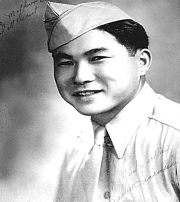

Saburo Tanamachi was a member of the famed Nisei (442nd Combat Team), made up of Japanese-Americans. Private First Class Tanamachi was killed-in-action in 1944 in the Vosages Mountains of France.

He was awarded the Silver Star Medal and the Purple Heart Medal in connection with his courageous service.

Private First Class Tanamachi was subsequently returned to the United States for burial in Arlington National Cemetery.

Courtesy of Sandra Tanamachi

Saburo Tanamachi, son of Kumazo and Asao Hirayama Tanamachi, was born on April 1, 1917 in Long Beach, California. His hometown was San Benito, Texas. Saburo was the fourth born of twelve siblings — Jack Ichiro Tanamachi, Jerry Tanamachi, Fumiko Onishi, Saburo Tanamachi, Goro Tanamachi, Willie Tanamachi, Rene Tadano, Walter Tanamachi, Yuri Nakayama, Masako Elliott, Mary Mariko Otsuki, and Hiroko Edwards.

Saburo attended Beaumont Elementary School and graduated from Beaumont Junior School and Brownsville High School. He was a member of the Brownsville High School football team. Saburo was a farmer before being drafted, and his goal was to become a progressive farm supervisor.

Saburo was drafted (Serial No. 38 562 665) in February 1944. After completing his basic training in Camp Blanding, Florida, Arnold went overseas and served with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, 2nd Battalion, Company E.

Private First Class Saburo Tanamachi was killed in action by a bullet wound on October 29, 1944 during the Lost Battalion Rescue on Hill 617 in the Vosges Forest near the vicinity of Biffontaine, France.

Saburo’s sister Yuri Nakayama wrote, “. . . He (Saburo) was an excellent student and our Dad was very proud of him. He excelled in all sports. He worked hard on the farm to help with the crops. When our oldest brother Jack moved to Los Angeles to help out an Uncle, Saburo took over as planner of the crops and crop rotation. He kept the wheels in gear and saw that the planting seeds were bought, fields plowed and prepared on time. He did the payroll, saw that things went to market, the cotton picked and taken to the gin, and the arm land lease was paid. Dad often commented

on how well he could organize and schedule, like a fine tuned watch. We greatly missed him when he was drafted. He wrote home describing the people and the area farms, how clean and neat France was, how war torn Italy was. He promised he would bring me home Hitler’s mustache, so I didn’t expect to get that letter from the War Department saying, we regret to inform you that Saburo was killed October 29 near the city of Biffontaine, France, 1944 . . . .”

Saburo’s comrade Private George “Joe” Sakato, Medal of Honor recipient, wrote, “ . . . And he (Saburo) was shot and fell into his fox hole. I crawled out of my fox hole and into his and picked him up and held him tight and cried, “Why?” He tried to say something, and his body went limp on me. Then I knew that he died. I was so mad and while crying, I jumped up and picked up my Thompson Submachine gun and charged up the hill running as fast as I could zigzagging all the way and firing the Thompson as I ran. . . We did take the hill, and I went back to Saburo and took the 1921 silver dollar that he carried and gave it back to his mother when I returned home. . . .” Private First Class Saburo Tanamachi was posthumously awarded the Silver Star, Purple Heart, and the Combat Infantryman’s Badge.

Published September 10, 2006

Saburo Tanamachi, an American of Japanese descent, died fighting to save fellow American soldiers during World War II. Sixty years later in 2004, Sandra Tanamachi, Saburo’s niece, won her 12-year fight against injustice when Jefferson County commissioners voted to assign a new name to a rural street known for too long as Jap Road.

The family’s struggles for justice and the sacrifices they made are featured in a new book, “Just Americans: How Japanese Americans Won a War at Home and Abroad,” by Robert Asahina. The book tells the story of the 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team, a racially segregated unit of Japanese-American soldiers during World War II, from their fights on the battlefield to their struggles to be accepted as loyal American citizens.

Asahina said it was the historical link between what Sandra Tanamachi — now a resident of Lake Jackson — has been doing the past 10 to 12 years and what her uncle did in World War II that led him to include them in his book.

“I found the symbolic link quite striking, that this man died fighting injustice, and now his relative had likewise fought to battle injustice 60 years later,” Asahina said.

Saburo Tanamachi was a member of the 442nd when the unit rescued the “Lost Battalion” in late October of 1944. The Lost Battalion was made up of 211 men from four companies of the 141st “Alamo” Regiment of the 36th “Texas” Division. They were stranded in the Vosges Mountains of eastern France, behind German lines, without food or ammunition. It took members of the 442nd four days of hard fighting to reach them, and Saburo’s unit sustained casualties greater than the number of men they rescued. He was one of those killed in the fighting.

For their heroism, members of the 442nd were named honorary Texas citizens by the Texas governor at the time. Saburo Tanamachi was awarded the Silver Star and the Purple Heart posthumously. Originally buried in France, he was later one of the first two Japanese-American soldiers to be interred in Arlington National Cemetery.

General George C. Marshall called the 442nd the “most decorated unit in American military history for its size and length of service.”

Asahina said the wake of the September 11 attacks spurred him to write about the 442nd. “I thought it had a real relevance about how minorities are integrated into American life, the sacrifices that are required of them and the ones that they make willingly,” the author said.

Part of what was remarkable about the soldiers of the 442nd was that many had volunteered to join the Army from “relocation camps” where they and their families had been incarcerated after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Sandra Tanamachi’s mother was one of those whose family was sent to an internment camp in Arkansas.

“She told us it was horrifying,” Tanamachi recalled. “My mother was born and raised in California. She, just like all Americans, was just appalled by what happened December 7, 1941, but because of their heritage, (her family) were interned. They were only given 48 hours to move out, and could only take what they could carry with them.” When the family was first removed from their home the camps weren’t ready to be occupied yet, so they were put in Santa Anita race track, in a whitewashed horse stall.

“My mother said you could still smell the horses and the manure,” Tanamachi said. Many elderly people and children got sick in those conditions. The family lived there for six months before they were put on a train and sent to Arkansas.

“(The camp) was completely surrounded by barbed wire and they were guarded. They were held like prisoners, but they hadn’t committed any crime. Even in that situation, the young men volunteered,” Tanamachi said.

Besides Saburo, Sandra Tanamachi had three other uncles who served in the Army during World War II.

“They told me they fought for the United States so that the country would become a more understanding place for them,” she said. “They were American citizens. They all joined the Army to prove their loyalty as Americans.”

Decades after the end of the war, in the 1990s, Sandra Tanamachi and her husband moved to Jefferson County, near Beaumont. Her grandparents had settled in the town in the 1920s, and her father played football on the high school team. It was like coming back to her roots, in a way.

But then she learned of the existence of Jap Road. It was impossible to ignore the racial slur, when a catfish restaurant located on the road emblazoned its address on billboards and television ads. On her own, Tanamachi approached the Jefferson County Commission, asking them to rename the road. Only one commissioner voted in support of her plea.

She was told the road was named in “honor” of a Japanese rice farmer who had lived there in the early 1900s, a Mr. Yoshio Mayumi. He had earned the liking and respect of his neighbors, but they allegedly couldn’t pronounce his name. So his farm was known as “the Jap farm,” and the road was likewise named. To change the name would be an expense, and would be troublesome for residents who would have to change their mailing addresses, Tanamachi was told.

But she wasn’t ready to give up. She wrote a letter about the situation to the Japanese-American Citizens League, but was so nervous about raising trouble, she didn’t sign her name.

“At the beginning I didn’t want my name involved with it, I just wanted it changed,” she said. The Japanese-American Citizens League functions like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or the League of United Latin American Citizens.

“I thought once they saw it, they would work on it,” Tanamachi said. “But nothing was done. I think they were too afraid. I decided I just had to put a face to it and start working on it myself.”

She found a handful of like-minded citizens and the campaign to rename Jap Road began. Civil rights organizations and even newly elected president Bill Clinton pledged support, but there was opposition as well. Residents said changing the name would be losing a part of their history, and resented the idea of “outsiders” trying to change things.

As the campaign reached the papers, she began to get harassing phone calls. Notes left in her mailbox at the school where she worked told her to “get a life.” Her home mailbox was shot up by vandals.

She says it was the memory of her family and support from her uncles that helped her to continue.

“I have four uncles who are American veterans. I didn’t want their sacrifices to be in vain,” Tanamachi said.

As the fight over Jap Road heated up, it drew national attention. The New York Times picked up the story.

Meanwhile, Robert Asahina started writing his book.

“I started working on it in 2001,” he said. “I didn’t know about this struggle she’d been going through for years, or that it was going to come to a head in 2004. I read about it in the newspaper, and I thought, ‘Boy, this is remarkable, that the relative of a soldier I knew about through my research was going through this fight 60 years later.’”

He contacted Sandra Tanamachi through the Japanese-American Citizens League, and followed the progress of her campaign.

Finally, in the summer of 2004, Jefferson County commissioners again were set to vote on changing the offensive road name. Though she now lived in Lake Jackson, Sandra Tanamachi was there with her family, including her uncle Willie, who is an Army veteran and a Beaumont native, and Saburo’s younger brother. Roughly 150 people attended the meeting, and the crowd was clearly split over whether to rename the road or not. That night, commissioners voted unanimously to rename the road, and to let the citizens choose a new, non-offensive name. The residents decided to name the road after the now-defunct catfish restaurant whose ad campaign had been so ubiquitous in the 1990s: Boondocks.

Two months later, another Jap Road in Fort Bend County changed its name, and in 2005, another was changed in Vidor. “We no longer have any roads like that in Texas,” Tanamachi said. The process was a lot quicker in the other two counties than it had been in Jefferson County.

“Everyone was watching,” Tanamachi said. “I don’t think they wanted to go through what Jefferson County went through.”

She said Asahina’s book told an important story. “He told a lot of stories that weren’t told before,” Tanamachi said. “The book was important so that American public would learn more about the many sacrifices of Japanese-Americans, so that there would be no question as to their loyalty.”

Sandra’s uncle Willie Tanamachi, 85, is the last of four veterans. He’s been reading parts of the book.

“I know he’s very happy that the story’s in there, and that the public can learn more about it,” Sandra said.

As for Yoshio Mayumi, though Boondocks Road residents declined to honor his memory by naming the road he once lived on after him, the state of Texas has been more mindful. It is working on a historical marker to be erected near the Mayumi farm.

Washington, May 30, 1948– Two soldiers of the 442nd Japanese American Regimental Combat Team, one from Los Angeles and the other from San Benito, Texas, will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery, the shrine of national heroes, on Friday, June 4, the Public Information Division of the Army Department and the Washington office of the JACL Anti-Discrimination Committee announced in simultaneous releases today. They will be the first persons of Japanese ancestry to be interred in the national cemetery.

High military and civilian government officials, including General Jacob L. Devers, Chief of the Army Field Forces, four other generals, and a number of Congressmen, will be Among the unprecedented number of persons to pay final homage to the two Nisei heroes. Representatives of the National Japanese American Citizens League, the Washington JACL Chapter, the JACL Arlington Cemetery Committee and the local Japanese community will Lay wreaths at the graves.

The two soldiers are Privates First Class Fumitake Nagato, son of Sunzo Nagato, Now of 2037 South 12th Street, Arlington, Virginia, and Saburo Tanamachi, son of Kumazo Tanamachi, of San Benito, Texas. Both men were killed on October 29, 1944, while engaged In the historic rescue of a “lost battalion” of the 36th (Texas) Infantry Division from a trap in The Vosges Mountains of Eastern France. Their remains were returned to the U.S.Iast month Aboard the funeral ship Lawrence Victory and are being interred at the national cemetery in Compliance with the wishes of the next-of-kin.

Among those attending the funeral rites will be many officers who had intimate association with members of the Japanese American combat team. The presence of such an unusual Gathering of military officials is an expression of the esteem in which Nisei soldiers of that unit Are held by the Department of the Army. The 442nd, the most decorated unit in the U.S. Army, Fought with distinction in every action it was called upon to undertake.

The Vosges engagement in which Nagato and Tanamachi gave their lives was one of the Outstanding small unit campaigns of the war. In rescuing the lost battalion, of which 189 remained alive at the conclusion of the engagement, two battalions of the 442nd lost more than 200 killed and 800 wounded. The final charge which resulted in the rescue of the beleaguered Battalion was led almost entirely by enlisted men of Japanese ancestry after nearly all the Battalion’s officers became casualties.

The Department of the Army which is making the ceremony an occasion of great significance has designated the following to be honorary pallbearers; General Jacob Devers, Army Ground Forces Chief, who commanded the Sixth Army Group under which the 442nd fought in France; Major General John E. Dahlquist, Deputy Director of Personnel and Administration, Army General Staff, who commanded the 36th Division in the Vosges; Major General Robert R. Gay, Commanding General of the Military District of Washington, D.C.; Majoe General George A. Horken, Chief of Memorial Division, Office of the Quartermaster General who is operating head of the Return of World War II Dead program.

Other Army-designated pallbearers are: Colonel Virgil Miller, Professor of Military Science and Tactics at Penn State College, who commanded the 442nd in the Vosges battle; Colonel Charles W. Pence, of Fort Benning, Georgia, Commander of the 442nd until he was wounded in the Vosges engagement; Colonel Charles H. Owens, Commanding Officer of Fort Lesley J. McNair, Washington, D.C. and wartime commander of the 141st Infantry Regiment, parent unit of the “lost battalion” ; Colonel James Notestein, of Public Information Division, Army Department, whose infantry regiment in Italy fought beside the 442nd, and Lieutenant Colonel James M. Hanley of the Judge Advocate General’s Office, formerly executive officer of the 442nd.

General Mark W. Clark, of 5th Army fame and now Commanding General of the Sixth Army, will be unable to attend, but indicated he is preparing a message to be sent on the occasion. The military religious services will be conducted by Major General Luther D. Miller, Army Chief of Chaplains, and the civilian services will be conducted by the Rev. Andrew Kuroda.

The honorary pallbearers invited by the Japanese American Citizens League to include: Representative Ed Gossett, Democrat of Texas, Gordon L. McDonough, Republican from California and Walter H. Judd, Republican from Minnesota; Joseph R. Farrington, Congressional delegate from Hawaii; the Honorable John J. McCloy, President of the World Bank; Dillon S. Myer, wartime head of the War Relocation Authority; Mike Masaoka, national legislative director of the JACL ADC; Ira Shimasaki, president of the local JACL chapter, and J.S. Shima, head of the Japanese American Society of Washington.

In commenting on the funeral services for Nagato and Tanamachi, Congressman Gossett of Texas declared: Texans are glad to honor the 442nd Regimental Combat Team along with her famous 36th Division. in death, Privates First Class Fumitake Nagato and Saburo Tanamachi served two causes. They glorified and helped to save American institutions. They also glorified Japanese American citizenship. Our nation is doubly proud of them.”

Congressman McDonough said: “Their services to our country shall never be forgotten and shall continue to serve as an inspiration to all that true Americanism is not a matter of race or ancestry but a matter of the mind and the heart.”

Brief eulogies will be delivered by General Devers, Congressmen Gossett, Judd and McDonough, Mike Masaoka and Mr. Shima.

TANAMACHI, SABURO

PVT INFTY WW II

- DATE OF BIRTH: 04/01/1917

- DATE OF DEATH: 10/29/1944

- BURIED AT: SECTION 12 SITE 4845

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard