March 24, 2005, 7:58 a.m.

The Last Cold War Casualty

The heroic story of Major Nicholson.

Courtesy of the National Review

Twenty years ago today, Army Major Arthur D. “Nick” Nicholson drove into East Germany to survey Soviet military activity. It was a bright Sunday morning, and he was about to become the last American to die in the Cold War.

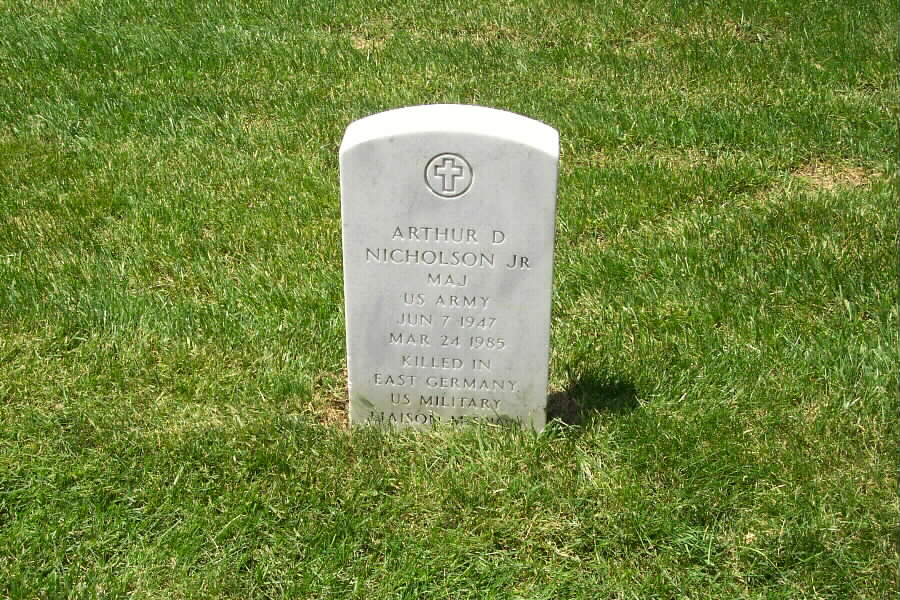

Relatively few people have heard of Nicholson, even though his killing dominated newspaper headlines around the world for several tense days two decades ago. A handful of people won’t ever forget him: A small band of former comrades gathers at his Arlington National Cemetery each spring. They’re meeting again this Saturday. Today, at the site of his death near Ludwigslust, the Allied Museum will join Nicholson’s widow Karyn and his former commander, Major General Roland Lajoie, in dedicating a memorial stone.

I wrote about Nicholson’s story in National Review last year. Since then, the Pentagon has made available a large batch of documents on the U.S. Military Liaison Mission, which is the organization Nicholson was serving when he died. Many of these papers describe in detail what happened on his final day. It would be an exaggeration to say they contain shocking new revelations, but they do deepen our understanding of what happened on March 24, 1985.

That morning, which was a Sunday, Nicholson headed into East Germany with his driver, Army Staff Sergeant Jessie Schatz. As members of the USMLM, Nicholson and Schatz were basically licensed spies. Their organization was a holdover from the Second World War, when the Allies assigned representatives to work with each other in Germany’s various zones of occupation as Hitler’s minions disarmed. These special liaison units did not disband with the onset of the Cold War. Instead, they were given something of a carte blanche to roam around the countryside and observe military activity. The Americans, British, and French had soldiers assigned to East Germany, and the Soviets had teams tasked to West Germany.

This awkward arrangement remained in place because both sides found it a useful way of collecting information on the opposition’s troop movements and military hardware. Yet there were enormous tensions, and these always carried the potential of deadly violence.

Sometime in the afternoon, Nicholson and Schatz followed a convoy of Soviet tanks returning from target practice. It was a typical USMLM activity. Nicholson was probably counting the tanks and studying their exteriors. A little while later, the Americans broke off and approached a tank shed. They thought they were alone. The USMLM’s 1985 unit history describes the scene and what happened next:

This facility served the Independent Tank Regiment of 2 Guards Tank Army. Known to be frequently guarded under normal conditions, it had a varied history of occasionally violent reaction. Thus, the tour [i.e., Nicholson and Schatz] entered the area with considerable caution, stopping in the forest to watch and listen at intervals as they did so. SSG Schatz, who had just visited the area a few days prior pointed out an area which had been recently occupied, but the Soviets had departed it. The tour then approached the sheds, photographed signboards displayed nearby, and positioned the vehicle to permit the tour NCO [Schatz] to pull security while the tour officer [Nicholson] checked for armor.

Unbeknownst to the tour, and despite its best efforts at observation, a sentry remained undetected, concealed in the adjacent woods. According to information obtained later, he had been walking near his post on the far side of the sheds as the tour approached. Hearing the vehicle, the Soviet soldier made his way through the flank of the range to a position about 50 meters behind the tour; SSG Schatz noticed him just before he opened fire. The Soviets claim that the sentry issued a challenge in two languages (Russian and German), fired a warning shot into the air, then shot to disable. This is simply not true. SSG Schatz, a native German, heard no challenge in any language. The sentry’s first shot whizzed narrowly over the heads of the tour; it was not a warning, but a miss. And one of the two remaining rounds struck MAJ Nicholson, by this time running back to the tour vehicle, near his center of mass: the upper abdomen. SSG Schatz shouted a warning as the first shot resounded — too late to help. He then slammed the hatch shut, started the car, and threw it into reverse to reach MAJ Nicholson. Hit by one of the shots, Nicholson groaned, fell, called to Schatz, and promptly lost consciousness. The tour NCO sprang from the vehicle to administer first aid, but the sentry refused to permit him to do so. Using sign language, SSG Schatz communicated his intent to the Soviet and took a step toward the fallen officer. The sentry, who had held Schatz at gunpoint the entire time, then shouldered his AK-47, took aim at Schatz’s head, and motioned him back to the vehicle. Seeing the futility of further action and the hopelessness of the situation, SSG Schatz complied. He secured and covered the tour equipment, check to be sure the doors were locked, and waited. Shock set in quickly. …

Over the next three hours many Soviet officers and soldiers arrived to secure the area, collect data, and investigate the situation; considerable confusion reigned. Yet no one, including the obvious medical personnel, rendered even rudimentary first aid. Finally at 1605A (one hour, 5 minutes after the shooting) an unidentified individual in a blue jogging suit took MAJ Nicholson’s pulse, which had ceased. The protracted failure to provide or even permit any medical attention at all ensured that the wound proved fatal.

An international furor ensued, as the Americans and Soviets traded accusations. The United States demanded an apology and compensation for Nicholson’s wife; the USSR claimed, outrageously, that Schatz had refused to leave his car to help his companion. After a while, the controversy subsided and the Cold War plodded on for a few more years.

One thing is not in dispute: Arthur Nicholson fell a hero, the last American casualty of the Cold War. “Nick did not want to die, and we did not want to lose him,” said his widow. “But I know that he would lay down his life again for America.”

E-Mail: March 2005:

This message announces and provides brief organizational detail for the TWO commemorative ceremonies that will mark the 20th anniversary of the shooting by a Soviet sentry of Major Arthur D. Nicholson, Jr. in Ludwigslust.

1. Ludwigslust. As Dr. Helmut Trotnow has announced separately, the Allied Museum-Berlin will conduct its ceremony in Ludwigslust at 1100 hours (local time) on 24 March (Holy Thursday). The program will center on the unveiling of a memorial stone at a turnoff from the B-191 onto the former subcaliber range. Local authorities from the Bundeswehr, Ludwigslust and Karstaedt will participate; circumstances permitting, General Lajoie hopes to do so as well.. Subject to ongoing coordination, US Embassy-Berlin and the German Government may also send representation.

2. Arlington National Cemetery . This year, the annual graveside ceremony in Arlington will occur at 1100 hours (local time) on 26 March (Holy Saturday). Those desiring to participate are requested to gather directly at Nick’s grave, which is #171 in Section 7A.

Angel Gonzalez

U.S. Military Liaison Mission Association

A non profit Veterans Association

Contemporary press reports: March 1985

Mar 30, 1985: Vice President Bush called Major Arthur D. Nicholson Jr. “an outstanding officer murdered in the line of duty,” honoring him during a brief ceremony yesterday marking the return of the body of the Army officer slain by a Soviet guard in East Germany.

“We can only hope that the Soviet Union understands that this sort of brutal international behavior jeopardizes directly the improvement in relations which they profess to seek,” Bush told a crowd of about 150 military officials, reporters and others gathered at Andrews Air Force Base to meet the plane carrying Nicholson.

Nicholson, 37, was shot to death last Sunday afternoon by a Soviet sentry while on a monitoring mission. He was one of 14 officers assigned to East Germany under a 1947 US-Soviet agreement that provides for the exchange of intelligence-gathering missions in East and West Germany. The Soviets have maintained that Nicholson was trying to take photographs in a clearly marked restricted area, a charge the State Department denies. Earlier in the week, US officials publicly referred to Nicholson’s death as “murder”, but in the last couple of days their statements had been less critical. State Department officials said there is a possibility Secretary of State George P. Shultz and Soviet Ambassador Anatoly F. Dobrynin will meet today to discuss the case.

Nicholson’s flag-draped coffin was accompanied on the Air Force flight from Frankfurt yesterday by his wife, Karyn, his 9-year-old daughter, Jennifer, and the 13 other members of the US liaison team. “It was their desire to come home to attend his funeral,” said US Army Lieutenant Colonel Miguel Monteverde said of the officers. “. . .Right now their function in East Germany is not being performed.”

Under dark, opalescent skies, Nicholson’s widow greeted Vice President and Mrs Bush and moved down a line of relatives, friends and officers, shaking hands with some and hugging others. Her daughter, holding a yellow-haired Cabbage Patch doll, waited with bowed head beside Nicholson’s parents from Redding, Connecticut. Nicholson’s fellow liaison officers stood at attention beside the silver hearse that held his coffin. Sgt Jessie Schatz, who was on patrol with Nicholson when the shooting occurred, stared straight ahead. Schatz told officials earlier this week that Nicholson cried out, “Jess, I’m shot.” He also said Soviet soldiers prevented him from administering first aid.

Nicholson will be buried at 1 p.m. today at Arlington National Cemetery.

March 31, 1985: Family, friends, colleagues and top Army officials gathered yesterday in a military chapel at Fort Myer to honor Major Arthur D. Nicholson Jr. and eulogize him as a man who had volunteered for a stressful assignment because he wanted to be on “the cutting edge.”

Nicholson, 37, a liaison officer to East Germany, was shot and killed by a Soviet sentry near a garage-like storage shed one week ago. Nicholson, whose hometown was West Redding, Connecticut, had been attached to the 14-member liaison mission in Potsdam since 1982.

As several hundred people honored Nicholson at a service in Fort Myer’s Memorial Chapel and a military burial in Arlington National Cemetery, Secretary of State George Shultz and Soviet Ambassador Anatoliy Dobrynin met at the State Department and agreed on discussions to prevent similar incidents.

In the chapel, family, friends and colleagues sat silently as the muffled beats of a drum corps outside signaled the arrival of the major’s flag-draped casket. Colonel Roland LaJoie, commander of the liaison mission, recalled Nicholson as a man who “not only passed the tests, he set the standards.” Nicholson was “my officer, my professional colleague and, most importantly, my personal friend,” LaJoie said. “I was the last of us to see Nick alive and the first to see him dead.” LaJoie praised Nicholson’s heroism and decried the circumstances of his death. “It was not a battle, it was not a fair fight; he was unarmed, in uniform, in broad daylight . . . . ” And he stressed that Nicholson believed in the value of his work. “He constantly sought ways to increase contacts with Soviet officers so we could get to know each other better. Nick immensely enjoyed what he was doing, and I can tell you unequivocally, he was very good at it. “He wanted to be out there, and he needed to be out there, close to what he considered the cutting edge,” LaJoie said.

Following the chapel service, the funeral procession wound slowly through the cemetery. The horse-drawn caisson bearing Nicholson’s casket came to rest near the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. More than 200 people ringed the grave site under ashen skies, listening to the music that resounded for minutes before members of the US Army Band marched into view. Six white horses pulling the caisson halted near the gravesite, and Nicholson’s family stood behind–his parents, his wife Karyn and his 9-year-old daughter Jennifer, who clutched a sprig of flowers in one hand and a doll in the other. Riflemen fired three volleys into the chilly air, and a single bugler played Taps.

After a brief, quiet service, Deputy Secretary of Defense William Howard Taft IV presented flags to Nicholson’s wife and father; Army Secretary John O. Marsh Jr. gave the Legion of Merit award, and Army Chief of Staff General John A. Wickham presented The Purple Heart. Nicholson’s family rose and, one by one, placed roses on his casket. His daughter, then his wife, bent to kiss the lid. The funeral party dispersed quickly, and a few people drifted down the hillside from the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to stare at the casket, the mounds of flowers and the empty chairs.

Born: June 7, 1947. Killed by Russian Border Guards, East Germany, March 24, 1985. He is buried in Section 7-A of Arlington National Cemetery.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard