Courtesy of the United States Marine Corps:

Marines And The O.S.S.-WW II

Colonel Peter J. Ortiz, USMC

One of the most decorated Marine officers of World War II, Colonel Peter Ortiz served in both Africa and Europe througout the war, as a member of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

Although born in the U.S., he was educated in France and began his military service in 1932 at the age of 19 with the French Foreign Legion. He was wounded in action and imprisoned by the Germans in 1940. After his escape, he made his way to the U.S. and joined the Marines. As a result of his training and experience, he was awarded a commission, and a special duty assignment as an assistant naval attache in Tangier, Morocco. Once again, Ortiz was wounded while perfoming combat intelligence work in preparation for Allied landings in North Africa.

In 1943, as a member of the OSS, he was dropped by parachute into France to aid the Resistance, and assisted in the rescue of four downed RAF pilots. He was recaptured by the Germans in 1944 and spent the remainder of the war as a POW.

Ortiz’s decorations included two Navy Crosses, the Legion of Merit, the Order of the British Empire, and five Croix de Guerre. He also was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by the French.

Upon return to civilian life, Ortiz became involved in the film industry. At the same time, at least two Hollywood films were made based upon his personal exploits. He died on 16 May 1988 at the age of 75.”

Colonel Ortiz was born in New York City but educated in France where he left school before graduation to join the French Foreign Legion. He was said to be the youngest sergeant in the history of the Legion. He was wounded in action between the Legion and Germans in 1940, then imprisoned in a concentration camp in Austria.

After escaping and then making his way to the U.S. and joining the Marine Corps in June 1942, he was commissioned in August 1942 and then commissioned a Captain in the Marine Corps Reseve in December 1942. He was assigned to North Africa as an assistant naval attache where he organized a patrol of Arab tribesmen to scout German forces on the Tunisian front. He was asigned to the OSS after recovering from wounds suffered in Tunisia.

Captain Ortiz had reported back to Marine Corps Headquarters in April of 1943, and the following month joined the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a secretive organization and predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). He was a graduate of both the Legion’s and Marine Corps’ parachute schools. Having lived in France he was fluent in that language; he also spoke nine other languages and was fluent in five.

He parachuted into France on January 6, 1944, assigned to help organize and lead elements of the French underground forces known as the “Maquis.”

The Leatherneck magazine of January 1991, reports that:

In the course of his duties he began frequenting a nightclub in Lyons that catered to German officers. This enabled Ortiz to gain much information regarding German activities in the area, which he turned to good use against the Germans. This Marine had worn his Marine uniform when leading Maquis groups in raids. To have an Allied officer leading them bolstered their morale immensely, especially when the uniform bore such impressive decorations.

One night, while Ortiz sat with the German officers at the club in Lyons, an enemy soldier damned President Franklin Roosevelt. He then damned the United States of America. And then, for whatever reason, he damned the United States Marine Corps (Ortiz later wrote that he “could not, for the life of me, figure why a German officer would so dislike American Marines when, chances were, he’d never met one.”)

Perhaps Ortiz was bored. Perhaps he……he excused himself from the table and returned to his apartment where….changed into the uniform of a U.S. Marine….he then shrugged into a raincoat and returned to the club….he ordered a round of drinks … refreshments were served…. removed his raincoat and stood brandishing his pistol. “A toast, he said, beaming, respendent in full greens and decorations, “to the President of the United States!” As the pistol moved from German officer to German officer, they emptied their glasses. He ordered another round of drinks and then offered a toast to the United States Marine Corps! After the Germans had drained their glasses, the Marine backed out, pistol levelled at his astonished hosts. He disappeared into the rainy, black night.

The train approached. The explosive device was detonated …. the Marqis opened up …. Grenades were tossed. Ortiz waited for the firing to subside, then stood in full view in his Marine Corps uniform and ordered the Maquis to withdraw …. leaving 47 Germans dead and many others wounded. Not a Maquis was lost. His adventures were numerous…”

–Leatherneck, January 1991

Ater the war, Colonel Ortiz worked with director John Ford, a former member of the OSS himself.. Two movies were produced depicting the exploits of Ortiz. They were, “13 Rue Madeleine,” with James Cagney, etc., and “Operation Secret,” with Cornel Wilde, etc. Ortiz also had small parts in such films as, “The Outcast,” “Wings of Eagles,” and “Rio Grande.” He also played the part of Major Knott in the film, “Retreat Hell,” a movie about the Marines at the Chosin Resevoir in 1950.

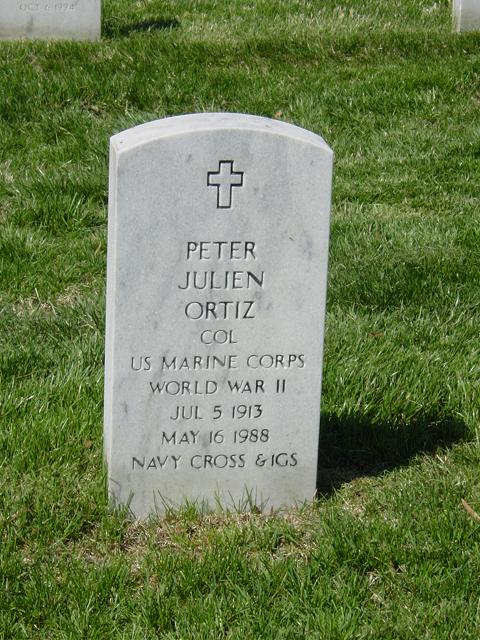

Colonel Peter Ortiz was laid to rest at Arlington National cemetery on May 23, 1988. Prior to burial, the procession was led by the Marine Band in full dress, playing hymns – then a Marine rifle company in full dress, with fixed bayonets – six white horses pulling a caisson with the flag draped coffin and the beautiful black riderless horse with the reversed boot. A Navy Chaplain conducted a short service. Representing the U.S. Marine Corps was General Frank Breth, Director of Intelligence; representing France was Colonel Guy Hussenot; representing England was Captain Jeremy Robbins, of the British Royal Marines.

Peter Julien Ortiz was born in New York on 5 August 1913, of a French father with a strong line of Spanish forebears, and an American mother. Ortiz père was well connected socially and otherwise in France, and had his son, who spent much of his youth in that country, educated there. He was a student at the University of Grenoble when the adventure bug apparently bit him. As I was told recently, “Pete enlisted in the Legion just for adventure. He’d read a lot of romantic tales. He had a Polish girl friend at the time [who was also at Grenoble] and she accompanied him to Marseilles. He enlisted under her name.” His father made an attempt to buy him out, and when he arrived in Morocco to take his son home, “Pete would have none of it,” and he remained in the Legion until 1937. During this time, he rose through the ranks from private to acting lieutenant, and was offered a permanent commission as second lieutenant if he agreed to reenlist for five years and consider eventual naturalization as a French citizen. He turned down the offer and returned to the United States. He was acting lieutenant in charge of an armored car squadron when he resigned. While with the Legion, he fought in a number of engagements in Africa and was wounded in 1933. He was well decorated for this first tour–he received the Croix de Guerre with two palms, one gold star, one silver star, and five citations; the Croix des Combattants; the Ouissam Alouite; and the Medaille Militaire.

He returned to the States and went to California, where his mother lived. He soon became employed in Hollywood as a technical director on military matters. When the war broke out in Europe, Ortiz returned to the Legion. He enlisted in October 1939, got a battlefield commission in May 1940. For his service 1939-1940, he was

decorated with the Croix de Guerre (one palm, one silver star, two citations), Croix des Combattants, 1939-1949. In June 1940, he was wounded and captured. Ortiz was taken when he learned that some gasoline had not been destroyed before his men had withdrawn. He returned to that area on a motorcycle, drove through the German camp, blew up the gasoline dump, and was on his way back to his lines when he was shot in the hip, the bullet exiting his body, but hitting his spine on the way out. He was temporarily paralyzed and easily taken.

He spent 15 months as a POW in Germany, Poland, and Austria. He attempted a number of escapes, and finally succeeded in October 1941. He reached the United States by way of Lisbon on 8 December, and was interrogated by Army and Navy intelligence officers, and was promised a commission. It didn’t come through

immediately. He had been offered commissions by the Free French and the British in Portugal, but he wanted to wear an American uniform. In any case he was not fit for immediate active duty and, besides, wanted to see his mother in California. By June 1942, when nothing further was heard about the commission, he enlisted in the

Marine Corps on the 22d and was assigned to boot camp at Parris Island.

Ortiz was tall, athletically built, handsome, and had a military carriage, which is understandable since he had served over five years with the Legion, and it is also understandable that he stood out from the rest of the recruits in his boot platoon. In addition, he wore his decorations, which caused no little interest by his DIs and the senior officers at Parris Island. Colonel Louis R. Jones, a well-decorated World War I Marine and at this time Chief of Staff at the Recruit Depot, wrote the Commandant of the Marine Corps about Ortiz on 14 July. He enclosed in his letter copies of Ortiz’ citations for the French awards together with Ortiz’ application for a commission. In his letter, Jones wrote:

“Private Ortiz had made an extremely favorable impression upon the undersigned. His knowledge of military matters is far beyond that of the normal recruit instructor. Ortiz is a very well set up man and makes an excellent appearance. The undersigned is glad to recommend Ortiz for a commission in the Marine Corps Reserve and is of the opinion that he would be a decided addition to the Reserve Officer list. In my opinion he has the mental, moral, professional, and physical qualifications for the office for which he has made application.”

On 1 August 1942, Ortiz was commissioned, with a date of rank of 24 July. He was kept at Parris Island for two months as an assistant training officer and then sent to Camp Lejeune to join the 23d Marines, and then, despite the fact that he was a qualified parachutist from his time in the Legion, he was sent to the Parachute School at Camp Lejeune, but not for long. In all, counting his jumps with the Legion, at Camp Lejeune, and with the OSS, he made a total of 154 of all types.

Meanwhile, Headquarters Marine Corps had become very interested in his record, his duty with the Foreign Legion, and the fact that he was a native French speaker, and less so with German, Spanish, and Arabic. On 16 November, Colonel Keller E. Rockey, of the Division of Plans and Policies, sent a memo to Major General Commandant Thomas Holcomb, stating that “The rather unique experiences and qualifications of Lieutenant Ortiz indicate that he would be of exceptional value to American units operating in North Africa. It is suggested that the services of Lieutenant Ortiz be offered to the Army through COMINCH {Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations/Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet].” Colonel Rockey also recommended Ortiz’ promotion to First Lieutenant or Captain. As a matter of fact, he was promoted to Captain from Second Lieutenant on 3 December. On the 21st he left Washington for Tangier, Morocco, where he was assigned duty as assistant naval attaché. That was just a cover.

He was ordered to organize a patrol of Arab tribesmen to scout German forces on the Tunisian front. Major General William J. Donovan, Director of the Office of Strategic Services, forwarded to the Commandant a message from Algiers which read, “While on reconnaissance on the Tunisian front, Captain Peter Ortiz, U.S.M.C.R. was severely wounded in the right hand while engaged in a personal encounter with a German patrol. He dispersed the patrol with grenades. Captain Ortiz is making good recovery in hospital at Algiers. The [P]urple [H]eart was awarded to him.” In April 1943, he returned to Washington to recuperate and in May was assigned to the Naval Command, OSS. In July he flew to London for further assignment to missions in France.

He was to spend most of his time in France in the southeastern region known as the Haute Savoie. In that region is the Vercors plateau, which was of special interest to General Charles de Gaulle, as well as to the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the OSS. Not only were there some 3,000 Free French Maquisards in the area, but it was planned to turn Vercors into a redoubt against which the Germans would attack in vain and which would be a major center of French resistance in the area to be called upon when D-Day arrived. It was vitally necessary to contact and arm this group. To attempt this task, SOE decided to form an inter-allied team consisting of English, French, and American agents. The mission was codenamed UNION and it was to determine the military capabilities of the units reported active in Savoie, Isere, and Drome. The team’s mission was to impress the leaders of such units with the fact that “organization for guerrilla warfare activity, especially after D-Day, is now their more important duty.” The British team member was Colonel H.H.A. Thackwaite, a prewar schoolmaster; the French radio operator was “Monnier,” purportedly the best in the business. Ortiz was the American.

The team dropped into France on the moonless night of 6 January. Per standard SOE practice, they wore civilian clothes, but carried their uniforms with them. Once they linked up with the maquis on the ground, they identified themselves as military men on a military mission. Accordingly, as M.R.D. Foot wrote in SOE in France, they were the first Allied officers to appear in uniform in France since 1940. Thackwaite later wrote that “Ortiz, who knew not fear, did not hesitate to wear his U.S. Marine captain’s uniform in town and country alike; this cheered the French but alerted the Germans and the mission was constantly on the move.”

Parenthetically, I have seen pictures of Ortiz in uniform in France at this time, and was shocked to see that he had removed the grommet from his cap, so that he wore it like Air Corps pilots wore their “30 mission” caps. Incidentally, Ortiz always thought that Thackwaite’s statement that he “knew not fear,” was absolutely ridiculous. Considering all that he had been through with the Legion and now with the OSS, of course he knew fear.

UNION found several large groups of maquisards willing and ready to fight, but lacking weapons. It took the team considerable time to arrange for clandestine arms drops and weapons instruction for the maquis. As Lieutenant Colonel Robert Mattingly wrote in his prize-winning monograph, Herringbone Cloak–GI Dagger:

Marines of the OSS:

“It might be reasonable to suppose that the team remained hidden in the high country, but thiss was not the case. Ortiz in particular was fond of going straight into the German-occupied towns. On one occasion, he strolled into a cafe dressed in a long cape. Several Germans were drinking and cursing the maquis. One mentioned the fate which would befall the ‘filthy American swine’ when he was caught. [The Nazis apparently knew of Ortiz’ existence in the area with the maquis] This proved a great mistake. Captain Ortiz threw back the cape revealing his Marine uniform. In each hand he held a .45 automatic. When the shooting stopped, there were fewer Nazis to plan his capture and Ortiz was gone into the night.

This story has appeared in several forms, but in any case it appears that there was this confrontation, with the Nazis the losers. Ortiz appeared to be truly fearless and altogether brave. He had another talent, that of stealing Gestapo vehicles from local motor pools. His citation for the British award making him a Member of the Most Honourable Order of the British Empire reads in part:

“For four months this officer assisted in the organization of the maquis in a most difficult department where members were in constant danger of attack…he ran great risks in looking after four RAF officers who had been brought down in the neighborhood, and accompanied them to the Spanish border [at the Pyrenees]. In the course of his efforts to obtain the release of these officers, he raided a German military garage and took ten Gestapo motors which he used frequently … he procured a Gestapo pass for his own use in spite of the fact that he was well known to the enemy….

“The UNION team experienced great problems in getting the area organized. Money was short and there was a lack of transportation. Security at the regional and departmental levels was poor, and there was the country-wide problem of getting resistance organizations with divergent political views to cooperate. The maquisards lacked heavy weapons, basic gear such as blankets, field equipment, radios, ammunition, and the list goes on. In the midst of all this, in late May 1944, before D-Day at Normandy, the UNION team with withdrawn to England for further

assignments.

In England, he was decorated with the first of two Navy Crosses he was to earn. The citation for the first read:

“For extraordinary heroism while attached to the United States Naval Command, Office of Strategic Services, London, England, in connection with military operations against an armed enemy, in enemy-occupied territory, from 8 January to 20 May 1944. Operating in civilian clothes and aware that he would be subject to execution in the event of his capture, Major Ortiz parachuted from an airplane with two other officers of an Inter-Allied mission to reorganize existing Maquis groups and organize additional groups in the region of Rhone. By his tact, resourcefulness and leadership, he was largely instrumental in effecting the acceptance of the mission by the local resistance leaders, and also in organizing parachute operations for the delivery of arms, ammunition and equipment for use by the Maquis in his region. Although his identity had become known to the Gestapo with the resultant increase in personal hazard, he voluntarily conducted to the Spanish border four Royal Air Force officers who had been shot down in his region, and later returned to resume his duties. Repeatedly leading successful raids during the period of this assignment, Major Ortiz inflicted heavy casualties on enemy forces greatly superior in number, with small losses to his own forces. By his heroic leadership and astuteness in planning and executing these hazardous forays, Major Ortiz served as an inspiration to his subordinates and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

Ortiz, who had been promoted to the rank of Major, returned to France on 1 August, the head of a mission entitled UNION II. This was a new type of OSS mission, an Operational Group. These were heavily armed contingents which were tasked with direct action against the Germans. They were not only to conduct sabotage, but also were to seize key installations to prevent retreating German units from destroying them. Team members were always in uniform. Accompanying Ortiz on this mission were Air Corps Captain Francis Coolidge, Gunnery Sergeant Robert La Salle, Sergeants Charles Perry, John P. Bodnar, Frederick J. Brunner, and Jack R. Risler, all Marines, and a Free French officer, Joseph Arcelin, who carried false papers identifying him as a Marine.

This was a daylight drop near the town of les Saises in the Haute Savoie region. In addition to the team, a large supply of weapons and ammunition and other supplies in 864 containers for the French Bulle Battalion operating in the region were also dropped. The mission began badly, for Perry’s steel parachute cable snapped, and he was dead in the drop zone. His comrades buried him with military honors.

During the week after they arrived in France, UNION II instructed the members of the Bulle Battalion on the functioning and maintenance of the new weapons they had just received. Then they began a series of patrols in order to link up with other resistance groups believed to be operating in the area. In an activity report, Brunner later stated:

“On 14 August we proceeded to Beaufort where we made contact with other F.F.I. [Forces Francaises de l’iInterieur] companies and from there went on to Montgirod where we were told there were heavy concentrations of Germans. We were able to enter the town but had no sooner done so than we were heavily shelled by German batteries located in the hills around the city. We were forced to retire and hid out in the mountains near Montgirod with the Bulle Battalion. The Germans quickly surrounded the area.”

Two days later, Ortiz and his group were surprised in the town of Centron by elements of the 157th Alpine Reserve Division, consisting of 10-12 heavy trucks in which there were several hundred troops. The convoy was headed for the garrison of Bourg-St. Maurice, northeast of Centron. [Ironically, by 20 August, the Germans were in confused retreat after the Allied landing in Southern France on 15 August. Also ironically, the first American jeep entered Albertville, in the Haute Savoie, on 22 August.] The surprise was mutual. Spotting the Americans, the trucks screeched to a halt and soldiers tumbled out and began firing. Brunner later recalled:

“Major Ortiz, Sergeant Bodnar and Sergeant Risler withdrew into the southwest section of the town. Captain Coolidge, ‘Jo-Jo’ [the French member of the team] and I took the southeast. We retaliated as best we could, working our way under fire toward the east. I called out to ‘Jo-Jo’ to follow us but he remained in the town. At this time, Captain Coolidge received a bullet in the right leg but he kept going. By then we had reached the bank of the Isere. I dived in and swam across under fire. I had some difficulty as the current was very swift. It was then that I became separated from Coolidge and did not see him again until we met … on 18 August [at the location of another resistance group].”

Ortiz, Risler, and Bodnar were receiving the bulk of the German fire. As they retreated from house to house in Centron, French civilians implored them to give up in order to avoid reprisals. Ortiz ordered the two sergeants to get out while they could, but neither would go without him. Ortiz recognized that if he and his men shot their way out of the entrapment, local villagers would undoubtedly suffer for Germans deaths which a firefight surely would have produced. He knew of the massacre at Vassieux and the destruction of the town of Oradur-sur-Glane and all of its inhabitants. In his after-action report given after his liberation from a POW camp, Ortiz stated:

“Since the activities of Mission Union and its previous work were well know to the Gestapo, there was no reason to hope that we would be treated as ordinary prisoners of war. For me personally the decision to surrender was not too difficult. I had been involved in dangerous activities for many years and was mentally prepared for my number to turn up. Sergeant Bodnar was next to me and I explained the situation to him and what I intended to do. He looked me in the eye and replied, ‘Major, we are Marines, what you think is right goes for me too.’”

Ortiz began shouting to the Germans in an attempt to surrender. When a brief lull ensued, he stepped forward and calmly walked toward the Germans as machine gun bullets kicked up dust around him. Finally the firing stopped, and Ortiz was able to speak to the German officer in command. The major agreed to accept the surrender of the Americans and not harm the townspeople. When only two more Marines appeared, the major became suspicious and demanded to know where the rest of his enemy were. After a search of the town, the Germans accepted the fact that only three men had held off a battalion.

Bodnar and Risler were quickly disarmed and Ortiz called them to attention, and directed that they give only their names, ranks, and serial numbers as required by the Geneva Convention’s terms relating to the treatment of prisoners of war. This greatly impressed the Germans, who began treating them all with marked respect.

From that time, until 29 September, when he reached his final destination, the naval POW camp Marlag/Milag Nord located in the small German village of Westertimke outside Bremen, Ortiz looked for every opportunity to escape, but none presented itself. Fortunately for Ortiz and the other prisoners, this prison camp was loosely controlled in that outside of periodic searches and roll calls three times a day, the POWs were left to themselves. Still, Ortiz tried to escape several times, despite the fact that the senior Allied POW was a Royal Navy captain who made it plain to the new arrival that escapes were out. Ortiz then declared himself the senior American POW present and that he would make his own rules.

Allied forces were drawing closer each day, and suddenly, on 10 April, the camp commandant ordered all POWs to prepare to leave within three hours. The column left with such haste, that a number of the prisoners were left behind. Not Ortiz, for special watch was kept over him. En route, the column was attacked by diving Spitfires, whereupon Ortiz, and three other prisoners made for a nearby wood, and waited for the column to continue on, which it did, leaving him and his fellows behind unnoticed. Allied progress was slow, and the escapees were not rescued as quickly as they thought they would be. Ortiz later reported:

“We spent ten days hiding, roving at night, blundering into enemy positions hoping to find our way into British lines. Luck was with us. Once we were discovered but managed to get away, and several other times we narrowly escaped detection…By the seventh night, we had returned near our camp. I made a reconnaissance of Marlag O …. There seemed to be only a token guard and prisoners of war appeared to have assumed virtual control of the compounds.”

The escapees were in bad physical shape. On the tenth day, the four men decided it might be better to live in their old huts than to starve to death outside. They walked back into the camp, no commotion was raised by the guards, and the remaining POWs gave them a rousing welcome. Among the reception committee were Bodnar, Risler, and the French “Marine,” Jo-Jo–Joseph Arcelin. The battle reached Westertimke on 27 April, and two days later, the British 7th Guards Armoured Division liberated the camp. Along with Bodnar, Risler, and Second Lieutenant Walter Taylor, another OSS officer who had been captured in Southern France, Ortiz reported to a U.S. Navy radar officer assigned to a Royal Marine commando attached to the Guards Division. The Marines wanted to join this unit in order to bag a few more Germans before the war was ended. Their request was refused.

Ortiz and his fellow Marines were sent to staging areas behind the front, and then to Brussels where he reported to the OSS officer-in-charge. He then was sent to London, where he was awarded his second Navy Cross, the citation for which read:

“For extraordinary heroism while serving with the Office of Strategic Services during operations behind enemy Axis lines in the Savoie Department of France, from 1 August 1944, to 27 April 1945. After parachuting into a region where his activities had made him an object of intensive search by the Gestapo, Major Ortiz valiantly continued his work in coordinating and leading resistance groups in that section. When he and his team were attacked and surrounded during a special mission designed to immobilize enemy reinforcements stationed in that area, he disregarded the possibility of escape and, in an effort to spare villagers severe reprisals by the Gestapo, surrendered to this sadistic Geheim Staats Polizei [sic]. Subsequently imprisoned and subjected to numerous interrogations, he divulged nothing, and the story of this intrepid Marine Major and his team has become a brilliant legend in that section of France where acts of bravery were considered commonplace. By his outstanding loyalty and self-sacrificing devotion to duty, Major Ortiz contributed materially to the success of operations against a relentless enemy, and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

Ortiz returned to California and civilian life in the movie industry as both a technical advisor and as an actor. He was a good friend of director John Ford, who put him in a couple of John Wayne movies. He wasn’t the greatest of actors, and he never really liked seeing the movies he was in. He remained in the Marine Corps Reserve, reaching the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. He was offered the command of a reserve tank battalion located in San Diego, but had to turn it down because his commitments in Hollywood kept him quite busy. In April 1954, he wrote a letter to the Commandant, volunteering to return to active duty to serve as a Marine observer in Indochina. The Marine Corps was unable to accept Ortiz’ offer because “current military policies will not permit the assignment requested.”

He retired in March 1955 and was promoted to Colonel on the retired list for having been decorated in combat. In October 1945, the French government decreed him a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour. He also received the Croix de Guerre with five citations, the Medaille de Blesses, Medaille d’Evades, Medaille Coloniale. In addition to his two Navy Crosses, his American awards included the Legion of Merit with Combat “V” and two Purple Heart Medals. And, as noted earlier, he was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire (Military Division). On 16 May 1988, Colonel Peter J. Ortiz, USMCR (Ret) died of cancer, and in doing so, lost the only battle of the many he fought. He was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery, with military representatives of the British and French governments present.

While the name of Peter Ortiz may not be well known to present-day Marines or to the American people, it is certain that the citizens of les Saisies or of Centron will never forget him and the Marines who fought with him in France. Both towns commemorated the anniversaries of the major events which occurred in each place 50 years earlier. Invited to attend the ceremonies in August 1994 were Colonel Ortiz’ wife, Jean, and their son, Marine Lieutenant Colonel Peter J. Ortiz, Jr., retired Sergeant Major John P. Bodnar, and former Sergeant Jack R. Risler. Also present at the ceremonies were Lieutenant Colonel Robert L. Parnell II, USMC, assistant Naval Attaché in Paris, and Colonel Peter T. Metzger, commander of the 26th Marine Expeditionary Unit, then in the Mediterranean, together with a color guard and an honor guard from his unit.

On 1 August 1994, the ceremonies at les Saisies began in the afternoon with a parachute drop made by French troops. Members of the famous Chasseurs Alpins together with the 26th MEU Marines rendered honors as a monument acclaiming the 1994 event was dedicated. Twelve days later, the town of Centron held its own

ceremonies when it unveiled a plaque naming the town center “Place Peter Ortiz.” This event was attended by many former members of the local maquis unit in the region, as well as the Marine contingent and Mrs. Ortiz and her son. As an aside, during CBS’ coverage of the last Winter Olympics in Albertville and the surrounding region, Charles Kuralt had a 20-minute spot about Peter Ortiz, telling of his exploits.

Peter Julien Ortiz was a man among men. It is doubtful that his kind has been seen since his time.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard