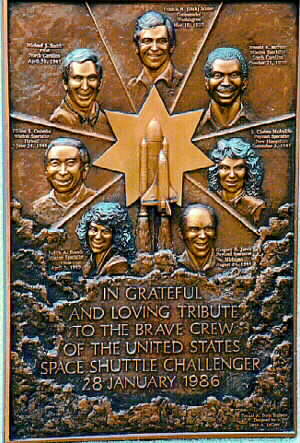

At about 11:30 AM, Eastern Time, January 28, 1986, the Shuttle Challenger was launched from Cape Kennedy, Florida. Aboard the ship were its Commander, Francis R. “Dick” Scobee, its pilot, Michael J. Smith, and its crew, Christa McAuliffe (the first ‘Teacher in Space'), Mission Specialists Ellison S. Onizuka, Judith A. Resnick and Ronald E. McNair, along with Payload Specialist Gregory B. Jarvis.

Seventy-three seconds into the mission, the Challenger exploded and fell into the sea. On April 29, 1986 the identified remains that had been located were turned over to their families for burial. However, there were number of unidentified remains. These remains were buried at Arlington National Cemetery on May 20, 1986, beneath the Memorial that appears below. Two of the crewmembers, Scobee and Smith, were buried in Arlington National Cemetery as well.

President Reagan's Speech on The Challenger Disaster

Ronald Reagan — Oval Office of the White House, January 28, 1986

Nineteen years ago, almost to the day, we lost three astronauts in a terrible accident on the ground. But, we've never lost an astronaut in flight; we've never had a tragedy like this. And perhaps we've forgotten the courage it took for the crew of the shuttle; but they, the Challenger Seven, were aware of the dangers, but overcame them and did their jobs brilliantly. We mourn seven heroes: Michael Smith, Dick Scobee, Judith Resnik, Ronald McNair, Ellison Onizuka, Gregory Jarvis, and Christa McAuliffe. We mourn their loss as a nation together.

For the families of the seven, we cannot bear, as you do, the full impact of this tragedy. But we feel the loss, and we're thinking about you so very much. Your loved ones were daring and brave, and they had that special grace, that special spirit that says, ‘Give me a challenge and I'll meet it with joy.' They had a hunger to explore the universe and discover its truths. They wished to serve, and they did. They served all of us.

We've grown used to wonders in this century. It's hard to dazzle us. But for twenty-five years the United States space program has been doing just that. We've grown used to the idea of space, and perhaps we forget that we've only just begun. We're still pioneers. They, the members of the Challenger crew, were pioneers.

And I want to say something to the schoolchildren of America who were watching the live coverage of the shuttle's takeoff. I know it is hard to understand, but sometimes painful things like this happen. It's all part of the process of exploration and discovery. It's all part of taking a chance and expanding man's horizons. The future doesn't belong to the fainthearted; it belongs to the brave. The Challenger crew was pulling us into the future, and we'll continue to follow them…

There's a coincidence today. On this day 390 years ago, the great explorer Sir Francis Drake died aboard ship off the coast of Panama. In his lifetime the great frontiers were the oceans, and a historian later said, ‘He lived by the sea, died on it, and was buried in it.' Well, today we can say of the Challenger crew: Their dedication was, like Drake's, complete.

The crew of the space shuttle Challenger honoured us by the manner in which they lived their lives. We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for the journey and waved goodbye and ‘slipped the surly bonds of earth' to ‘touch the face of God.'

The Shuttle Explodes

6 IN CREW AND HIGH-SCHOOL TEACHER

ARE KILLED 74 SECONDS AFTER LIFTOFF

Thousands Watch Rain of Debris

By William J. Broad

Special to The New York Times

Cape Canaveral, Fla. Jan. 28, 1986 — The space shuttle Challenger exploded in a ball of fire shortly after it left the launching pad today, and all seven astronauts on board were lost.

The worst accident in the history of the American space program, it was witnessed by

thousands of spectators who watched in wonder, then horror, as the ship blew apart high in the air.

Flaming debris rained down on the Atlantic Ocean for an hour after the explosion, which occurred just after 11:39 A. M. It kept rescue teams from reaching the area where the craft would have fallen into the sea, about 18 miles offshore.

It seemed impossible that anyone could have lived through the terrific explosion 10 miles in the sky, and officials said this afternoon that there was no evidence to indicate that the five men and two women aboard had survived.

No Ideas Yet as to Cause

There were no clues to the cause of the accident. The space agency offered no immediate explanations, and said it was suspending all shuttle flights indefinitely while it conducted an inquiry. Officials discounted speculation that cold weather at Cape Canaveral or an accident several days ago that slightly damaged insulation on the external fuel tank might have been a factor.

Americans who had grown used to the idea of men and women soaring into space reacted with shock to the disaster, the first time United States astronauts had died in flight. President Reagan canceled the State of the Union Message that had been scheduled for tonight, expressing sympathy for the families of the crew but vowing that the nation's exploration of space would continue.

Killed in the explosion were the mission commander, Francis R. (Dick) Scobee; the pilot Comander Michael J. Smith of the Navy; Dr. Judith A. Resnik; Dr. Ronald E. McNair; Lieut. Col. Ellison S. Onizuka of the Air Force; Gregory B. Jarvis, and Christa McAuliffe.

Mrs. McAuliffe, a high-school teacher from Concord, New Hampshire, was to have

been the first ordinary citizen in space.

After a Minute, Fire and Smoke The Challenger lifted off flawlessly this morning, after

three days of delays, for what was to have been the 25th mission of the reusable shuttle fleet that was intended to make space travel commonplace. The ship rose for about a minute on a column of smoke and fire from its five engines.

Suddenly, without warning, it erupted in a ball of flame.

The shuttle was about 10 miles above the earth, in the critical seconds when the two solid-fuel rocket boosters are firing as well as the shuttle's main engines. There was some discrepancy about the exact time of the blast: The National Aeronautics and Space Administration said they lost radio contact with the craft 74 seconds into the flight, plus or minus five seconds.

Two large white streamers raced away from the blast, followed by a rain of debris that etched white contrails in the cloudless sky and then slowly headed toward the cold waters of the nearby Atlantic.

The eerie beauty of the orange fireball and billowing white trails against the blue confused many onlookers, many of whom did not at first seem aware that the aerial display was a sign that something had gone terribly wrong.

There were few sobs, moans or shouts among the thousands of tourists, reporters, and space agency officials gathered on an unusually cold Florida day to celebrate the liftoff, just a stunned silence as they began to realize that the Challenger had vanished.

Among the people watching were Mrs. McAuliffe's two children, her husband and her parents and hundreds of students, teachers and friends from Concord.

“Things started flying around and spinning around and I heard some oh's and ah's, and at that moment I knew something was wrong,” said Brian Ballard, the editor of The Crimson Review at Concord High School.

“I felt sick to my stomach. I still feel sick to my stomach.”

Ships Searching the Area

At an outdoor news conference held here this afternoon, Jesse W. Moore, the head of the shuttle program at NASA, said: “I regret to report that, based on very preliminary

searches of the ocean where the Challenger impacted this morning, these searches have not revealed any evidence that the crew of the Challenger survived.” Behind him, in the distance, the American flag waved at half-staff.

Coast Guard ships were in the area of impact tonight and planned to stay all night, with airplanes set to comb the area at first light for debris that could provide the clues to the catastrophe. Some material from the shattered craft was reported to be washing ashore on Florida beaches tonight, mostly the small heat-shielding tiles that protect the shuttle as it passes through the earth's atmosphere.

Films of the explosion showed a parachute drifting toward the sea, apparently one that would have lowered one of the huge reusable booster rockets after its fuel was spent.

Pending an investigation, Mr. Moore said at the news conference this afternoon, hardware, photographs, computer tapes, ground support equipment and notes taken by members of the launching team would be impounded.

The three days of delays and a tight annual launching schedule did not force a premature launching, Mr. Moore said in answer to a reporter's question.

‘Flight Safety a Top Priority'

“There was no pressure to get this particular launch up,” he said. “We have always maintained that flight safety was a top priority in the program.”

Several hours after the accident, Mr. Moore announced the appointment of an interim review team, assigned to preserve and identify flight data from the mission, pending the appointment of a formal investigating committee.

The members of the interim panel are Richard G. Smith, the director of the Kennedy Space Center; Arnold Aldridge, the manager of the National Space Transportation System, Johnson Space Center; William Lucas, director of the Marshall Space Flight Center; Walt Williams, a NASA consultant, and James C. Harrington, the director of Spacelab, who will serve as executive secretary.

A NASA spokesman said a formal panel could be appointed as soon as Wednesday by Dr. William R. Graham, the director of the space agency.

All American manned space launchings were stopped for more than a year and a half after the worst previous American space accident, in January 1967, when three astronauts were killed in a fire in an Apollo capsule on the launching pad.

‘Hope We Go Today'

This year's schedule was to have been the most ambitious in the history of the shuttle program, with 15 flights planned. For the Challenger, the workhorse of the nation's shuttle fleet, this was to have been the 10th mission.

Today's launching had been delayed three times in three days by bad weather. The Challenger was to have launched two satellites and Mrs. McAullife was to have broadcast two lessons from space to millions of students around the country.

All day long, well after the explosion, the large mission clocks scattered about the Kennedy Space Center continued to run ticking off the minutes and seconds of a flight that had long ago ended.

Long before liftoff this morning, skies over the Kennedy Space Center were clear and cold, reporters and tourists shivering in leather gloves, knit hats and down coats as temperatures hovered in the low 20's.

Icicles formed as ground equipment sprayed water on the launching pad, a precaution against fire.

At 9:07 A. M., after the astronauts were seated in the shuttle, wearing gloves because the interior was so cold, ground controllers broke into a round of applause as the shuttle's door, whose handle caused problems yesterday, which was closed.

“Good morning, Christa, hope we go today,” said ground control as the New Hampshire school teacher settled into the spaceplane.

“Good morning,” she replied, “I hope so, too.” Those are her last known words.

The liftoff, originally scheduled for a 9:38 A. M., was delayed two hours by problems on the ground caused first by a failed fire-protection device and then by ice on the shuttle's ground support structure.

The launching was the first from pad 39-B, which had recently undergone a $150 million overhaul. It had last been used for a manned launching in the 1970's.

Just before liftoff, Challenger's external fuel tank held 500,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen and oxygen, which are kept separate because they are highly volatile when mixed. The fuel is used in the shuttle's three main engines.

At 11:38 A. M. the shuttle rose gracefully off the launching pad, heading in to the sky. The shuttle's main engines, after being cut back slightly just after liftoff, a normal procedure, were pushed ahead to full power as the shuttle approached maximum dynamic pressure when it broke through the sound barrier.

“Challenger, go with throttle up,” said James D. Wetherbee of mission control in Houston about 11:39 A. M.

“Roger,” replied the commander, Mr. Scobee, “go with throttle up.”

Those were the last words to be heard on the ground from the winged spaceplane and her crew of seven.

As the explosion occurred, Stephen A. Nesbitt of Mission Control in Houston, apparently looking at his notes and not the explosion on his television monitor, noted that the shuttle's velocity was “2,900 feet per second, altitude 9 nautical miles, downrange distance 7 nautical miles.” That is a speed of about 1,977 miles an hour, a height of about 10 statute miles and a distance down range of about 8 miles.

The first official word of the disaster came from Mr. Nesbitt of Mission Control, who reported, “a major malfunction.” He added that communications with the ship had failed 1 minute 14 seconds into the flight.

“We have no downlink,” he said, referring to communications from the Challenger. “We have a report from the flight dynamics officer that the vehicle has exploded.”

His voice cracked. “The flight director confirms that,” he continued. “We're checking with the recovery forces to see what can be done at this point.”

Tapes Showed Small Fire

In the sky above the Kennedy Space Center, the shuttle's two solid-fuel rocket boosters sailed into the distance.

The explosion, later viewed in slow-motion televised replays taken by cameras equipped with telescopic lenses, showed what appeared to be the start of a small fire at the base of the huge external fuel tank, followed by the quick separation of the solid rockets. A huge fireball then engulfed the shuttle as the external tank exploded.

At the news conference, Mr. Moore would not speculate on the cause of the disaster.

The estimated pint of impact for debris was 18 to 20 miles off the Florida coast, according to space agency officials.

“The search and rescue teams were delayed getting into the area because of debris continuing to fall from very high altitudes, for almost an hour after ascent,” said Mr. Nesbitt of Mission Control in Houston.

Speaking at 1 P. M. in Florida, Lieut. Col. Robert W. Nicholson Jr., a spokesman for the rescue operation, which is run by the Defense Department, said range safety radars near the Kennedy Space Center detected debris falling for nearly an hour after the

explosion. “Anything that went into the area would have been endangered,” he

said in an interview.

In addition, the explosion of the huge fuel supply would have created a cloud of toxic vapors. NASA officials said tonight that the hazardous gases presented no danger to land, but the Coast Guard was advising boats and ships to avoid the area.

Not a Good Ditcher

In an interview last year, Tommy Holloway, the chief of the flight director office at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, talked about the possibility of a shuttle crash at sea.

“This airplane is not a good ditcher,” he said: “It will float O.K. if it doesn't break apart, and we have hatches we can blow off the top. But the orbiter lands fast, at 190 knots. You come in and stop in 100 yards or so. You decelerate like gangbusters, and anything in the payload bay comes forward. We don't expect a very good day if it comes to that.”

On board Challenger was the world's privately owned communication satellite, the $100 million Tracking and Data Relay Satellite, which with its rocket boosters weighed 37,636 pounds.

This morning, water froze on the shuttle service structure, used for fire fighting equipment and for emergency showers that technicians would use if they were exposed to fuel. The takeoff was delayed because space agency officials feared that during the first critical seconds of launching, icicles might fly off the service structure and damage the delicate heat-resistant tiles on the shuttle, which are crucial for the vehicle's re-entry through the earth's atmosphere.

National Aeronautics and

Space Administration

Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center

Houston, Texas

77058

RADM Richard H. Truly

Associate Administrator for Space Flight

NASA Headquarters

Code M

Washington, DC 20546

Dear Admiral Truly:

The search for wreckage of the Challenger crew cabin has been completed. A team of engineers and scientists has analyzed the wreckage and all other available evidence in an attempt to determine the cause of death of the Challenger crew. This letter is to report to you on the results of this effort.

The findings are inconclusive. The impact of the crew compartment with the ocean surface was so violent that evidence of damage occurring in the seconds which followed the explosion was masked. Our final conclusions are:

–the cause of death of the Challenger astronauts cannot be positively determined;

–the forces to which the crew were exposed during Orbiter breakup were probably not sufficient to cause death or serious injury; and

–the crew possibly, but not certainly, lost consciousness in the seconds following Orbiter breakup due to in-flight loss of crew module pressure.

Our inspection and analyses revealed certain facts which support the above conclusions, and these are related below:

The forces on the Orbiter at breakup were probably too low to cause death or serious injury to the crew but were sufficient to separate the crew compartment from the forward fuselage, cargo bay, nose cone, and forward reaction control compartment. The forces applied to the Orbiter to cause such destruction clearly

exceed its design limits.

The data available to estimate the magnitude and direction of these forces included ground photographs and measurements from

onboard accelerometers, which were lost two-tenths of a second after vehicle breakup.

Two independent assessments of these data produced very similar estimates. The largest acceleration pulse occurred as the Orbiter forward fuselage separated and was rapidly pushed away from the external tank. It then pitched nose-down and was decelerated rapidly by aerodynamic forces. There are

uncertainties in our analysis; the actual breakup is not visible on photographs because the Orbiter was hidden by the gaseous cloud surrounding the external tank. The range of most probable maximum accelerations is from 12 to 20 G's in the vertical axis. These accelerations were quite brief. In two seconds, they were

below four G's; in less than ten seconds, the crew compartment was essentially in free fall. Medical analysis indicates that these accelerations are survivable, and that the probability of major injury to crew members is low.

After vehicle breakup, the crew compartment continued its upward trajectory, peaking at an altitude of 65,000 feet approximately 25 seconds after breakup. It then descended striking the ocean surface about two minutes and forty-five seconds after breakup at a velocity of about 207 miles per hour. The forces imposed by

this impact approximated 200 G's, far in excess of the structural limits of the crew compartment or crew survivability levels.

The separation of the crew compartment deprived the crew of Orbiter-supplied oxygen, except for a few seconds supply in the lines. Each crew member's helmet was also connected to a personal egress air pack (PEAP) containing an emergency supply of breathing air (not oxygen) for ground egress emergencies, which

must be manually activated to be available. Four PEAP's were recovered, and there is evidence that three had been activated. The nonactivated PEAP was identified as the Commander's, one of the others as the Pilot's, and the remaining ones could not be associated with any crew member. The evidence indicates that the

PEAP's were not activated due to water impact.

It is possible, but not certain, that the crew lost consciousness due to an in-flight loss of crew module pressure. Data to support this is:

–The accident happened at 48,000 feet, and the crew cabin was at that altitude or higher for almost a minute. At that altitude, without an oxygen supply, loss of cabin pressure would have caused rapid loss of consciousness and it would not have been regained before water impact.

–PEAP activation could have been an instinctive response to unexpected loss of cabin pressure.

–If a leak developed in the crew compartment as a result of structural damage during or after breakup (even if the PEAP's had been activated), the breathing air available would not have prevented rapid loss of consciousness.

–The crew seats and restraint harnesses showed patterns of failure which demonstrates that all the seats were in place and occupied at water impact with all harnesses locked. This would likely be the case had rapid loss of consciousness occurred, but it does not constitute proof.

Much of our effort was expended attempting to determine whether a loss of cabin pressure occurred. We examined the wreckage carefully, including the crew module attach points to the fuselage, the crew seats, the pressure shell, the flight deck and middeck floors, and feedthroughs for electrical and plumbing

connections. The windows were examined and fragments of glass analyzed chemically and microscopically. Some items of equipment stowed in lockers showed damage that might have occurred due to decompression; we experimentally decompressed similar items without conclusive results.

Impact damage to the windows was so extreme that the presence or absence of in-flight breakage could not be determined. The estimated breakup forces would not in themselves have broken the windows. A broken window due to flying debris remains a possibility; there was a piece of debris imbedded in the frame

between two of the forward windows. We could not positively identify the origin of the debris or establish whether the event occurred in flight or at water impact. The same statement is true of the other crew compartment structure. Impact damage was so severe that no positive evidence for or against in-flight

pressure loss could be found.

Finally, the skilled and dedicated efforts of the team from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, and their expert consultants, could not determine whether in-flight lack of oxygen occurred, nor could they determine the cause of death. Joseph P. Kerwin

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard