From a press report: 2 February 2002:

The Army that once cast Mary Bender aside drew her back Friday for a final martial embrace.

Once, the late Roseville resident interrogated Viet Cong prisoners.

Later, she was forced out of uniform because of pregnancy. Now, her ashes rest at Arlington National Cemetery in a bittersweet place.

“She’s probably looking down and really happy,” her son, Joshua Bender, said Friday morning, after the creased thunder of a full-honors Arlington service. “I couldn’t ask for more respect.”

Except that Bender believes his mother deserved a full burial at Arlington. Instead, her inurned ashes were placed in the cemetery’s Columbarium. It is striking in its own way, an open-air network of vaults, but it is not quite what Mary Bender’s only child wanted.

But for Mary Bender’s pregnancy and unwanted discharge, her son believes she would have spent a full career in the Army. That would have ensured her an Arlington burial plot, instead of the Columbarium niche granted by virtue of her nine years of service. And but for the Army’s policies of the time, Bender said he believes his mother would have received benefits that might have eased her life and his.

“Now that we are past my mother’s life, there are some rights we have to look at,” Bender said.

He means compensation, financial and otherwise. He would like legislation, if he could find the right sponsor.

So would an untold number of other women whose military lives were disrupted. For these women, forced from service before pregnancy policies changed in the mid-1970s, Mary Bender’s sorrowed life has become a rallying point.

“This woman was phenomenal,” said Modesto resident Patsy Paluso, a security supervisor at E.&J. Gallo Winery. “And then, she wasn’t good enough for the military when she became pregnant. And that’s a sad thing.”

Paluso can relate. She enlisted in the Army in June 1970, after attending Modesto High School. She was training in air traffic control in Alabama, where she met a helicopter pilot. He was a Warrant Officer. She was a Private First Class, and she thought it was love.

She became pregnant, and the man left. He did not want to mess up his high-flying career. She was ushered into her superior’s officer, who told her she would be honorably discharged whether she liked it or not.

“I said, ‘I like the military, what are my options?'” Paluso recalled. “And they said, “None.'”

Thrown back into civilian life, Paluso resorted to public assistance for a time. She married, had several other children, became single again and in time returned to Modesto.

After a while, she started tracking down friends from basic training. That was how she connected with Caroline Tyler, a veteran from the suburbs of Milwaukee, who had begun prowling the Internet.

Tyler was forced from the Army in 1970 after she became pregnant, and she found common cause with Paluso. They formed an organization they call the Fifth Amendment Sisters.

The name honors a 1976 appellate court ruling that struck down a Marine Corps regulation mandating discharge of pregnant Marines; the regulation, judges said, unconstitutionally presumed that pregnancy made the woman permanently unfit for duty.

So far, Tyler and Paluso say they have identified more than 1,000 women who have gone through the same thing.

“I call them my girls, my ladies,” Tyler said. “My sisters.”

Tyler and Paluso have never met in person; theirs, so far, is an Internet and telephone relationship. But Friday, having overcome a Midwestern snowstorm, Tyler showed up at Arlington for Bender’s service. Paluso wanted to come but had to be with one of her daughters in Kentucky.

So Tyler stood, on an unseasonably warm February morning, in solidarity with another woman she had never met. Mary Bender’s story, though, was one that she had taken to heart after Mary’s son discovered her through the Internet.

“I feel like I know him,” Tyler said before the service.

A seven-man rifle team fired off three cracking volleys. An unseen bugler played taps. The Army band played “America the Beautiful” incomparably.

Arlington cemetery Superintendent Jack Metzler, who had denied Josh Bender’s request for an exemption to the burial requirements, made an atypical appearance at the service, one of about 25 held daily at the cemetery.

This much, Bender had earned.

A warrant officer in the Women’s Army Corps, Mary Bender served three tours in Vietnam. There, she conducted polygraph exams and aided sensitive counterintelligence efforts. She also became romantically entangled with a married

co-worker.

He stayed in. She was forced out, and in a tough life marred by drinking and occasional homelessness, she raised Joshua by herself.

Joshua’s father, Mary Bender’s wartime lover, did not attend the service. But there were, among the two dozen people present, others who knew her or who had come to know her story.

“Mary Bender,” said Lieutenant Colonel James May, an Army chaplain, “made a difference in the world.”

Son wins mom a place in Arlington

Pregnancy had forced the decorated Vietnam War veteran out of the military.

She was a decorated Vietnam War veteran who was forced to leave the military after becoming pregnant out of wedlock. As a single mother, she worked as a private eye, then battled alcoholism, depression and homelessness for years.

This week, Mary V. Bender of Roseville will be inurned at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia with full military honors. At her funeral will be her only son, Joshua Bender, and a small circle of former military women whom she never met. These people, who met online after Mary’s death, fought hard to ensure that Bender will be memorialized among the nation’s heroes. They wanted the former espionage agent’s life, which ended January 10, 2002, in a stark Palo Alto, California, hotel room, to be honored.

But despite their efforts, Bender won’t be buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Her cremated remains will be inurned there — a slightly lesser distinction. In the end, the rules that forced Mary Bender from the military in 1972 served to block her full entry into Arlington in 2002.

For Joshua Bender, the fact that his mother’s name will be etched in a wall at the cemetery is still a victory.

“She always told me that she would be there,” he said. “To her, that would be the final recognition.”

In the days following his mother’s death, Joshua Bender lugged a black backpack over his shoulders like a dead weight. In it, he carried his mother’s military files, which chronicled Mary Bender’s nine years and nine months in the U.S. Women’s Army Corps.

The files included his mother’s enlistment papers, stellar performance reviews and documentation of the bronze stars and other commendations she received while serving in the WAC.

Joshua Bender discovered the files in the back of his mother’s car a few days after her death. He hoped the mildewy paperwork, which carried the dust of 30 years, would gain his mother entry into Arlington National Cemetery.

The files contain enlistment papers proving Mary Bender had repeatedly volunteered for military service during the Vietnam War. She was one of roughly 11,000 women who served in uniform in the war.

Her performance reviews provide a picture of the duties the young warrant officer performed.

“Miss Bender has energetically and tirelessly given of herself … in the sensitive counterespionage operations of the 66th Military Intelligence Group,” reads a review dated August 3, 1967.

But a short letter, written on Valentine’s Day 1972, ended all the military service documentation.

“Inclosed (sic) is the medical certificate of pregnancy … ,” the letter read. “Recommend Honorable Discharge Certificate, DD Form 356A. … It is my understanding that this will be an involuntary separation.”

Mary Bender was involuntarily discharged from the military for being pregnant out of wedlock, as many women were at that time. Under military regulations, pregnancy was considered a sickness “not in the line of duty.” Joshua Bender believes his mother’s involuntary discharge was a slap in the face from which she never recovered.

“She was betrayed, and she felt betrayed,” Joshua Bender said.

But she remained a patriot.

“She still had such love for the Army … and the ideals of our country,” said Mary Bender’s nephew, Chris Anderson of Granite Bay.

After receiving word that his mother had died of respiratory problems, Joshua Bender set out to right what he believed was a wrong.

He left his home in New York to plan his mother’s funeral from his aunt’s home in Roseville.

Mary Bender, who grew up in Southern California in a family of 12 children, had been living in Roseville with her sister intermittently for the past eight years. When her nomadic streak flared up, she would take to living in hotels near a veterans hospital in the Palo Alto area. She was on one of those streaks when she died.

As Joshua Bender made calls to have his mother’s body moved to Arlington, his plans hit a snag. Arlington officials said Mary Bender was ineligible for burial at the historic cemetery because she didn’t have enough time in service. Nor had she earned any of the five medals that make one eligible for Arlington burial, one of which is the Silver Star, given for bravery.

Her son was outraged. He believed his mother would have had enough service time had she not been involuntarily discharged for pregnancy.

“She would have stayed in the military until her dying day,” Joshua Bender said, adding that his mother had hoped to be like her father, a U.S. Merchant Marine who spent his entire life in the service.

Joshua Bender also believed his mother should have been awarded a Silver Star, one of the medals that would have qualified her for an Arlington burial. The family says she deserved it for helping to keep hold of a military post being overrun by the Viet Cong.

Mary Bender’s military files back up the claim.

To get his mother into Arlington, Joshua Bender started out by cruising Web sites devoted to military women. Jumping from link to link, the 29-year-old theater set designer found a group called the Fifth Amendment Sisters.

Headed by Patsy Paluso of Modesto and Caroline Tyler of Milwaukee, members of the Fifth Amendment Sisters were seeking to find women who had been involuntarily discharged from the military for pregnancy.

Tyler said the group is working to get a bill passed through Congress that would give women back pay and other benefits they lost when they were involuntarily discharged. They also hope to have Mary Bender awarded the Silver Star posthumously.

“It was unequal, unfair and unconstitutional,” said Tyler, whose military service also was ended because of pregnancy. “It disgraced our military women and did not give them equal treatment.”

Female military personnel could be granted waivers to the pregnancy discharge rule, and many were. But many others never were advised such waivers existed, veterans’ advocates claim. Individual commanding officers essentially were left to determine who would be discharged for pregnancy and who would not, Tyler said.

All branches of the military dropped the pregnancy discharge policy in 1975. An appeals court later ruled the practice unconstitutional.

Paluso, 50, was discharged from the WAC in 1971 for pregnancy. She said she never was advised she could appeal the decision.

“I was told ‘You’re pregnant, you’re out the door,’ ” said Paluso. “I asked about waivers and I was told, ‘No.’ ”

Determined that Mary Bender should be buried at Arlington, Tyler, Paluso and Joshua Bender sent missives to officials at the cemetery, the Department of Veterans Affairs and elected officials across the country.

Jack Metzler, superintendent of Arlington National Cemetery, said it didn’t matter that Mary Bender’s discharge later was ruled unconstitutional.

“That was the Army’s rule at that time,” Metzler told The Bee. “That’s not my issue.” Officials at the Department of Veterans Affairs in Washington, D.C., said they had no jurisdiction over Arlington burials.

Ultimately, Mary Bender’s advocates opted to have her inurned at Arlington, something offered to anyone who served any length of service in the military.

Arlington officials agreed to give Mary Bender a full 21-gun salute and the honor of a military band. Tyler and Paluso plan to attend the service Friday.

“There are gives and takes in life,” said Joshua Bender. “With the amount of time we spent trying to fight on this, Mom’s dignity kept going down by not giving her a proper burial.”

Joshua Bender knows there were many things in his mother’s life that never made it into her military files.

There were the years after Mary Bender’s discharge, when she toiled as a single mother running her own private investigations firm in Alexandria, Virginia. The Bender family, which consisted only of Joshua and his mother, had a house then, and cars, too. Those were the sober years, when Mary Bender’s depression and alcoholism would go into a kind of remission. Those were the years Mary Bender coached Little League and had a new joke to tell nearly every day.

“The sober years were definitely the best years,” said Joshua Bender.

But the business failed in 1984. Mary’s depression and alcoholism worsened. The Benders lost their home. At 13, Joshua Bender moved in with friends. When she wasn’t staying with family members, Mary Bender lived on the streets and in hotels, refusing help from her son and others. She lived that way until the day she died.

VA officials estimate about 3 percent of homeless veterans are women.

There’s no mention of Joshua Bender’s biological father in the files, either. Joshua said he married another woman.

And there’s no mention of Mary Bender’s “demons,” as her family called them: her horrific memories of Vietnam, such as the bombing of Saigon during the infamous Tet offensive of 1968 and the leveling of an orphanage there.

The “demons” often visited Mary Bender in her dreams, her family members said.

There’s no paperwork on that.

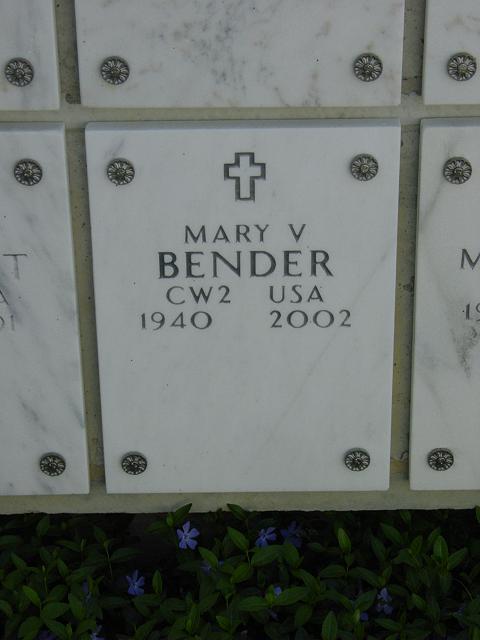

But Friday, these words will be etched in stone, not paper, at Arlington National Cemetery: “Mary V. Bender 1940-2002.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard