Improving access to behavioral health care for migrants and their families

Perhaps more than ever, military personnel and their families need access to mental health services. But research shows that the longer people have to travel for care, the less likely they are to seek it.

How many service members and their families are denied behavioral health care? Can access to care be improved?

The conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan have had a significant impact on the emotional and mental well-being of many service members and their families. The “invisible wounds” of war-depression, anxiety, traumatic brain injury, and substance abuse problems-are common among returning soldiers. Many spouses and children of deployed soldiers also suffer from high levels of anxiety and depression, which can ultimately affect their job and school performance.

There are a number of ways in which military members and their families can get help. Specialists, including counselors, psychiatrists, and psychologists, offer their services to military members in treatment centers, community social service agencies, and private practices.

But while many service members and their families receive mental health support, the Department of Defense is concerned that many live too far from the support they need to help them cope and reintegrate into civilian life.

RAND researchers conducted the first comprehensive study of behavioral health care access for military personnel and their families in remote geographic areas and made a series of recommendations based on quantitative and qualitative analysis.

Living more than 30 minutes from care makes access difficult

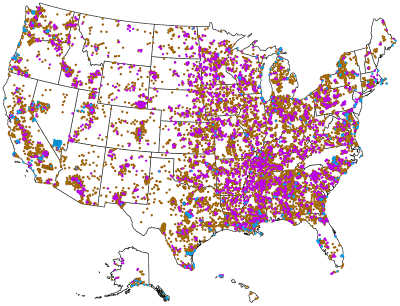

Among civilians, geographic remoteness is often associated with rural areas of the United States, i.e., sparsely populated regions such as Appalachia, the Ozarks, and the Intermountain West.

Among military personnel, we also find that many people who are not located in rural areas are distant from mental health care. People who live in remote areas, including military personnel and their families, face a number of distance-related challenges in seeking and receiving mental health care.

Care providers are scarce

Approximately 80% of rural areas in the United States are classified as medically underserved, meaning areas lacking doctors, dentists, nurses, and other health care professionals. Medically underserved areas also tend to lack psychiatrists, psychologists and therapists. Although military treatment centers are sometimes located in remote areas, they do not reach all isolated soldiers and their families.

Increased travel time reduces the need for treatment

Studies of civilian and veteran mental health have shown that time is a critical factor in seeking care. For some mental health issues, even a mile away can mean the difference between getting treatment and not getting treatment.

Transportation alternatives and ways are limited

In rural areas of the United States, public transportation alternatives are notoriously scarce. And some returning service members may need these options because of a physical disability.

Who are the people with distance problems?

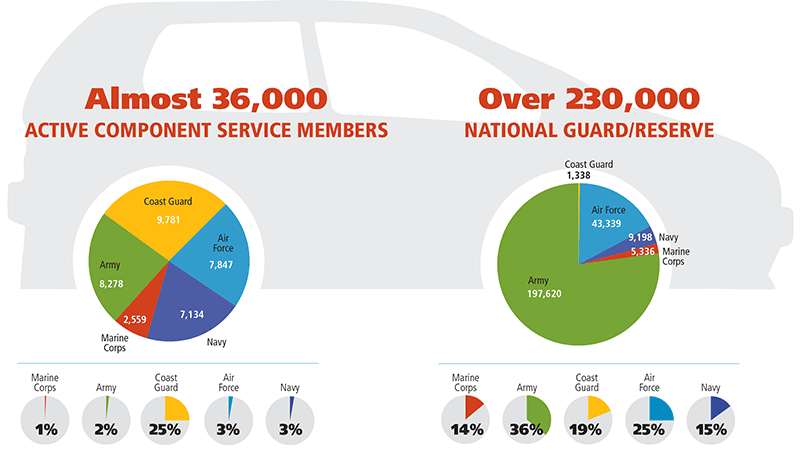

The pie charts above show the percentage of full-time active duty service members by duty station who are behavioral health remote. It is worth noting that the Coast Guard has the highest percentage of active duty service members living at least 30 minutes away from mental health professionals (9,781), a significantly higher percentage (25%) of all service members than the other services, where the percentage ranges from 1% to 3%. This is due to the fact that the Coast Guard locates many of its duty stations away from military medical facilities and in areas designated as health professional shortage areas.

The pie charts above show the percentage of National Guard/Reserve soldiers who are far from behavioral health care. All armed forces have a part-time reserve component. Notably, in the Army Reserve, the vast majority of component employees (197,620) live 30 minutes or more from behavioral health specialists, which is a larger percentage (36%) of the total number of components than in the other services.

RAND researchers conducted a geospatial analysis using data on the residences of military personnel and their dependents and applied the 30-minute commute rule to estimate the distance military personnel must travel.

While more part-time military personnel live 30 minutes or more from care, they are less affected by distance, meaning they are more likely (after diagnosis) to receive behavioral health care than their full-time active component counterparts who live farther away. This may be due to the fact that reservists have more insurance options because they often work full-time outside the military.

1.3 million people live at least 30 minutes from a mental health facility or in a low provider density area.

- 35,599 Active component

- 256,831 National Guard and Reserve

- 1,098,839 dependents

RAND identified that approximately 1.3 million military personnel and their dependents are geographically distant from mental health care. Specifically, approximately 1 million dependents (children and spouses) and 300,000 service members live far from needed care.

3 steps to improve access

1. Set targets for improvement

- Set an official maximum time to access care of 30 minutes

- Set a goal of nearly 100% access to behavioral health care for full-time active component members in the United States.

- Set goals to increase access for National Guard and Reserve members and all military dependents.

2. Monitor the effectiveness of implementation

- Design and implement an interactive data portal to track access to health care for service members and their dependents.

- Develop, test, and evaluate alternative methods of remote health service management, using it as a measure of the effectiveness of the monitoring system.

- Support improved monitoring by having regional health care providers share their provider database with DOD.

3. Explore program alternatives

- Continue to integrate behavioral health care into primary care and explore new options.

- Increase the use of telemental health (TMH), a program that uses telecommunications and video technology to overcome the challenges of distance by enabling synchronous communication between clinicians and their patients in real time. To be successful, it is critical that the military health care system continue to measure the effectiveness of telehealth and collaborative care and remove outdated technical and regulatory barriers.

Read our general and most popular articles

- Diaetoxil

- Nuubu

- Regener 8

- CBD Vital

- Nordic Oil

- Potencialex

- Diaetostat

- Figur Kapseln

- Viscerex

- Prostaphytol

- Nutra Prosta

- Nutra Flex

- Diaetolin

- Matcha Slim

- Hepafar Forte

- Derila Kissen

- Exodermin

- HHC

- HHC Vape

- KU2 Cosmetics Hyaluronsäure Serum

- Liba Capsules

- KetoXplode

- Green Gummies

- Liver Ignite

- Ketoxboom Fruchtgummis

- Viagra Alternative

- Gundry MD Energy Renew

- ProDentim

- Phentermine Over The Counter

David W. Newton is a board certified pharmacist and also has been a board member for boards of examiners for the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy since 1983. His areas of expertise are primarily pharmaceuticals as well as cannabinoids. You can read an article about his expertise in CBD on the National Library of Medicine.

Reviewed by: Kim Chin and Marian Newton