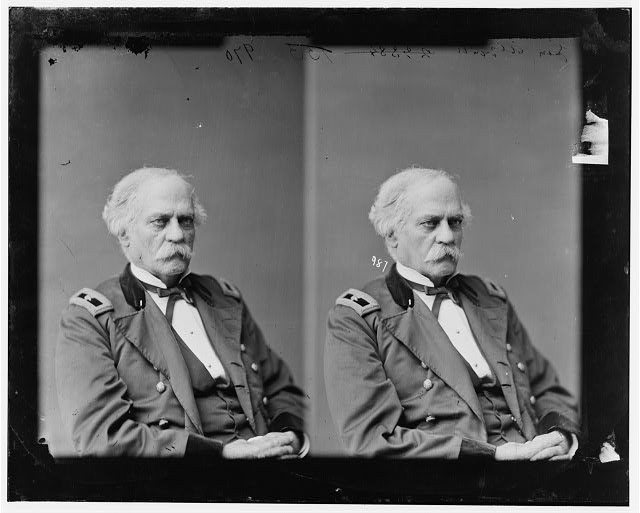

Benjamin Alvord, Brigadier General, United States Army, was born at Rutland, Vermont on 18 August 1813. He was a lineal descendant of Alexander Alvord who had settled in Connecticut about 1645.

Alvord entered the United States Military Aademy at the age of 16 and graduated in the class of 1833. For the next twenty-one years he was an officer of the 4th United States Infantry, serving with it continuously except for a two-year tour of duty as as instructor at West Point.

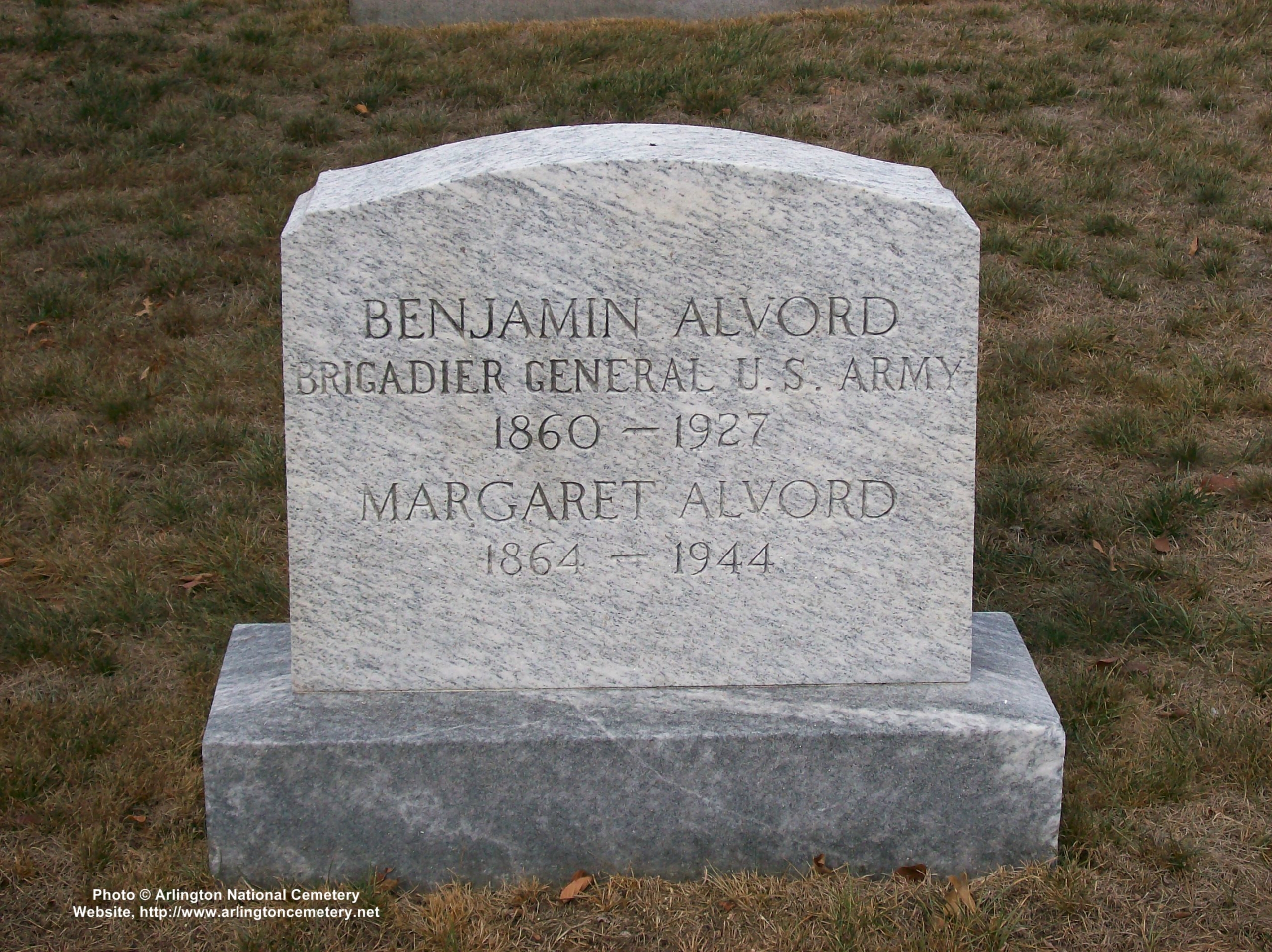

He served in the Florida Seminole War, the Mexican War and on the Western Frontier in the 1850s. He was appointed Brigadier General of Volunteers in April 1862 and placed in command of the Department of Oregon. He died in Washington, D.C. on 16 October 1884 and was buried in Section 4, Grave 2215-WS, of Arlington National Cemetery. His son, Benjamin Alvord, Jr. is buried nearby in Section 4.

A VETERAN OF THE SEMINOLE, MEXICAN AND CIVIL WARS

Death of Brigadier General Benjamin Alvord

His Long and Brilliant Military Career

WASHINGTON, October 18, 1884 – Brigadier General Benjamin Alvord of the United States Army, died yesterday at his home in this city. He was born in Vermont and was graduated from the Military Academy at West Point July 1, 1833. He was brevetted Second Lieutenant of the Fourth Infantry and began his duties by garrison services at Baton Rouge, where he remained until 1835. He was transferred to Key West and was promoted to the full rank of Second Lieutenant. From 1835 to 1837 he served in the Florida war against the Seminole Indians and took an active part in the skirmishes at Camp Izard in February and March 1836; in the action at Oloklikaha, March 31, 1836, and at Tholonotesessa Creek, April 27, 1836. On September 23 of the same year he was promoted to First Lieutenant. From 1837 to 1839 he was on duty at the Military Academy where on September 28, 1837 he was made Assistant Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy. In 1839 he once more went into active service on the frontier among the Cherokees, where he remained until 1841. He served at Fort Gibson, Indian Territory, in 1840, being Adjutant of the Fourth Infantry at the regimental headquarters from April 1 to July 29 and was subsequently engaged in frontier duty at Fort Smith in surveying military roads. In 1841 and 1842 he was again actively engaged in the wars in Florida against the Seminoles. He served in the noted expedition against “Billy Bowlegs” in the Big Cypress Swamp. From Florida he was transferred to frontier duty at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, where he was from 1842 to 1844. In 1844 and 1845 he was at Natchitoches, Louisiana, and was engaged subsequently in the military occupation of Texas. He served in the Mexican War and was on duty in the battles of Palo Alta and Resaca de la alma. On May 9, 1846, he was brevetted Captain for gallant and meritorious services in these battles. He was afterward Chief of Staff of Major Lally’s column on its march from Vera Cruz to the City of Mexico and was promoted to the full rank of Captain. He was afterward engaged in the defense of a convoy at Pasco Ovejas, August 10, 1847; at National Bridge, August 12; at Cerro Gordo, August 15 and Las Animas, August 19, and for gallant and meritorious services in these affairs was brevetted Major.

At the close of the war Major Alvord went into garrison duty at East Pascagoula, Mississippi. He served at various place on the Western Frontier until 1853, when he was placed in charge of the construction of a military road in Southern Oregon, and soon afterward was made paymaster of the Department of Oregon, which position he held until July 7, 1862. He served actively in the War of Rebellion from 1862 to 1865, and for his services therein was brevetted Lieutenant Colonel and Colonel, March 13, 1865, and Brigadier General August 8, 1865. He was in the Oregon District from 1862 to March 26, 1865; waiting ordered from that date until September 12, 1865 and paymaster in this city until March 15, 1867. He resigned as Brigadier General of Volunteers on August 8, 1865. In 1867 he was made Chief Paymaster of the District of Omaha, where he remained until April 15, 1869. He was then transferred to the District of the Platte, and in 1872 was made Paymaster General of the Army, with the rank of Colonel. He was made a Brigadier General on July 22, 1876. Since 1872 he has been on duty in Washington. He wrote a number of mathematical papers of great interest, including a memoir on “The Tangencies of Circles and of Spheres,” and “The Interpretation of Imaginary Roots in Questions of Maxima and Minima,” and a “Memoir on the Intersection of Circles and the Intersection of Spheres.” The University of Vermont conferred upon him the degree the M.M. in 1854.

Brigadier General Benjamin Alvord was born, August 18, 1813, at Rutland, Vermont. Here he grew up to manhood an earnest youth, studious in habit, and imbibing an ardent love of nature from every fountain of the beauty and grandeur of his native State, diversified by hills and valleys, elevated plateaus and soaring mountains, and fringed on one side with historic lakes, and on the other with the most picturesque of rivers. Here he learned the lessons of patriotism which have characterized the Green Mountain boys since the days of Ticonderoga and Bennington. And here, by the example of Allen, Stark, Warner, and other Revolutionary heroes, was implanted that love of military fame which made the enthusiastic lad a soldier of his country.

At the age of sixteen, Alvord entered the Military Academy, where he developed decided mathematical talents, being always among the first to work out difficult extra problems, and was noted for his ingenious application of geometrical methods in their solution.

Upon his graduation, July 1, 1833, he was promoted to the Fourth Infantry, in which distinguished regiment he served over twenty years, himself adding not a little to its merited reputation. After two years of garrison duty at Baton Rouge and Key West, he went to Florida, the Seminole War having opened with Dade’s Massacre and the threatened destruction of the population of the State, for none could tell at what moment, or in what manner, they would be assailed and subjected to the most cruel and brutal death. Though the troops did their best and fought bravely at Camp Izard, Oloklikaha, and Thlonotosassa Creek, in all of which actions Alvord took an active part, the campaign of 1836 was a failure, and, without any knowledge of the county, it could scarcely be otherwise. The theatre of operations was in a dense wilderness, where every hommock and swamp was a natural citadel garrisoned by unseen savages, who could sortie from their places of safety to the attack of exposed parties, and, if pressed, return to their hiding places with the the fleetness of deer.

Alvord was soon relieved from the constant watching, daily disappointments, and weary marches against this Parthian foe, for a more congenial employment at the Military Academy as an Assistant Professor of Mathematics, from which department he was soon transferred to become the Principal Assistant Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy, holding that position, to the great advantage of the Academy, till Aug. 28, 1839, when he was ordered to frontier duty in the Indian Territory, where at various posts he remained two years.

The Florida War had continued with varying success, when, in 1841, Alvord was again ordered to that pestilential region. While the northern settlements of the State were as well protected as human skill and military means could devise, the available force of the Army, aided by the Navy, was directed against the Southern Indians, who counted upon all immunity from danger, environed as they were by swamps, deep mud, mangrove bushes, and a large expanse of everglades. Here were to be seen dragoons wading in water waist-deep, the artillery and infantry picking their way along oozy paths amid cypress stamps and shining alligators, and sailors and marines alternately serving in boats and on dry land. With fortitude, for months, all bore the toils and privations of this amphibious life in the Big Cypress Swamp till the Indians were dispersed, and taught that white men could penetrate to their securest strongholds.

From Florida, Alvord again went to the Western frontier, and in July 1845, joined the “Army of Occupation,” under General Taylor, to take possession of Texas, which “had become an integral part of our Union.” This involved the United States in the War with Mexico, hostilities beginning upon the Rio Grande, where were fought the Battles of Palo Alto and Resaca-de-la-Palma, in both of which Alvord participated and won his brevet of Captain for his “gallant and meritorious conduct” in these engagements.

For a year Alvord was detached on recruiting service, after which he gain took the field as Chief of Staff of Major Lally’s column, “a little more than a thousand strong,” convoying sixty-four wagons from Vera Cruz to the City of Mexico. The Mexican guerillas (1,200 to 2,000) believing that a large quantity of specie was being transported in the train, attacked it, August 10, 1847, at Paso de Ovejas, – a strong position behind the ruins of a stone house upon a hill. In this spirited engagement, “Alvord,” says major Lally, “distinguished himself by his example of coolness and courage in rallying the men, and leading them up to charge the height and stone house in front and on the right, from which the enemy delivered a very heavy fire.” On the twelfth, Lally’s column was again met in force by the enemy at the National Bridge, but, though our loss was severe, the guerrillas were beaten and forced to retreat. The struggle was renewed with vigor on the fifteenth, from the various strongholds of Cerro Gordo, where, four months before, General Scott had gained a great victory over Santa Anna. Though the enemy had been severely punished in these engagements, a fourth attack was made on the nineteenth, at Las Animas. In this last, Major Lally being wounded, the command of the column devolved upon Captain Alvord, who continued its march to the city of Jalapa, which he occupied the next day. In this series of actions great gallantry, fortitude, and perseverance had been shown by these raw troops, whose total casualties amounted to one hundred and five, while those of the enemy were much greater. Alvord’s dauntless pluck, skillful leadership, and good judgment did much for our success, and his merits were recognized by the bestowal upon him of the brevet of Major “for gallant and meritorious conduct” in these engagements.

Lally’s command, after resting at Jalapa to refit the train, recruit the animals, and provide for the sick and wounded, resumed its march, and under General Lane, whom Lally had joined, encountered Santa Anna, with four thousand Mexicans, on October 9th, at Huamantla, in which combat Alvord did good service.

After the Mexican War had terminated, Alvord was in garrison at various posts. While in Southern Oregon, constructing a military road, he was appointed, June 22, 1854, a Paymaster with the rank of Major, and for six years continued in Oregon as the Chief Paymaster of that department.

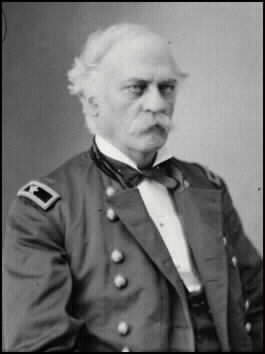

Upon the breaking out of the War of the Rebellion, Alvord hastened to offer his services for active duty in the field. President Lincoln, so soon as apprised of Alvord’s military qualifications and high character, appointed him, Apr. 15, 1862, a Brigadier-General, U. S. Volunteers, and assigned him to the command of the Direst of Oregon, embracing nearly the same territory as the present Department of Columbia. Although far from the scene of actual hostilities, his command was by no means an unimportant one. Fidelity, prudence, decision, and vigilance were absolutely needed, and these he possessed in an eminent degree. His administration of military affairs in this district, remote from Washington, from July 7, 1862, to March 26, 1865, required great discretion, and it is needless to say that he acquitted himself of his trust to the entire satisfaction of the Government, which bestowed upon him three brevets for his “faithful and meritorious services.”

Alvord resigned his Brigadier-Generalship of Volunteers, Aug. 8, 1865, and resumed his duties of Paymaster at New York city, from whence he was transferred as Chief Paymaster of the District of Omaha till Apr. 15, 1869, and then of the Platte till Dec. 28, 1871. His long and valuable services now reaped their reward, he being appointed Chief of the Pay Department with the rank of Colonel, Jan. 1, 1872, and of Brigadier-General, July 22, 1876. This elevated position he held till retired from active service, June 8, 1880, with great credit to himself, reflecting honor upon the Army, and with manifest advantage to the Government.

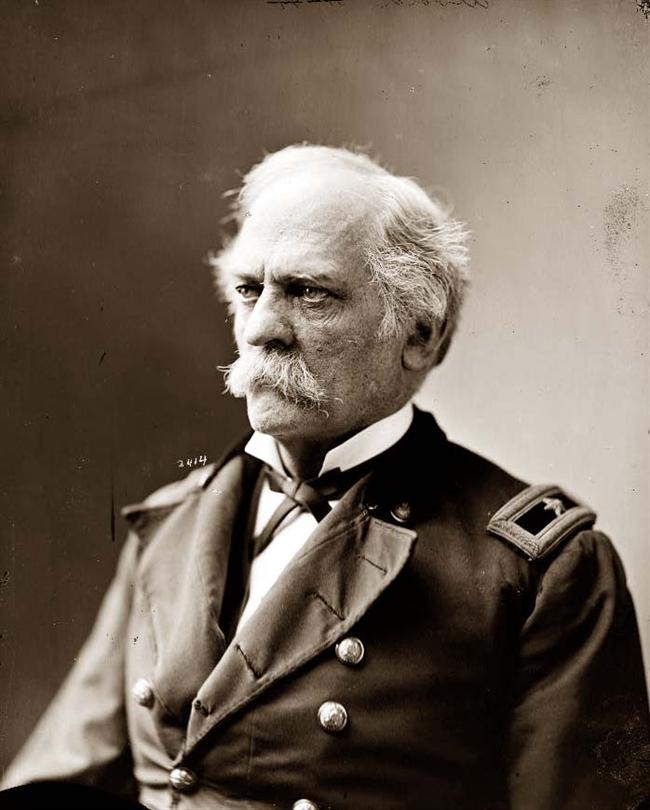

From the foregoing narrative it will be seen that General Alvord lived most of his life in the field, where he was separated from society and books, yet he became a learned scholar; skilled in dialectics, ready in conversation, and polished in his writing. He had a special fondness for mathematics, botany, history, and biography, upon all of which subjects he prepared instructive and sometimes quite original papers. A singular fatality attended his higher labors. The manuscript of a History of the Mexican War was lost in the wreck of the Southerner on Cape Flattery, December, 1854, and a mathematical treatise, accepted for publication by the Smithsonian Institution, was lost in the fire in their building, January, 2865. The latter was re-written with additions, and published in the “American Journal of Mathematics,” 1882.

The most notable of Alvord’s mathematical memoirs were those on “The Tangencies of Circles and Spheres” and the “Intersections of Circles and Spheres.” The first of these memoirs, now well known, created much interest when it appeared. The latter memoir is a generalization of the former, the problems involved being: First, to draw a circle which shall make a certain given angle with three given circles. Second, to draw a sphere which shall cut each of four given spheres at the same angle. The problems are solved by purely geometrical processes. As the solution of the question of Tangencies of Circles in the Spheres, in like manner the question of the Intersection of Circles is extended to the Intersection of Spheres. The whole solution is based on the principle of converging chords, giving a unity to both memoirs as accomplishing a generalization of the entire problem.

Alvord’s paper on “Winter Gazing in the Rocky Mountains” is a startling revelation, in published form, of an established fact unknown till 1869, that, in the coldest weather and without shelter, all the domestic animals can find ample food on the nutritious summer-cured grasses, and that myriads of these animals are yearly raised on the elevated, arid, yet mild plateaus of the West, embracing an area of a million square miles, or about one fourth of our whole territory. The article fully explains how the grasses in the Rocky Mountains, as they stand on the soil, are cured by the summer’s sun, the heat drying them, and thus retaining and concentrating in the stalk the sugar, gluten, and the other constituents of which they are composed. He also shows how the fine dry snows of these regions are drifted into the valley, leaving the uplands uncovered for grazing.

Alvord, as a soldier, was zealous and efficient in the performance, for half a century, of every duty devolving upon him; as a mathematician, he had a high capacity, particularly for geometrical investigations, in which he had few superiors; as a botanist, he was a close observer of nature, many of whose curious secrets he discovered; in historical and literary lore he was one of the best informed officers in the army; and as a writer, he wielded a fluent, forcible, and perspicuous pen. But it was in his personal relations that Alvord was most attractive. Though ordinarily grave, he was never austere and gloomy; studious and contemplative, he had no arrogance of intellect; ;his matured wisdom continually welled out into new fountains of thought; his conversation, earnest, refined, and often playful, was always instructive; and whatever he wrote was trustworthy and sparkled with strong brain-force. His moral beauty of character surpassed his intellectual. Every one who knew him in social life respected and loved him, so genial was his humanity and so broad his charity. Abounding in sympathy, benevolence, and kindness to his fellows, he was necessarily tolerant of their infirmities. Though he was in temper as gentle as a child and in manner as modest as a maiden, it was not from weakness, as those best knew who met him in debate or upon the battlefield. Always considerate of others, he was most exacting to himself, manfully bearing his own burdens, which he never sought to cast upon other shoulders. In fine, Alvord was a most useful officer, a sterling patriot, a devoted husband and father, a generous and tender-hearted friend, and a thorough Christian gentleman.

Died, October 16, 1884, at Washington, D. C.: Aged 71.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard