Combat Infantryman’s Badge

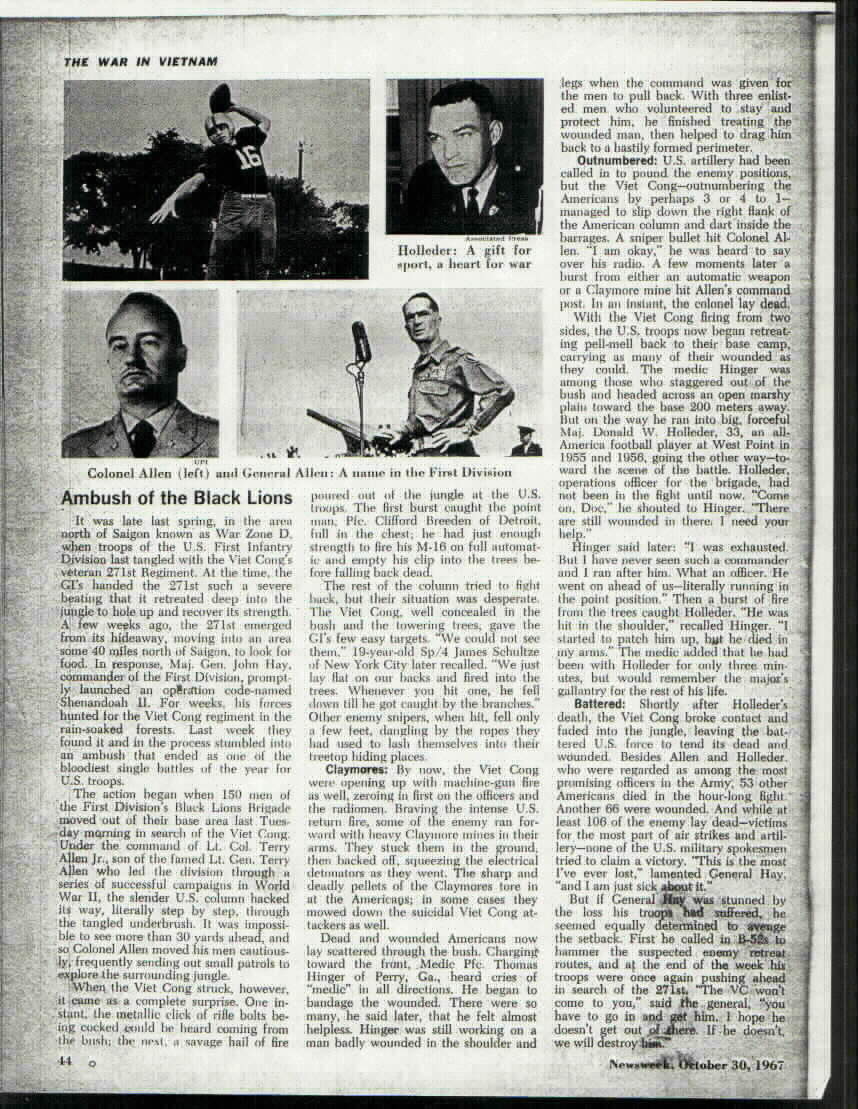

Born in 1934, Donald W. Holleder graduated from West Point and was a football All-American while attending the academy.

He was Operations Officer under Lieutenant Colonel Terry de la Mesa Allen, Jr., in the 1st Infantry Division in Vietnam. When Allen was killed-in-action in a battle which took place 40 miles from Saigon on October 17, 1967, Holleder made his way to the front to take command of the Brigade and was also killed.

The father of four children, he was the principal in a surprise switch by Colonel Red Blaik, Army’s football coach at West Point, that was considered the main reason for Army’s upset 14 to 6 win over Navy in 1955. He was regarded as one of the finest ends in collegiate football in 1954, but midway through the 1955 season he was shifted to quarterback.

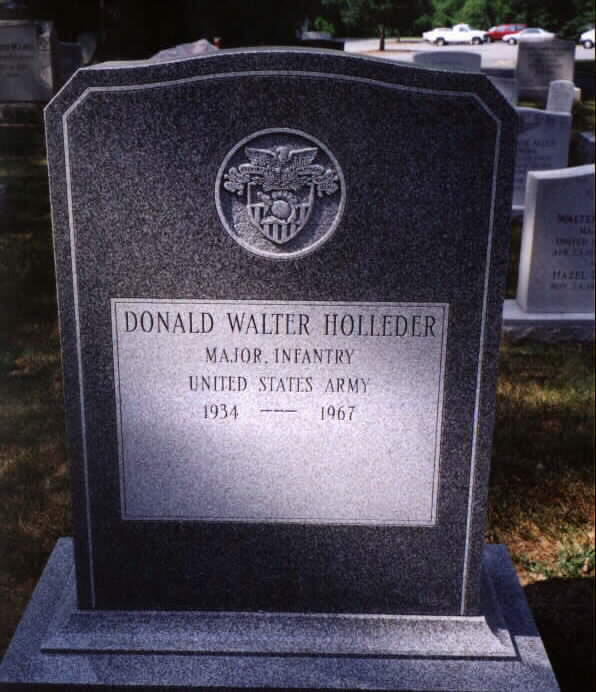

HOLLEDER, DONALD WALTER

MAJ USA

DATE OF BIRTH: 08/03/1934

DATE OF DEATH: 10/17/1967

BURIED AT: SECTION 1 SITE 168-A

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

“I was a combat medic with the 2/28th Inf. Black Lions when Major Holleder was killed. In fact, a good friend of mine, Tom Hinger was with him when he was killed by the sniper.

“Attached, you will find a scan of a photo which was taken the morning of 17 October 1967. Included in the picture are, starting from the left: Colonel George Newman, 1st Bde. Commander; Lieutenant Colonel Terry Allen Jr., 2/28th Infantry Commander; Major Donald Holleder, brigade S-3; Brigadier General William Coleman, Assistant Division Commander; and First Lieutenant Albert Welch, Delta Company Commander.

“The photo was taken by SP5 Verland Gilbertson, who was a combat photographer, attached to the unit for Operation Shenandoah II. He was killed during the ambush and the film was recovered. The photo was included in an article about the operation in the 1st Infantry Division magazine “Danger Forward”, published in June 1968.

“Major Holleder had just gone from 2/28th to Brigade a short time before this operation. During the battle the command element had been overrun and there was chaos in the field. Two rifle companies had been caught in patrol formation and were unable to set up a defensive perimeter to defend themselves. Consequently, individual soldiers and small groups had to defend themselves against a much larger enemy force which included hard-core Viet Cong from the 271st VC Regiment, NVA Regulars, and at least one Chinese advisor (found dead after the battle). A

perimeter was set up in a draw a few hundred meters from the ambush site and wounded were being brought there.

“Major Holleder overflew the area and saw a whole lot of Viet Cong and many American soldiers, most wounded, trying to make their way out of the ambush area. He landed and headed straight into the jungle, gathering a few soldiers to help him go get the wounded. A sniper’s shot killed him before he could get very far. He was a risk-taker who put the common good ahead of himself, whether it was in giving up a position in which he had excelled or putting himself in harm’s way in an attempt to save the lives of his men. My contact with Major Holleder was very brief and occurred just before he was killed, but I have never forgotten him and the sacrifice he made. On a day when acts of heroism were the rule, rather than the exception, his stood out.

“After getting out of the Army in ’68, I worked for a few years and then got married and went back to college with a major in Nursing. I went back on Active Duty in 1976 as an Army Nurse Corps officer. I retired in 1995 as a Lieutenant Colonel and am currently the Director of Surgical Services in a Medical Center in California. Most of what I

learned about leadership was learned by example (good and bad) when I was a 20 year old draftee medic in Vietnam. Major Holleder was definitely one of the good examples.

“Last year a number of us got together at a 1st Infantry Division reunion in Alexandria. It was the first time I had seen anyone from my unit in almost 30 years. Three of us: Tom Hinger, Steve Goodman (Goody), and I went to Alexandria and visited the gravesites of Lieutenant Colonel Allen and Major Holleder. It was especially meaningful for them, because they were both with him when he was killed. In fact, Goody killed the sniper who shot Major Holleder. They are both great guys, brave soldiers, and true friends.”

Don Holleder was an All American end on the Red Blaik coached Army football team which was a perennial eastern gridiron power in 40s and 50s. On Fall days I would run home from the post school, drop off my books, and head directly to the Army varsity practice field which overlooked the Hudson River and was only a short sprint from my house.

Army had a number of outstanding players on the roster back then, but my focus was on Don Holleder, our All-America end turned quarterback in a controversial position change that had sportswriters and Army fans buzzing throughout the college football community that year.

Don looked like a hero, tall, square jawed, almost stately in his appearance. He practiced like he played, full out all the time. He was the obvious leader of the team in addition to being its best athlete and player.

In 1955 it was common for star players to play both sides of the ball and Don was no exception delivering the most punishing tackles in practice as well as game situations. At the end of practice the Army players would walk past the parade ground (The Plain), then past my house and into the Arvin Gymnasium where the team’s locker room was located.

Very often I would take that walk stride for stride with Don and the team and best of all, Don would sometimes let me carry his helmet. It was gold with a black stripe down the middle and had the most wonderfull smell of sweat and leather. Inside the helmet suspension was taped a sweaty number 16, Don’s jersey number.

While Don’s teammates would talk and laugh among themselves in typical locker room banter, Don would ask me about school, show me how to grip the ball and occasionally chide his buddies if the joking ever got bawdy in front of “the little guy”. On Saturdays I lived and died with Don’s exploits on the field in Michie Stadium.

In his senior year Don’s picture graced the cover of Sports Illustrated magazine and he led Army to a winning season culminating in a stirring victory over Navy in front of 100,000 fans in Philadelphia. During that incredible year I don’t ever remember Don not taking time to talk to me and patiently answer my boyish questions about the South Carolina or Michigan defense (“I’ll bet they don’t have anybody as fast as you, huh, Don?”).

Don graduated with his class in June 1956 and was assigned to the 25th Infantry Division in Schofield Barracks, Hawaii. Coincidently, my Dad was also assigned to the 25th at the same time so I got to watch Don quarterback the 14th Infantry Regiment football team to the Division championship in 1957.

There was one major drawback to all of Don’s football-gained noteriety – he wanted no part of it. He wanted to be a soldier and an infantry leader. But division recreational football was a big deal in the Army back then and for someone with Don’s college credentials not to play was unheard of.

In the first place players got a lot of perks for representing their Regiment, not to mention hero status with the chain of command. Nevertheless, Don wanted to trade his football helmet for a steel pot and finally, with the help of my Dad, he succeeded in retiring from competitive football and getting on with his military profession.

It came as no surprise to anyone who knew Don that he was a natural leader of men in arms, demanding yet compassionate, dedicated to his men and above all fearless. Sure enough after a couple of TO&E infantry tours his reputation as a soldier matched his former prowess as an athlete.

It was this reputation that won him the favor of the Army brass and he soon found himself as an Aide-de-camp to the four star commander of the Continental Army Command in beautiful Ft Monroe,Virginia.

With the Viet Nam War escalating and American combat casualties increasing every day, Ft Monroe would be a great place to wait out the action and still promote one’s Army career – a high-profile job with a four star senior rater, safely distanced from the conflict in southeast Asia.

Once again, Don wanted no part of this safe harbor and respectfully lobbied his boss, General Hugh P. Harris to get him to Troops in Viet Nam. Don got his wish but not very long after arriving at the First Division he was killed attempting to lead a relief column to wounded comrades caught in a Viet Cong ambush.

I remember the day I found out about Don’s death. I was in the barber’s chair at The Citadel my sophomore year when General Harris (Don’s old boss at Ft Monroe, now President of The Citadel) walked over to me and motioned me outside.

He knew Don was a friend of mine and sought me out to tell me that he was KIA. It was one of the most defining moments of my life. As I stood there in front of the General the tears welled up in my eyes and I said “No, please, sir. Don’t say that.” General Harris showed no emotion and I realized that he had experienced this kind of hurt too many times to let it show. “Biff”, he said, “Don died doing his duty and serving his country. He had alternatives but wouldn’t have it any other way. We will always be proud of him, Biff.”

With that, he turned and walked away. As I watched him go I didn’t know the truth of his parting words. I shed tears of both pride and sorrow that day in 1967, just as I am doing now, 34 years later, as I write this remembrance. In my mind’s eye I see Don walking with his teammates after practice back at West Point, their football cleats making that signature metallic clicking on concrete as they pass my house at the edge of the parade ground; he was a leader among leaders.

As I have been writing this, I periodically looked up at the November 28, 1955 Sports Illustrated cover which hangs on my office wall, to make sure I’m not saying anything Don wouldn’t approve of, but he’s smiling out from under that beautiful gold helmet and thinking about the Navy game. General Harris was right. We will always be proud of Don Holleder, my boyhood hero.

Biff Messinger, Mountainville, New York

Army’s Holleder delivered where he was needed

He led on the ball field and the battlefield.

In 1955, he had been the improbable quarterback in Army’s improbable upset of Navy. Twelve years later, heading into a Vietnamese jungle, into the smoky heart of a battle he did not have to join, Major Donald W. Holleder was running again.

“I couldn’t keep up with him,” recalled Tom “Doc” Hinger, an Army medic during that bloody October 1967 clash with North Vietnamese regulars in Ong Thanh. “His legs were churning. He just looked back and yelled, ‘C’mon, Doc, there’s wounded in there. Let’s go get them.'”

Hinger, who had retrieved several injured colleagues already, got close enough to the powerfully built officer to see a sniper’s bullet fell him. The medic lifted Holleder’s head into his arms and watched the big man die. The father of four young daughters was 33.

This afternoon’s Army-Navy game at Lincoln Financial Field will mark the 50th anniversary of that 14-6 Cadets victory that Holleder led and inspired. That game and his heroic death have combined to make Holleder, little known beyond West Point, an Army legend.

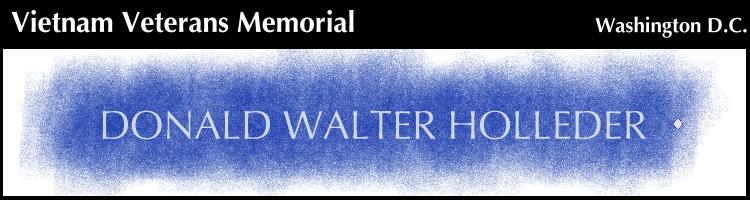

His name, which can be found on an Arlington National Cemetery gravestone and on Panel 28, Row 25, of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, lives on elsewhere, too. The military academy’s athletic center bears his name. So does a plaque in the National Football Foundation’s Hall of Fame. And the Army football team’s Black Lion Award, presented earlier this week to backup tailback Scott Wesley, honors Holleder and the Black Lions of the Second Battalion who died along with him that distant day.

There is resonance in his story because his final moments – ordering his helicopter pilot to land, jumping from the craft and sprinting toward his wounded colleagues – so closely mirrored the attributes he displayed on the football field that season a half-century ago.

“People just expected Don Holleder to excel,” said Jim Shelton, a retired Army major who served with him in Vietnam and scrimmaged against him at West Point as a Delaware linebacker. “And he expected the same thing of himself.”

Tall, handsome, a three-sport star at Aquinas Institute in Rochester, New York, crew-cut Don Holleder was an all-American boy and an all-American end for a 7-2 Army team that had the nation’s leading offense in 1954. But quarterback Pete Vann was gone in 1955 and coach Earl “Red” Blaik needed a replacement. He turned, almost inexplicably, to Holleder.

The 6-foot-2 200-pounder had never played in the backfield. He understood that the switch would cost him his all-American status and expose him and his coach to criticism. But, after sleeping on Blaik’s unusual proposal, Holleder agreed.

“He understood self-sacrifice,” said Hugh Wyatt, a high school football coach in Camas, Wash., who once was the personnel director for the World Football League’s Philadelphia Bell and who conceived the idea for the Black Lion Award. “In Vietnam and on the field he was willing to do whatever was best for his team.”

The criticism came. Heading into the season-ending November 26 game with Navy, Army was a disappointing 5-3. Blaik was ridiculed for the peculiar move and Holleder, who threw just 63 passes the entire season, completing only 22, was labeled one-dimensional.

Holleder himself heard fellow Cadets criticizing his play and even Lieutenant General Blackshear Bryan, the academy superintendent, made it a point to tell Blaik how much heat he was getting over the quarterback.

“He couldn’t throw,” Shelton recalled. “He would just roll left or roll right and run it himself. But he was a load to bring down. Tackling him was like trying to tackle a horse. And after you did, he got up kicking and swinging.”

He was someone, as author David Maraniss noted in his book, They Marched Into Sunlight, which focuses on that 1967 Vietnam battle, “people either loved or hated.”

But Blaik demanded and prized toughness above all else. He stuck with his tough QB.

“Holleder was a natural athlete, big, strong, quick, smart, aggressive, a competitor,” Blaik wrote in his 1960 autobiography. “I knew he could learn to handle the ball well and to call the plays properly. Most important, I knew he would provide… leadership.”

Navy, with a 6-1-1 record and the nation’s top passer, future Midshipmen coach George Welsh, was a clear favorite when they arrived in Philadelphia.

The night before the game, Blaik gathered his team at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel and told them he was wearying of those long postgame walks to shake hands with winning coaches.

“That walk tomorrow, before 100,000 people, to congratulate [Navy coach] Eddie Erdelatz would be the longest walk I’ve ever taken in my coaching life,” he said.

There was silence in the room. Then Holleder spoke. “Colonel,” he said, “you’re not going to have to make that walk.”

No one in a sun-splashed Municipal Stadium crowd of 102,000 – President Eisenhower didn’t come, but Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren was among the 37 trainloads of spectators who arrived in Philadelphia for the game – was surprised when the Midshipmen took the opening kickoff and drove 76 yards for a touchdown and a 6-0 lead.

Holleder and Army couldn’t do anything offensively and Navy looked to add to its advantage. But it was Holleder – in those days of no-platoon football, the offense played defense, too – who kept them from doing so.

He knocked down a fourth-down pass to end one Navy drive and forced a fumble at Army’s 13 to stop another.

In the second half, with Holleder now running the ball and confidently directing the offense, Army scored twice to take a 14-6 lead that held up.

Afterward, General Douglas MacArthur was so ecstatic that he sent a gushing telegram to Blaik.

“No victory the Army has won in its long years of fierce football struggles has ever reflected a greater spirit of raw courage, of invincible determination, of masterful strategic planning and resolute practical execution.”

A week later Holleder became the only quarterback to appear on Sports Illustrated’s cover following a game in which he failed to throw a single completion. One of his two passes was intercepted and the other should have been.

After graduating in a 1956 academy class that included General Norman Schwarzkopf, Holleder went on to an outstanding career as an infantry officer and even served for three years as an assistant football coach at West Point.

On October 17, 1967, as he sat in a helicopter helplessly observing the closing stages of a North Vietnamese ambush that would kill 58 Americans, Holleder was, in Maraniss’ words, “an untamed mustang.”

He badgered his commanding officer until Holleder finally got permission to land. The major leapt from the chopper, grabbed a .45 pistol and some nearby soldiers, including Hinger, and made for the bloody jungle.

“He was running hell-bent when automatic-weapons fire got him,” said Hinger, who like Shelton is retired and living near Sarasota, Florida. “Then, a moment or so later, he died in my arms. It’s funny, I only knew Don Holleder for about two minutes. But that was long enough to know what kind of man he was.”

Holleder posthumously awarded Distinguished Service Cross

Courtersy of Stars and Stripes

Published: April 28, 2012

Pat Tillman and Don Holleder played football well enough to draw the interest of NFL teams. Like Tillman, Holleder – a generation earlier – opted for military service, though Tillman did play in Arizona for a few years. Both died in the line of duty in a far away land.

Though it has been more than four decades since Holleder’s death, the Army hasn’t forgotten his service or sacrifice either. On Friday, the Army posthumously awarded Holleder the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest combat award for a servicemember, the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle reports.

At the time of his death, Holleder was a major serving in Vietnam. On October 17, 1967, he was fatally shot by a sniper while leading an effort to assist 142 soldiers being fired on by an overwhelming enemy force. The paper, quoting from the citation, said that under “intense sniper fire” Holleder led an effort to evacuate the wounded, “had a stabilizing effect on his men and was instrutmental in saving many lives.”

Holleder was promiently mentioned in a Stars and Stripes article in January 1964 while serving as a company commander in Korea. Robert F. Kennedy, then the U.S. Attorney General, was in south Korea visiting with U.S. forces when their paths crossed.

Kennedy, who refered to Holleder as one of his heroes, posed with the company commander for pictures. Like Tillman, Holleder’s decision to choose the military over football had drawn great interest. An All-American football player at West Point in 1954, Holleder rejected an offer from the New York Giants to pursue a military career.

In the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle article, a former West Point teammate of Holleder’s described the former quarterback as a leader.

“Don was one of the most aggressive football players I’ve ever laid my eyes on,” the paper quoted Bill Cody as saying at Friday’s ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery. Holleder was “one of those guys who couldn’t think of anything but winning.” Cody added that Holleder “was truly ambitious in the sense of doing the right thing – not ambitious in terms of taking credit.”

Friday’s ceremony was attended by former West Point classmates, such as Cody, Army veterans and three of his four daughters.

28 April 2012:

A generation before Pat Tillman made headlines in 2002 by giving up a professional football career to serve in the Army, there was Don Holleder.

Holleder, a former Rochester, New York-area high school athlete for Aquinas Institute who went on to become a 1954 All-American football player at West Point and chose a military career over the New York Giants, which wanted to draft him.

Both men died in the line of duty.

Tillman died in 2004 in Afghanistan, a victim of what the Pentagon eventually said was friendly fire.

Holleder was killed by an enemy sniper October 17, 1967, during the Battle of Ong Thanh northeast of Saigon.

Both were posthumously awarded a Silver Star.

On Friday, more than 44 years after Holleder’s death, three of his four daughters were on hand at his gravesite in Arlington National Cemetery as the military again honored their father’s bravery, this time with the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest combat award.

Representative Jack Kingston, R-Georgia, presented Holleder’s daughters with the award to recognize “extraordinary heroism in action” and the “complete disregard for personal safety” their father demonstrated.

Holleder led three volunteers to assist 142 soldiers being fired on by 1,400 enemy troops protected by underground bunkers.

“When the intense sniper fire impeded the evacuation of the wounded, Maj. Holleder unhesitatingly moved forward to reconnoiter the evacuation route,” the citation stated. “He refused to seek cover from the deadly volleys of insurgent sniper fire and continued to assess the enemy situation until he was mortally wounded from the heavy ground fire. His tremendous courage and poise in the face of overwhelming odds had a stabilizing effect on his men and was instrumental in saving many lives.”

Friday’s gravesite ceremony was attended by about 70 people, including West Point classmates and Army veterans who had known Holleder in Vietnam.

Bill Cody of Vienna, Virginia, was among West Point’s quarterbacks when coach Earl Blaik decided to make Holleder, then a tight end, the team’s No. 1 quarterback. Cody never had a problem with the move.

“What Blaik was looking for was leadership, and Don was a leader,” Cody said. “That’s what he got. Don was one of the most aggressive football players I’ve ever laid my eyes on. And one of those guys who couldn’t think of anything but winning … He was truly ambitious in the sense of doing the right thing, not ambitious in terms of taking credit.”

The U.S. Military Academy’s indoor basketball and hockey arena is named in honor of Holleder, and until 1985, a stadium in Rochester used by the Aquinas Institute bore his name. The site of the former stadium, now an industrial park, still uses his name.

Terry Tibbetts, who wrote a biography of Holleder published last year, said Holleder’s death resulted from a “poorly planned battle” in which 58 soldiers were killed and 75 were wounded.

Retired Lieutenant Colonel Albert Welch told participants at Friday’s ceremony that the night before the battle in which Holleder died, the military commanders discussed bombing the area where the enemy was located.

Welch, a lieutenant at the time of the 1967 battle, said the saturation bombing never occurred.

He said he spoke to Holleder the night before his death.

“Major Holleder and I had a wonderful talk,” Welch said, noting that Holleder talked soldier-to-soldier to him, disregarding their difference in rank.

Susan Connors, one of Holleder’s daughters, said it was remarkable to her that so many of her father’s friends and former classmates would remember him so vividly more than 40 years after his death.

Holleder’s oldest daughter, Stacy Jones, said that if her father had survived, “I don’t think he would have looked for an upgrade of an award.

“But it was explained to me that this was very important to the Army and also to the corps of cadets at West Point,” she said. “This is a tribute to him and also to those who won’t let him be forgotten.”

Another of the four daughters, Katie Fellows, visits West Point every January to present the Black Lion Award to one of the team’s football players. The criteria: leadership, courage, devotion to duty and self-sacrifice.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard