Army, dignitaries and Seattle friends

say goodbye to Stanford

Courtesy of the Seattle Times

Thirteen shots from a howitzer echoed across the Virginia hills today as the nation’s top military and educational leaders gathered to bury John Stanford.

The popular Seattle schools superintendent, a retired Army two-star general, died Saturday morning at age 60 after an eight-month battle with leukemia.

Stanford’s widow, Patricia, walked slowly behind his horse-drawn casket on the way to the grave. Ahead was a riderless horse with a single boot turned backward in the stirrup, an Army tradition signifying that the warrior would go to battle no more.

Many in the crowd of 200 sobbed quietly as an Army bugler played taps.

Symbolizing Stanford’s success in both the military and in education, his funeral was attended by high-ranking mourners from both arenas. Among them were General Colin Powell, the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Education Secretary Richard Riley. Five four-star generals attended the service.

Vice President Al Gore planned to meet with Stanford’s family in the White House this evening after returning from a trip.

In a eulogy, the Rev. Elbert Ransom Jr., a friend of the family who had been their pastor when they lived in Virginia, remembered Stanford as an electric personality who will make his mark in the afterlife.

“Pat Stanford said the other day that she would assume John is in heaven, and God had better watch out because he will reorganize it,” Ransom said.

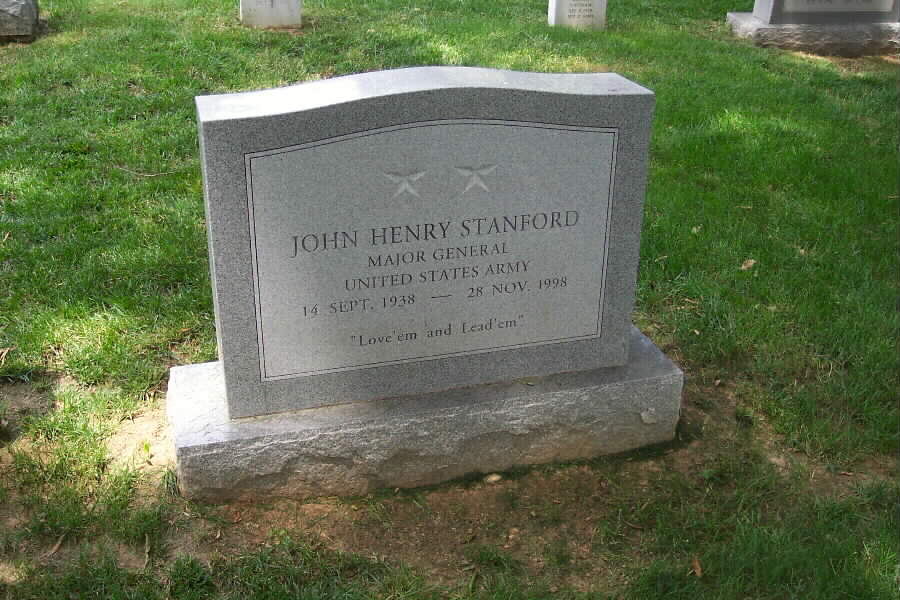

Stanford was buried with full military honors in the nation’s famed military cemetery. He spent 30 years in the U.S. Army, serving in Korea, Vietnam and the Persian Gulf, rising to the rank of major general.

After his flag-draped casket traveled a half-mile through the cemetery on a horse-drawn caisson, Stanford was buried in a grove of oak trees near the grave of heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis, who was an Army sergeant in World War II.

People who knew Stanford said he would have loved his spot four rows from the great African American boxer.

“You can’t ask for a more appropriate sleeping mate than Joe Louis,” said Joseph Olchefske, acting superintendent of Seattle schools. “Grit, heart and persistence – that’s Joe Louis, and that’s John Stanford.”

Some onlookers who didn’t know Stanford personally were drawn to the funeral anyway, even though there was no room inside the chapel. Joann Bagnerise, a grandmother from Dumfries, Va., 30 miles to the south, had only read about Stanford in the newspaper. But she brought her 3 1/2-year-old grandson, Joseph, because she wants him to “be just like Stanford when he grows up.”

“Joseph was supposed to be in preschool today, but I thought he should come and learn about a great, great man,” Bagnerise said.

Stanford was honored in a service in the cemetery’s tiny Memorial Chapel, which seats only 150. It was packed with dignitaries, including the top-ranking officer in the Army, Chief of Staff Dennis Reimer.

Also attending was a delegation from the Seattle schools.

“This morning we deliver to God the body and soul of John Henry Stanford,” Don Nielsen, vice president of the Seattle School Board, told the mourners. “We do not, however, relinquish his spirit.”

The customer-service manager of Seattle schools, Sue Byers, sang two solos in memory of Stanford, “How Great Thou Art” and “If I Can Help Somebody.”

A boyhood friend, Fred Terrell, said he had known Stanford for 53 years and that he had never really changed. He said that when they were young in Pennsylvania, they organized a group of neighborhood kids.

“For all his accomplishments,” Terrell said, “he always remained part of the Backyard Gang.”

The funeral procession included a 24-piece Army band and a full company of “The Old Guard,” the 3rd U.S. Infantry.

After the burial, attendants folded the flag that had been on the casket, and Reimer presented it to Stanford’s widow.

Ransom concluded his eulogy by recalling one of Stanford’s favorite responses, whenever someone asked him how he was doing.

“I am perfect, and improving,” Stanford would say. “But of course you knew that.”

Full-honors military funeral is steeped in tradition

Courtesy of the Seattle Times

When John Stanford is buried tomorrow, the funeral procession through Arlington National Cemetery will include a single, riderless horse, wearing an empty saddle.

In one stirrup will be a cavalry boot, turned backward – an indication the retired Army major general will never ride again.

From beginning to end, a funeral with full military honors is a strict ceremony packed with hundreds of years of tradition.

“It’s a beautiful, poignant event that the military does very well, but a lot of the symbolism can be lost on the public,” said Dov Schwartz, an Army spokesman.

Here is what will happen during the burial service, scheduled for 7 a.m. Pacific time (local TV stations plan to include footage in their newscasts):

— After a brief service in Arlington’s Memorial Chapel, Stanford’s casket will be loaded onto a caisson, a horse-drawn carriage built in 1918 that was once used to carry 75 mm cannons and ammunition chests.

— A procession will leave the chapel for Section 7A of America’s most famous burial ground, about a half-mile away, where Stanford will be interred. Among those buried in this section are General Roscoe Robinson Jr., the first African American in the Army to attain the rank of four-star general; Commander Michael Smith, pilot of the Space Shuttle Challenger that exploded in 1986; and Clark Clifford, an adviser to four presidents who was Secretary of Defense during the Vietnam War.

— A 24-piece Army Band will lead the procession, playing music selected by Stanford’s family: “How Great Thou Art,” “Rock of Ages” and “Amazing Grace.”

— Behind the band will march troops from the 3rd U.S. Infantry, also known as “The Old Guard,” the oldest active-serving infantry unit in the nation. Established in 1784, this unit guards the nearby Tomb of the Unknowns 24 hours a day.

— The casket will be drawn by six white horses. All will have saddles, but only three will have riders – echoing the fact that when the caisson was used to carry artillery, half the horses would carrysupplies.

— Behind the casket, after the riderless horse, come honorary pallbearers, and then Stanford’s family.

— When the procession reaches the grave, Stanford’s casket will be carried to the side of the grave and the flag stretched taut and centered over the casket. A chaplain will perform a brief service, followed by a cannon salute. Begun by the British Navy, the salute is meant to symbolize respect and trust, because firing the cannons would disarm the ship, leaving it vulnerable to attack. Two-star generals are entitled to 13 shots.

— The chaplain will complete a benediction, then a seven-person rifle team will fire a three-round volley over the grave, for a total of 21 shots. (This is different from a 21-gun salute, which is performed with cannons, and only for a president.) The tradition descends from an old custom: troops would halt fighting to remove the dead

from the battlefield, then fire three volleys into the air to signal it was time to resume fighting.

— A bugler will play “Taps.” The song, so named because it once was tapped out using a drum, became part of military funerals during the Civil War when it was substituted for the louder rifle volleys in some funerals so as not to arouse the enemy camped nearby.

— Assembled troops will fold the flag and give it to the chaplain, who will present it to Stanford’s widow or family.

John Stanford, Seattle’s voice for children,

dies after battle with leukemia

Courtesy of the Seattle Times, Sunday, 29, November 1998

When Don Nielsen made one of his last visits a week ago, John Stanford needed an oxygen mask to breathe. But he had lost none of his passion.

Though ravaged by cancer and repeated chemotherapy, Mr. Stanford had a message for his friend: “I want you to know I am not quitting,” he said. “I don’t want you to quit, and I don’t want my family to quit, and I don’t want the kids to quit.

We’ve got so much to do, we can’t stop.”

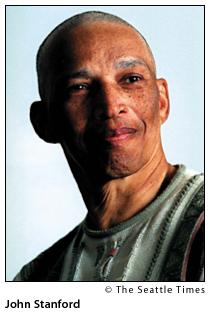

Yesterday, John Henry Stanford finally succumbed to acute myelogenous leukemia after an eight-month battle. The Seattle schools superintendent died at 1:35 a.m. at Swedish Medical Center. He was 60.

With his death, Seattle has lost not just the charismatic leader of its schools but a nationally respected advocate for education, a voice for children, an activist who inspired fellow African Americans, a leader whose energy and vision captured the hopes and hearts of a city.

Those memories were shared yesterday at a quiet, informal memorial for Mr. Stanford near the International Fountain at Seattle Center that drew about 250 people. Their stories illustrated the breadth of roles Mr. Stanford filled for many people – stories of a man whose style, leadership and personal integrity touched people on so many different levels.

His wife, two sons and two sisters were with him at the end. His younger son, Scott, said his father seemed to be at peace, and “seemed to be aware of what was happening.”

The family released a statement last night expressing its gratitude to the citizens of Seattle. “His love affair with you was boundless and sincere, and the way you reflected that passion on him never ceased to amaze him,” the statement said.

Mr. Stanford had been in the hospital since Oct. 16, the day after he announced his leukemia had returned for the third time. But he remained fiercely determined to beat the cancer until the end.

Only a week ago, he summoned district spokesman Trevor Neilson to his hospital room and spent several hours talking over school business, including planning for a January event for school supporters. It was with amazement and some sorrow that Neilson realized Mr. Stanford expected to attend the event.

In Seattle, “John found the job he was born to do,” said Don Nielsen, vice president of the School Board, who helped recruit Mr. Stanford for the job more than three years ago and then became a close friend.

Success before arriving here

Mr. Stanford was born Sept. 14, 1938, in the Philadelphia suburb of Darby, Pennsylvania. After a successful career in the U.S. Army, from which he retired as a major general in 1991, he served as manager of Fulton County, Georgia., before coming to Seattle as school superintendent in 1995.

At the time, Mr. Stanford was one of the few noneducators hired to lead a large school district. He was Seattle’s first African-American superintendent.

With his commanding leadership style and infectious optimism, he brought a sense of hope and excitement about public schools to Seattle.

Test scores, enrollment, public support and private donations to the schools all increased during his tenure.

National reporters were constantly writing about him, and he was sometimes compared by the media to his longtime friend, retired General Colin Powell.

Political leaders marveled at his charisma and popularity. Paul Berendt, chairman of the Washington Democratic Party, never approached Mr. Stanford about running for office, but said he had all the characteristics of a political leader.

“Had he lived, he certainly would have been a figure that people would have considered as a possible candidate for the U.S. Senate or Congress,” Berendt said.

Yesterday, as flags at district headquarters flew at half-mast, reaction to the news of his death poured in from across the state and nation, from Governor Gary Locke to schoolchildren to far-flung friends who watched Mr. Stanford’s remarkable career.

At the Seattle Center memorial service, many remembered a man who gave the Seattle School District something it had sorely lacked for years – self-confidence.

An easel holding an oversized district portrait of Mr. Stanford was surrounded by a U.S. flag, flowers, candles and green folding chairs arranged in intimate semi-circles where people clustered to share stories and memories.

“There had been so much cynicism in the district for so many years. When he came in, he just – he refused to be cynical. It was so refreshing,” said Nancy Hunn, a first-grade teacher at Latona Elementary. “He came in and niggled people, poked them in the ribs, made them think about the way things were done.

“Now, everybody is saying, `We’ll keep it all going in his memory, and we’ll never forget,’ ” Hunn said.

“I just hope it’s true.” Matt Weintraub, a seventh-grader at Washington Middle School, said he and his friends admired Mr. Stanford and thought of him as a sincere advocate for them.

When he visited schools, “What he said wasn’t like a rehearsed speech he was giving at every school,” Weintraub said. “He was really a great man. He was really changing things.”

Roger Erskine, executive director of the Seattle Education Association, said he tried to visit Mr. Stanford on Friday in the hospital but was told he was too ill. He wanted to tell him: “If the worst happens, I’m not going to let your vision die.”

“I’ve lost a really good friend . . . the best partnership I ever had in 35 years,” Erskine said.

The two often discussed education and leadership philosophy, and Erskine remembers the day Mr. Stanford called to say he’d created a new phrase to capture a theme of their discussions, a phrase that became his mantra: “The victory is in the classroom.”

“He said, `OK, I’m a believer now,’ ” Erskine said. “It was probably my best day ever.”

Steve Sherman brought three of his young children to the Seattle Center gathering and walked each of them up to Mr. Stanford’s photograph, whispering in their ears that they should not forget him.

“I thought it was a proper way to give our gratitude to him for everything he did,” Sherman said. “I think he’s changed things for my kids’ lives, and I wanted them to come down and appreciate him.”

Like many white middle-class residents in Seattle, Sherman said, he weighed whether to place his children in public or private schools. It was Mr. Stanford, he said, who persuaded him to make an investment in public education.

African-Americans say they will remember Mr. Stanford for the voice and respect he brought to minority children.

Jacqualine Brown, a counselor at Thurgood Marshall Elementary School, and Lavern Loud, a teacher at Wing Luke Elementary School, relished the way Mr. Stanford waved away the traditional explanations about why many minority children haven’t done well academically, how he dispensed with the concept that “at-risk kids” were destined to come up short of success.

“With (Mr. Stanford) coming in, it challenged all the people to get rid of the excuses,” Brown said.

Loud said she saw many colleagues straighten up and try harder when Mr. Stanford began talking about accountability and responsibility for student success.

For the first time in years, both said, many minority parents also have been coming to school asking, “What can I do? How can I help?”

Mr. Stanford’s call for family nurturing and responsibility was particularly powerful, the two said, because it came from a man who had become one of the most prominent African Americans in the country.

“Parents of color may have felt, `My child may not be as successful,’ and he changed that perception,” Brown said. “Here was a man of their color who cared about their kids.”

He leaves a legacy

District, city and state leaders spoke of Mr. Stanford’s legacy and asked mourners to dedicate themselves to carrying his vision forward.

“What a privilege it has been to work with such a remarkable man,” said Barbara Schaad-Lamphere, School Board president. “His legacy will be a focus on children . . . to have education, children’s lives, at the center of everything we do in this city.”

Seattle Mayor Paul Schell said he will remember Mr. Stanford’s spirit and his “of course we can do this” attitude. “To celebrate that spirit and carry it on to the next century is something John would be very proud of. I suppose there’s not a school superintendent in the country who’s been able to galvanize the whole country the way John Stanford did.”

Mr. Stanford was “a true education leader” who reached out across the state to speak for all schools, not just those in Seattle, said Senator Jeanne Kohl, D-Seattle. “It will be very difficult to find someone else with those capabilities.”

“I miss John already,” said acting Superintendent Joseph Olchefske. “I’ll miss him forever.”

“It’s a tremendous loss, not only to the children and the families of Seattle, but to everybody who knew him,” said Julius Johnson, a longtime military friend who worked as Mr. Stanford’s chief of staff in Seattle.

“He was such a very kind and very decent human being. . . . He wanted to make a difference, and I truly believe he did.”

One of Mr. Stanford’s favorite stories was about a fourth-grade student who jumped up during one of Mr. Stanford’s school visits and said, “Mr. Stanford, I want you to know I’m doing exactly what you said.”

“What’s that?” Mr. Stanford asked. “Reading 20 to 30 minutes every day?”

“No,” the student replied. “I’m going to graduate from the fourth grade.”

“John was so touched by that,” Johnson said. “He retold the story again and again” as evidence that if standards were raised, students would jump up to meet them.

Hero to students

Many children considered Mr. Stanford a personal hero. Olchefske recalled visiting several schools with Mr. Stanford and members of the rock band Pearl Jam. The kids ran up to Mr. Stanford, not the famous band members, Olchefske recalled.

“More than anything else, I think he is someone who cared about us a great deal as students,” said Zack Elway, student-body president at Roosevelt High School. “I don’t agree with everything he ever did, but there was never any question in my mind that he really did care.”

When students met him, “It was a big deal,” he said. “They all knew who he was and were really rooting for him throughout all of this.”

Tomorrow, the school district expects to have extra counselors in every school. “Kids in Seattle knew John, and he knew them personally. We want to make sure they have a chance to express their grief,” district spokesman Neilson said.

Malia Tuulaga, an eighth-grade student at Sharples Alternative Secondary School in South Seattle, says if not for Mr. Stanford, she wouldn’t be going to school on Saturdays to get extra tutoring in reading and computer skills. She credits him with providing the money and teachers to make more services available.

Yesterday, she and volunteer counselor Cheryl Lauifi paid their respects at Seattle Center.

“Without him, we’d have nothing,” Lauifi said. “He made it easier for the kids to go to school and not be scared. He always brought smiles to a lot of the people.”

At Madison Middle School, Principal Stephanie Haskins said teachers and others will be taking special care to reach out to students tomorrow. “He’s touched so many kids,” she said. “He’s magic with kids. He’s like a magnet.

“He was the driver that spurred us all on, and the challenge will be to stay the course without him.”

Style will be missed

Mr. Stanford’s special leadership style may be what the Seattle School District will miss most. The district is at a key point in its reform efforts, and there’s a critical need for a strong leader to carry through initiatives Mr. Stanford launched.

Making real changes in the classroom is delicate work, requiring a leader who can maintain and build on what has already been accomplished, who can win the trust of teachers using both a firm hand and a diplomatic touch.

It’s a bigger role now than it was three years ago. Mr. Stanford redefined the job of urban school superintendent to encompass civic leadership, not just school administration.

Finding someone with his unique combination of vision, energy and personal magnetism to meet the public’s new, heightened expectations is likely to prove challenging.

It’s unclear who will fill that job. The School Board has not publicly discussed what it will do next. Olchefske, the district’s chief operating officer who has been acting superintendent, will continue in that role.

Mr. Stanford is survived by his wife, Patricia; sons Steven and Scott; and sisters Cecile Stanford Williams of Yeadon, Pennsylvania, and Carolyn Stanford Adams of Miami.

A memorial service will be scheduled soon. Mr. Stanford will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, D.C.

Sunday, November 29, 1998

A letter from Stanford’s family to the citizens of Seattle

Dear Seattle:

The many people who loved John Stanford, and the depth of his reach into their lives, speak so much more about the man and the zeal with which he lived his life than any attempt here at profundity.

What remains for our family, then, is to express as best we can our deepest gratitude to the city of Seattle for all you have done for him, and for us.

His love affair with you was boundless and sincere, and the way you reflected that passion on him never ceased to amaze him. Your friendship made him more whole.

For every person that approached him on the street to say thanks, or read to your kids each night, and for every thought, word or deed in his support, please know that your kindnesses made him as happy as he has ever been.

The way you embraced what he stood for – that all children will learn – was among your finest moments, and you should be proud.

And so, as we mourn his loss together, we ask only that as you remember the dreamer, please remember his dream. There is so much left to be done: training and pay raises for teachers, the realization of vocational and international schools, more advanced-placement courses, safer campuses and better athletic programs, because he always believed sports teach us to be humble in victory and proud in defeat.

He also believed that the true measure of a leader is how the troops carry on when their leader is gone.

As for dad, and for us, we all had more in each other than anyone has the right to ask. He was great in a way that only we will truly know.

But he was greater for having been in this city. He has left you with the power to make his last, best dreams a reality, and for that we thank you, in advance.

– The John Stanford Family

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard