at least he was a clean-shaven, well-scrubbed young man and he appeared in various Army publications, especially the 45th Division News. After Dec. 7, 1941 he met Willie and the two went through the Italian campaign together, becoming quite disreputable in their personal habits.

Willie and Joe and their creator made the cover of Time magazine in 1945 —the year after won his first Pulitzer — and he came home from the war a celebrity. He had made a lot of money but wasn't very happy. “I never quite could shake off the guilt feeling that I had made something good out of the war,” he said.

After the war, Mr. Mauldin seemed lost for a time. He covered the Korean War briefly for Collier's but was not entirely pleased with his work. He resuscitated Joe, made him a war correspondent, and had him writing pearls of wisdom in letters to the stateside Willie. In 1958, he visited Dan Fitzpatrick, editorial cartoonist for The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, who disclosed that he was planning to retire. Mr. Mauldin applied for the job, got it, and won a second Pulitzer Prize in 1959 on the plight of the Russian author Boris Pasternak. The cartoon showed two prisoners in Siberia, one of whom said to the other, “I won the Nobel Prize for Literature. What was your crime?”

Mr. Mauldin remained with the Post-Dispatch until 1962, when he joined the Chicago Sun-Times. He seemed to regain his old form and was for years regarded as one of the most influential cartoonists of his day.

`If I see a stuffed shirt, I want to punch it,” Mr. Mauldin once said. “If its big, hit it. You can't go far wrong.”

From his point of view, too many newspaper artists tended to “regard editorial cartooning as a trade instead of a profession. They try not to be too offensive. The hell with that.”

Mr. Mauldin delighted in his jousts against Senators John E. Stennis and Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi, a couple of Democrats who preached the virtues of segregation; Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy, the Republican from Wisconsin who saw communists and their sympathizers seemingly everywhere; General Francisco Franco of Spain for his oligarchical oppression; Charles de Gaulle for his expansive dreams of French destiny, and Soviet Premier Nikita S. Khrushchev for his bluster.

Mr. Mauldin used his pen to strike at the Ku Klux Klan and veterans' organizations that he thought were too far to the right. He later said he thought he had gone too far in his denunciations and “became a bore.” Many newspapers agreed and began to drop his syndicated cartoons.

He became an advocate for veterans and joined the American Veterans Committee, which saw itself as an alternative to more traditional organizations like the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars. He served two terms as its president in the 1950's.

Mr. Mauldin did not confine his activities to drawing. His postwar book “Back Home” was as much as job of writing as it was drawing and it got good reviews on both counts. He also appeared in movies.

John Huston wanted to make a film of Stephen Crane's classic novel of the Civil War, “The Red Badge of Courage.” But he had to persuade Louis B. Mayer and the executives of MGM, who opposed the film because they didn't think the public would support a movie about a youth who runs away from his first battle and then returns to the front and his comrades and performs several acts of heroism; after all, there was no standard plot, no romance, no leading ladies. Mr. Huston got the film made in 1951 after he hit on the idea of casting two icons of the second world war in the lead roles: Audie Murphy, the most decorated hero of the war, as the Youth, and Bill Mauldin as his friend, the Loud Soldier.

Mr. Murphy and Mr. Mauldin earned good reviews for their performances but the movie failed at the box office and fell short of Mr. Huston's dream of creating a classic. It did achieve a life, however, when its troubled production became the subject of Lillian Ross book “Picture,” which endures as a major book about Hollywood.

Mr. Mauldin also earned good notices for his role in Fred Zinnemann's 1951 movie “Teresa,” but he did not like Hollywood. “Movie acting is like driving a locomotive,” he declared. “Its one of those things you want to do once in your life and once is enough.” He said that as it was in the army, “all you do in Hollywood is hurry up and wait.”

In the middle 1950's he moved to Rockland County in New York and in 1956 decided to run for Congress against the incumbent conservative Republican Katharine St. George in the 28th District. Mr. Mauldin thought of himself as a left of center candidate. Mrs. St. George, a first cousin of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, leaned toward the philosophy of her grandfather, Warren Delano, who had told her, “I will not say that all Democrats are horse thieves but it would seem that all horse thieves are Democrats.” She defeated Mr. Mauldin easily to win a sixth term.

William Henry Mauldin was born October 29, 1921 in Mountain Park, New Mexico, one of two sons born to Sidney Albert Mauldin, a handyman, and Edith Katrina Bemis Mauldin. As a child, he suffered from rickets, a disease caused by a deficiency of vitamin D, and was unable to engage in strenuous activity. His head seemed too big for his spindly body. When he was 8 years old, he heard one of his father's friends say, “If that was my son, I'd drown him.”

Mr. Mauldin never forgot the insult and turned all his energy to teaching himself how to draw. His family moved to Phoenix and while he was still in high school there, he enrolled in a correspondence cartoon school.

He left high school without getting a diploma, moved to Chicago, and continued his studies at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. His maternal grandmother gave him the the $300 tuition fee.

He moved back to Phoenix and began to sell his drawings. Among the first were published by “Arizona Highways” magazine. In 1940, Mr. Mauldin also created cartoons for both sides in the Texas gubernatorial campaign. He later said he joined the Arizona National Guard to avoid the Texas politicians, who discovered he was working both sides of the fence. The Guard required no physical examination — Mr. Mauldin doubted he could ever pass one — and he was accepted. When the Arizona Guard was federalized in 1940, Mr. Mauldin found himself in the Army some 18 months before Pearl Harbor was attacked.

He scored more than 140 on his Army I.Q. test and later said that once the Army became aware of this, it did with him what it tended to do with all bright people who become enlisted men. It gave him K.P. for four months.

He managed to get a transfer to Oklahoma's 45th Division so that he could draw cartoons for the 45th Division News, first as a volunteer, later as a member of the staff.

He had two war experiences after Korea. One came in 1965 when he visited his son, Bruce, a serviceman stationed in Vietnam. Mr. Mauldin wrote about an attack on Pleiku. He also visited troops in Saudi Arabia during the Persian Gulf war in 1991, toward the end of his career. He did not approve of the war and his cartoons were especially hard on President George Bush. He made no further use of Willie and Joe.

“Up Front” was republished in a 50th anniversary edition in 1995 Among Mr. Mauldin's other books were “A Sort of a Saga,” 1949; “Bill Mauldin's Army,” 1951; “Bill Mauldin in Korea,” 1953; “What's Got Your Back Up,” 1961; “I've Decided I Want My Seat Back,” 1965; and “The Brass Ring,” 1972. He also illustrated many articles for Life magazine, The Saturday Evening Post, Sports Illustrated and other publications.

Mr. Mauldin married Norma Jean Humphries in 1942. They had two sons, Bruce and Timothy. They were divorced in 1946. The following year he married Natalie Sarah Evans. They had four sons, Andrew, David, John and Nathaniel. She died in a car accident. In 1972, he married Christine Lund. They had a daughter, Kaja.

Posted on Friday, October 7, 2005

Late cartoonist an inspiration to young artist

Zachary Waters and the other fifth-graders at Springdale Elementary will travel to Washington, D.C., on their class trip in the spring. His mother, Sherry, hopes to go along as a chaperone.

On their sightseeing wish list is Arlington National Cemetery. But Zachary and Sherry won't be nearly as interested in visiting the graves of former presidents and military heroes as they will be paying their respects in Section 64 to Grave 6974.

That's where Bill Mauldin was buried on a cold, drizzly January day two years ago.

Although the famous World War II cartoonist died before the mother and son became familiar with his work, he has had a major influence on young Zachary's life.

“If he were alive today, I would try to meet him and thank him,” said Sherry. “I would ask for his autograph. The way he personified the war has inspired a 10-year-old to start drawing. And that's a good thing.”

Sherry is a single parent, and Zachary is her only child. They moved to Macon two years ago.

While other children his age are more likely to gravitate toward Star Wars and Harry Potter, Zachary has developed a special interest.

He has become somewhat of an authority on World War II. He made a “100” on a school report he did on Mauldin earlier this week.

“I'm addicted to learning everything I can about World War II,” said Zachary.

What pricked this curiosity was discovering the works of Mauldin, who made his primary characters, Willie and Joe, a mouthpiece for American soldiers.

Just as journalist Ernie Pyle was on the front lines reporting on the war, Mauldin was in the trenches putting a human face on the conflict with his drawings of stoop-shouldered and scruffy-faced soldiers.

He twice won the Pulitzer Prize (1945 and '59), wrote 16 books and had his cartoons syndicated in more than 250 newspapers.

He also was famous for a cartoon published in The Chicago Sun-Times depicting a grieving Abraham Lincoln with his hands covering his face following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. On Veteran's Day, the late Charles Schulz often would have Snoopy, dressed as the World War I flying ace, honor Mauldin by toasting him with a mug of root beer.

Zachary might be the youngest unofficial member of the Bill Mauldin fan club.

He and his mother went to the library and checked out every Mauldin book they could find. Soon, Zachary was emulating Mauldin's cartoons.

“I gave him some art supplies and drawing pads,” Sherry said. “I was amazed at how good his drawings were. I asked him if he had traced them, and he hadn't. They were all freehand.”

He copied almost every picture in Mauldin's famous book “Up Front.” He was so observant of every detail, he even noticed in one cartoon there were too many hands for the number of soldiers pictured.

Of course, this delighted Sherry, since she is a color imaging specialist with Macon Prints & Instruments.

Looks like Zachary might be a drop off the old palette.

Yes, Zachary might grow up to become an artist or historian. But, even if he doesn't, Mauldin would have been proud to know how much he inspired a child to think and to create.

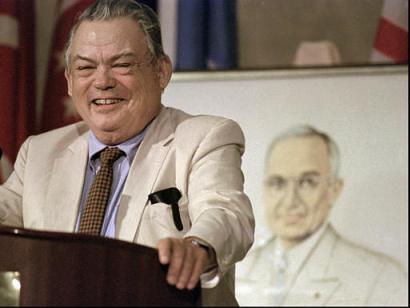

- Cartoonist Bill Mauldin smiles after receiving the Harry S. Truman Good Neighbor Award in this May 8, 1996, file photo, in Kansas City, Mo. Mauldin, one of the 20th century's pre-eminent editorial cartoonists, died of complications from Alzheimer's disease (news – web sites), at a Newport Beach, Calif., nursing home, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2003. He was 81.

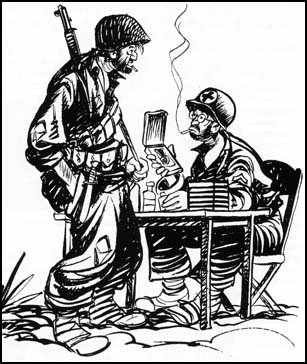

- Private Robert L. Bowman, left, of Hogansville, Georgia, poses for Stars and Stripes artist Sergeant Bill Mauldin, on the Anzio beachhead in Italy during World War II in May, 1944. The completed picture will be known as “G.I. Joe.”

- This cartoon featuring the weary, dogface GIs ‘Willie and Joe,' was created by Sergeant Bill Mauldin of United Feature Syndicate, Inc., who as a young Army rifleman during World War II gave newspaper readers back home a sardonic, foxhole-level view of the front. Mauldin, the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist who portrayed World War II reality laced with humor, died Wednesday, January 22, 2003, in Newport Beach, California. He was 81

- “Just give me the aspirin. I already got a Purple Heart.”

MAULDIN, WILLIAM HENRY

- TEC3 US ARMY

- WORLD WAR II

- DATE OF BIRTH: 10/29/1921

- DATE OF DEATH: 01/22/2003

- BURIED AT: SECTION 64 SITE 6874

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard