Brain injury has been described as a typical injury of modern warfare. Between 30% and 50% of injuries sustained in the recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan were caused by improvised explosive devices, and TBIs are often the result of these events. However, the majority of concussions occur when service members are off duty and are the result of training accidents, falls, sports, motor vehicle accidents, and other serious trauma.

Eighty-four percent of these injuries are considered mild traumatic brain injuries (MTBI) or concussions. To date, there have been no population-based studies of service members diagnosed with mTBI, their post-diagnosis care, and their health care needs.

Mild cases of mTBI can be difficult to identify and treat because symptoms, comorbidities, and other factors may vary. In order to provide the most effective and efficient care for service members with mTBI, it is important to first understand how many and which service members are diagnosed, where they receive care, what care is provided, and how long that care lasts.

The ultimate goal of improving care – and outcomes – for these service users depends on a solid data base. The RAND study took a first step toward filling this gap by examining the population of service users diagnosed with mTBI and the characteristics of the care they receive outside of services.

As the number of brain injuries among active duty military personnel has increased, so has the number of brain injuries diagnosed by the military health system (MHS) – from 12,470 in 2002 to a peak of 32,668 in 2011, according to data from the Center for Brain Injury in Defense and Veterans Affairs.

The most common symptoms of mTBI are headaches, sleep disturbances, dizziness and balance problems. In addition, mTBI is often associated with mental health problems such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

The RAND study focused specifically on the population of non-active service users with a new diagnosis of mTBI in calendar year 2012, the last full year for which data were available at the time of the study. The study used patient health data from the MHS database, which contains information on all MHS fee-for-service health services (these data did not include information on the care provided to service members during deployments).

Which staff members were diagnosed with mTBI?

The study revealed several trends in the demographic and service-related characteristics of non-active service members newly diagnosed with mTBI in 2012:

- They were generally between the ages of 18 and 34 and were on active duty with an average of six years of military service. Two-thirds of them had a history of deployment.

- About 10% had received prior treatment for TBI between 2008 and 2011.

Service members were diagnosed with MBCT at multiple sites, with about 58% diagnosed at a military treatment center. Of those who were not diagnosed, 80% were diagnosed at a civilian outpatient clinic. The vast majority of service members visited a military medical center during their next medical visit. However, these visits took place in different settings, such as primary care clinics and behavioral health or neurology clinics. Because these soldiers receive diagnosis and treatment from many different providers, coordination and follow-up can be difficult. In fact, MHS data revealed many inconsistencies in how diagnoses and follow-up visits were coded, suggesting the need for coordination of care across providers.

What are the most common health problems among service users with spinal cord injury?

Diagnostic coding guidelines recommend that providers record the diagnosis of mTBI at the patient’s first post-injury visit, but subsequent visits are coded according to the patient’s symptoms. To obtain a complete picture of the care service users received following an mTBI, it was necessary to identify conditions that may be associated with the mTBI.

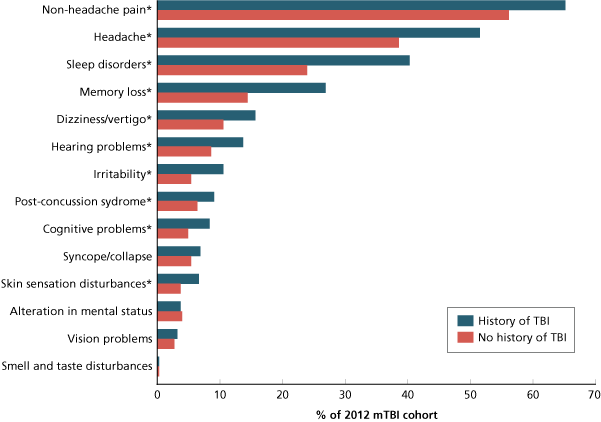

Among service members diagnosed with mTBI in 2012, the most common conditions treated within 6 months of the mTBI diagnosis were headaches (57%) and headaches (40%). 26% received treatment for sleep disorders. Health problems often associated with mTBIs (e.g., headaches) were treated more often in the six months following mTBI diagnosis than in the previous six months.

As shown in Figure 1, service members in the mTBI cohort with a prior diagnosis of CBT were significantly more likely to receive treatment for these conditions than those without CBT. It should be noted that individuals with mTBI may receive treatment for more than one symptom or co-occurring condition.

Service members with a history of MBCT were more likely to receive treatment for several of the health problems commonly associated with MBCT within 6 months of MBCT diagnosis.

* Statistically significant difference p < 0.0001.

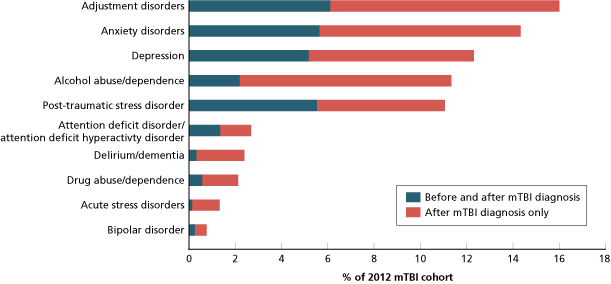

Co-diagnosed mental health problems were also included in the analysis. The study examined the proportion of soldiers who received treatment for these conditions in the 6 months prior to the 2012 mTBI diagnosis and in the 6 months after diagnosis, as shown in Figure 2.

Soldiers were most likely to receive treatment for a behavioral health condition within 6 months of mTBI diagnosis.

NOTES: Anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety disorder not otherwise specified, and panic disorder. Depression includes major depression and dysthymia.

Of those who received treatment for a behavioral disorder within six months of diagnosis of MST, 50-70% had not received such treatment in the six months prior to diagnosis.

There are several possible explanations for this pattern of treatment before and after mTBI. For example, behavioral problems may have developed as a result of a moderate traumatic injury or as a psychiatric reaction to the incident in which the service member was injured. Alternatively, pre-existing behavioral disorders may have been identified as a result of the patient’s use of the health care system.

Individuals with a history of post-traumatic stress disorder were significantly more likely to receive treatment for specific behavioral disorders in 2012 after a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder.

One-third of those in service had a CT scan within six months of a TBI diagnosis. Other common assessments were psychiatric diagnostic evaluations (28%) and physical therapy evaluations (25%).

What type of care do service members with TBI receive within six months of TBI diagnosis?

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (DoD) clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of mTBI recommend limiting physical and mental activity and remaining in a low-stimulus environment immediately after a stroke. If symptoms persist, the guidelines recommend further evaluation and treatment based on symptoms.

The majority of the 2012 mTBI cohort did not receive treatment for symptoms and comorbidities after diagnosis of mTBI or received treatment for only a short time, indicating that these patients generally recovered quickly.

One-third of those in service received a CT scan within 6 months of mTBI diagnosis. Other common assessments were psychiatric diagnostic evaluations (28%) and physical therapy evaluations (25%).

Thirty percent received psychotherapy within six months of TBI diagnosis. Physical therapy (24%) or complementary/alternative medicine (10%) were less common. Medication use was common; 60 percent filled a prescription for analgesics, 45 percent filled a prescription for opioids, and 24 percent filled a prescription for antidepressants within six months of TBI diagnosis.

Those with a history of TBI were more likely to receive diagnostic evaluations, psychotherapy, physical therapy, and other treatments, as well as commonly prescribed medications for TBI-related symptoms.

The majority of the 2012 mTBI cohort did not receive treatment for symptoms and comorbidities after a diagnosis of mTBI or received treatment for only a short time, suggesting that these patients generally recovered quickly.

Which service members have ongoing treatment needs?

Although the majority of service users with mTBI received treatment for only a short period of time after diagnosis, a significant minority (10-20%) continued treatment for three months or more after diagnosis. This period of treatment is considered permanent. Those who received ongoing treatment received significantly more diagnostic assessments and therapies than their counterparts who did not have long-term problems. T

hey were also much more likely to be diagnosed with conditions commonly associated with mTBI. For example, about 70% were diagnosed with a memory or sleep disorder within six months of being diagnosed with mTBI in 2012, compared with 10% of those who did not receive long-term treatment.

Recommendations

The clinical and administrative data available for service members diagnosed with mTBI posed several challenges in describing this population and their care, and in determining their ongoing care needs. The following recommendations identify areas where the MHS could improve data collection and care coordination practices to provide more information to improve care and outcomes for service members with mTBI.

Identify opportunities for care coordination

Service members diagnosed with mTBI receive care in many different clinical settings, not just military installations. It is important for the MHS to understand the challenges and strategies of care coordination and identify best practices.

Assessing the quality of care provided to service personnel with mTBI

In the future, these analyses should be expanded to consider not only the type of care provided, but also the quality of care provided. These studies should include additional data sources, as current administrative data are insufficient to assess provider compliance with clinical care recommendations. Given the variability in symptom presentation and recovery, health care providers should develop clearer standards of care for mTBI.

Improve coding practices and review existing TBI coding guidelines

Good management information should be considered an essential component of quality care, as it tracks patient status as well as treatments and procedures. DoD TBI coding guidelines require providers to record a TBI diagnosis only on the first visit, with subsequent visits to be coded with the appropriate OED diagnosis codes.

Therefore, it is not possible to use administrative data to track changes in mTBI management over time. The Army should consider whether the benefits of current TBI coding guidelines outweigh the drawbacks of understanding the nature of care for service members with TBI.

Improve data quality to increase research capacity

Administrative data are collected for a variety of purposes, including legal and financial oversight, but are largely unrelated to monitoring and research. This limits the usefulness of the data for analysis. Improving the linkage between administrative requirements and other clinical data (e.g., pharmaceutical systems and data) would facilitate a wide range of research activities.

Conduct additional research on the conditions and treatment of service users with mTBI. The purpose of this study was to provide a foundation for hypothesis-driven clinical trials. To this end, several areas should be explored through multivariate analyses to allow the MHS to confirm and interpret associations between patient, clinician, and environmental factors in the treatment and outcomes of service members with mTBI.

Multivariate regression allows for multiple variables to be considered and to determine whether observed differences may be due to other factors. Future analyses should focus particularly on treatment patterns and their predictors, differences in diagnosis and treatment, and the cohort with persistent mTBI-related problems.

Even mild TBI-the most common type of TBI-can cause persistent problems in military personnel, and those who have experienced multiple TBIs are much more likely to be diagnosed with comorbidities. Given the prevalence of injuries, both on and off the battlefield, it is critical to understand which service members are experiencing these injuries. A better understanding of their symptoms and treatment can help us understand the needs of these soldiers, which will help ensure they receive quality care and achieve the best possible outcomes.

Read our general and most popular articles

- Diaetoxil

- Nuubu

- Regener 8

- CBD Vital

- Nordic Oil

- Potencialex

- Diaetostat

- Figur Kapseln

- Viscerex

- Prostaphytol

- Nutra Prosta

- Nutra Flex

- Diaetolin

- Matcha Slim

- Hepafar Forte

- Derila Kissen

- Exodermin

- HHC

- HHC Vape

- KU2 Cosmetics Hyaluronsäure Serum

- Liba Capsules

- KetoXplode

- Green Gummies

- Liver Ignite

- Ketoxboom Fruchtgummis

- Viagra Alternative

- Gundry MD Energy Renew

- ProDentim

- Phentermine Over The Counter

David W. Newton is a board certified pharmacist and also has been a board member for boards of examiners for the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy since 1983. His areas of expertise are primarily pharmaceuticals as well as cannabinoids. You can read an article about his expertise in CBD on the National Library of Medicine.

Reviewed by: Kim Chin and Marian Newton