Richard Michael Mancini was born on February 17, 1937 and joined the Armed Forces while in Amstedam, New York.

He served as a AE2 in the Navy. In 10 years of service, he attained the rank of AE2/E5.

Richard Michael Mancini is listed as Missing in Action.

Wednesday, May 07, 2003

Courtesy of the Gloversville, New York, Leader Herald

Homeward Bound: Mayfield man retrieving remains of father killed in Vietnam War

MAYFIELD, New York – Navy 2nd Class Petty Officer Richard Michael Mancini is coming home.

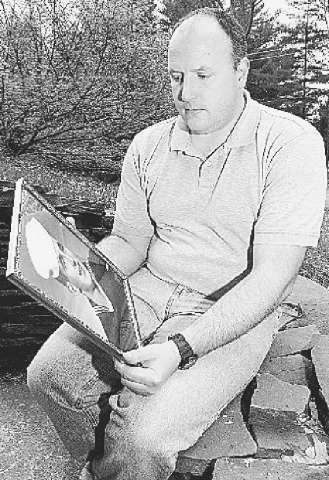

His son – Richard J. Mancini of Progress Road – is traveling to Hawaii Monday to bring back the remains of a father he never knew in life, but certainly in spirit. The elder Mancini, an aviation electrician, was killed 35 years ago when the plane he, eight others and a dog, Snoopy, were in crashed into a mountain in Laos during the Vietnam War.

The remains of all were found in 1996, and for the younger Mancini, now 36, the logistical adventure of recovery and having his dad properly laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia is nearly over.

“It ended up most of my life that I didn’t miss something I really had,” Mancini says now.

He said he realizes that everybody in the extended Mancini family – including his 66-year-old mother, Rosemarie, who lives in a Fultonville nursing home – lost something when his father died.

Mancini and his wife, Nancy, have an 18-month-old son, Niko, who is about the same age he was when his father met his untimely fate.

“I was too young to remember, but now I feel having my own son, I have somewhat of a connection,” says Mancini.

It was not a case of enemy fire on January 11, 1968, when Richard M. Mancini, his fellow crew members and their trusted canine perished in their Neptune OP-2E. Their unit was out of the Navy’s VO-67 Squadron, which was dropping modified accouebouys to detect the Viet Cong in Laos.

The OP-2E was flying an American Top Secret acoustic and seismic reconnaissance mission along the Ho Chi Minh Trail to sniff out troop and munitions movements by the North Vietnamese. When they would find something, they would call in air strikes. But on the day of the mission January 11, things went terribly wrong.

“They were flying and dropping sensors into the treetops,” Mancini said.

His father, at the time a 30-year-old airman from Amsterdam, was flying along with these other volunteer squadron members: pilot and Commander Delbert A. Olson, Lieutenant (jg) Denis L. Anderson, Lieutenant (jg) Arthur C. Buck, Lieutenant (jg) Philip P. Stevens, AO2 Michael L. Roberts, ADJ2 Donald N. Thoresen, PH2 Kenneth H. Widon and ATN3 Gale R. Siow. All their remains, including Snoopy’s, were later found.

The plane was over the Boualapha District, Khammouan Province. It was a type of aircraft that had served in the Vietnam War from 1967-68. Eventually, the squadron would be disbanded, and men rotated back to the states.

But as Mancini tells the story, on January 11, his father’s OP-2E ran into some difficult environmental conditions.

President Lyndon Johnson was counting on the mission to detect the movement of North Vietnamese forces into South Vietnam.

The first pass by Mancini’s plane was too high, but sensors were dropped.

In the mountainous area, the pilot tried to pull up, but heavy cloud cover contributed to the plane’s crash.

Government documents obtained by the younger Mancini said the plane wound up “burning and sliding” into a mountain.

The plane wreckage was spread over four ledges and the crew’s remains had to withstand 35 years of monsoons and overgrowth.

Mancini said he learned later his mother, Rosemarie, was devastated by her husband’s death. But he said the mission ended up saving many lives during that period of the protracted Vietnam conflict. The Navy man’s status went from missing in action to killed in action within 90 days.

Later, the crash would be deemed an accident.

Mancini grew up in Gloversville, New York, and he said he tried to learn what happened to his father, basically only knowing that he died in a plane crash during the war. The federal government has a Joint Task Force Full Accounting arm of the U.S. Department of Defense.

After the remains were found in 1996, the site was closed for awhile, but the 35- to 90-member JTFFA crews went back four times. Mancini said the task force never came up with conclusive proof that his dad’s crew was killed by anti-aircraft fire.

“They were a crew of dedicated men attempting to carry out a mission,” Mancini said.

Commander Donald McKnight of the Navy Marine Reserve office in Albany has been serving as a liaison to the rest of the military for Mancini and his family.

As a casualty assistance call officer, he said he is glad to assist.

“This is a big deal for the Navy,” McKnight said. “I told Rich this is certainly an honor for me to help take care of a shipmate, even though it was from the 1960s.”

Mancini’s father was a 1955 graduate of Amsterdam High School and later went into the Navy. The younger Mancini said his mother gave birth to him in Washington state. After the crash, Mancini said his mother was notified but was having trouble accepting it.

“My mom didn’t want to believe my father was killed,” Mancini said.

Mrs. Mancini would watch TV accounts of troops coming home from Vietnam, hoping her husband would step off a plane.

Meanwhile, Rich Mancini said, life went on as a kid in Gloversville.

“I didn’t miss out on the things that normal children do,” he said. Mancini said he played football and baseball. Instead of his dad being there, his grandfather, the late John Sweeney, often was.

Seven years ago, when Mancini was contacted by the federal government that there was an opportunity to excavate his dad’s crash site, the government said it needed DNA samples. Blood samples were taken from the deceased Navy man’s mother, Ann, and his brother, Michael, who were living in Amsterdam at the time.

“We hurried up and waited,” Mancini said.

Permission for much of the work by the JTFFA had to be secured from three local governments – Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. The excavation crews were only allowed to work on certain days. Needless to say, it was not an immediate identification of the deceased sailors.

As of 2001, the JTFFA has been involved in 3,405 cases and 590 excavations in Southeast Asia. About 2,000 Vietnam War troops remained unaccounted for as of 2001.

Finally, positive identification of Richard Mancini’s remains, including a femur, was made. On March 7, 2003, the government presented Mancini and his mother with a 400-page case file on the Navy man’s death.

Ironically, the family later found out that one of the JTFFA men involved in the dogged fight to recover the remains – David Runkin or Arizona – is related to Nancy Mancini.

Richard Mancini said he continued to press for information and wrote e-mails to get more data. Asked if the military handled the situation well in Vietnam, he doesn’t hesitate.

“I believe they did the best they could with what they worked with,” he said. Since the administration of former President Ronald Reagan, and the ending of the Cold War in the 1980s, he feels America has committed itself to bringing men home from Vietnam. But he said the search is tough, and often too tough and dangerous for recovery crews to go back in.

For example, Mancini said 13 men, including seven Americans, were killed in a recovery mission in Vietnam in April 2001.

Mancini said he has met co-pilot Anderson’s wife and pilot Olson’s son.

Every year, he said the JTFFA holds briefings and conferences in Washington, D.C., which he has attended.

He hopes to attend the services of three other men killed in his father’s plane. But now, it’s time to bring his father home. His wife, Nancy, will be staying in Gloversville with their son while her husband goes to Hawaii for his dad.

“It’s quite overwhelming to a lot of the senses,” Nancy Mancini said.

Because of the connection between her husband and their son, and how young her husband was when his father died, she said, “It kind of strikes home with me.”

But Nancy Mancini says there is some closure to this life experience on the horizon.

Richard Mancini will be taking time off from his job as associate director of Bethesda House in Schenectady. He will be spending about four to five days at Hickam Air Force Base’s Central Identification Lab in Hawaii before returning May 16, 2003.

“I will be allowed to view his remains,” he said. “I really don’t have any preconceived thoughts and emotions.”

The remains will be flown from Hawaii to Albany accompanied by an honor guard, Mancini said.

A viewing will take place at an Amsterdam funeral home May 18, 2003, with a service the next day.

The Navy airman’s interment will be May 20, 2003, in Arlington National Cemetery, the choice of the family, with several Mancini family members present.

“That was my mother’s decision,” Mancini said. “She, in essence, felt it was an honor for him being buried there.”

Even though his mother is ill, she will be attending. A decision has already been made to have Rosemarie, who never remarried, buried along side her husband.

“She’s nervous about flying,” Mancini said. “She’s excited about finally being a step closer to closure.”

During his life, Mancini thought about joining the military, but said he didn’t want to put his mother through that. He wonders if that was ever meant to be.

He characterizes the journey to find out more about his dad – and then actually finding his father – as “incredibly interesting to me.” He said he would normally be fascinated with such a story if it was on the Discovery Channel, but “to live through it is an entirely different dimension.”

All along, he said he felt something was missing in his life.

His father, Mancini said, is “certainly” a war hero.

He said he has gained new insight into the experiences of service personnel through recent coverage of the war in Iraq.

“My belief in our military personnel is that they have enriched a sense of duty and commitment, honor and courage,” Mancini said.

After 35 years, son will bring back remains of father

10 May 2003

MAYFIELD, New York – Navy Petty Officer 2nd Class Richard M. Mancini is coming home.

His son, Richard J., will travel to Hawaii on Monday to bring back the remains of the father he never knew in life, but did in spirit. The elder Mancini, an aviation electrician, was killed 35 years ago when the plane carrying him, eight others and a dog crashed into a mountain in Laos during the Vietnam War.

The remains of all the fliers were found in 1996, and for the younger Mancini, now 36, the logistical adventure of recovery and having his father properly laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia is nearly over.

“I was too young to remember, but now I feel, having my own son, I have somewhat of a connection,” Mancini said.

The Neptune OP-2E crashed Jan. 11, 1968, while flying an acoustic and seismic reconnaissance mission along the Ho Chi Minh Trail to sniff out troop and munitions movements by the North Vietnamese. An honor guard will accompany the remains on the flight from Hawaii to Albany, Mancini said. A funeral will be held May 19 in Amsterdam, and burial in Arlington National Cemetery is planned for May 20.

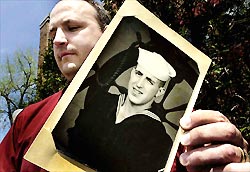

More than three decades after Richard M. Mancini died in the Vietnam War, his body is coming home.

Petty Officer 2nd Class Mancini, 30, of Amsterdam, a career Navy man, was part of a crew of nine men on a top-secret mission when their plane crashed in Laos on January 11, 1968.

Originally listed as missing in action, his status was classified to killed in action. The plane and the crew’s remains were discovered in 1996 on the peak of Phou Louang. Identifying the men took seven years.

Until he had a son of his own, Mancini’s son, Richard “Rick” Mancini, said he didn’t miss having a father.

Rick Mancini was 18 months old when his father died. Now his son, Niko, is the same age.

“Growing up, I didn’t feel I had missed out. I just didn’t have a father,” said Rick, 36. “I was in a situation that I had no real memories of my father. I’m saddened and disappointed that I can’t remember those times. I know the fun and enjoyment I have with my boy.”

On Monday, Rick Mancini flies to Hawaii to escort his father’s remains home, the first leg of a journey that will end May 20 with a military funeral at Arlington National Cemetery.

“I’m feeling honored. I’m feeling, I guess, a bit overwhelmed with all the arrangements that need to make this happen,” Mancini said. “There’s a whole variety of different feelings. It’s hard to put into words.”

His mother, Rosemarie, never remarried after her husband of five years died. She is now ill and lives in a nursing home near Gloversville.

“My mom is feeling sad yet relieved,” Rick said. “Whatever closure encompasses, she’s going through that process. She wishes to have my father interred in Arlington.”

One person who worked closely with Mancini said the son was an active source in securing the crew’s return.

“Rich has been involved with this thing for a number of years. He’s been very proactive seeking out information on his own,” said Commander Donald McKnight, who is stationed at the Navy Marine Reserve Office in Albany.

“He’s been working with other family members of the crew and people that were in the squadron,” McKnight said.

“This is really the Mancini story,” McKnight said. “I was telling some fourth-grade kids today, we’re all part of the big Navy family. It’s my duty, my honor and my privilege to help.”

Rick Mancini uncovered another family tie in his efforts to find his father.

David Rankin, the forensic anthropologist who identified the remains, is a cousin of Mancini’s wife, Nancy. They won’t be able to meet when Rick Mancini arrives at the base in Hawaii. Rankin will be in Vietnam working on another case.

“Not only is he family, but he is directly responsible for identifying all of them,” Mancini said.

The other crew members were Commander Delbert A. Olson, Lieutenant (jg) Denis L. Anderson, Lieutenant (jg) Arthur C. Buck, Lieutenant (jg) Philip P. Stevens, and Michael L. Roberts, Donald N. Thoresen, Kenneth H. Widon and Gale R. Siow. Their mascot, a dog named Snoopy, was also on board when the plane went down.

Mancini will return to Albany with his father’s remains on Friday. Family and friends will gather from 2 to 4 p.m. Sunday, May 18, 2003, at the Betz, Rossi & Bellinger Family Funeral Home Inc., 171 Guy Park Ave., Amsterdam, New York. The funeral is at 9:15 a.m. Monday, May 19, at St. Michael’s Church in Amsterdam.

Burial is to be Tuesday, May 20, at Arlington National Cemetery. When she dies, Mancini said, his mother will be buried there with his father.

On June 18, 2003, the unidentified remains of the plane’s crew, including those of Snoopy, will be buried. Mancini also will attend that service.

As for the future, Mancini said, “It would be important for me to make periodic trips to visit my parents, my father first and my mother, as a sign of respect.”

Click here for additional information

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard