Elbert Wayne Bush

Sergeant, United States Army

Richard Arthur Knutson

Chief Warrant Officer, United States Army

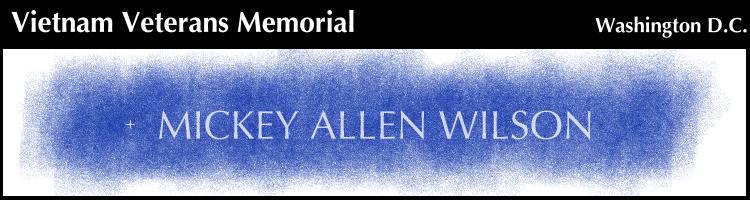

Mickey Allen Wilson

Chief Warrant Officer, United States Army

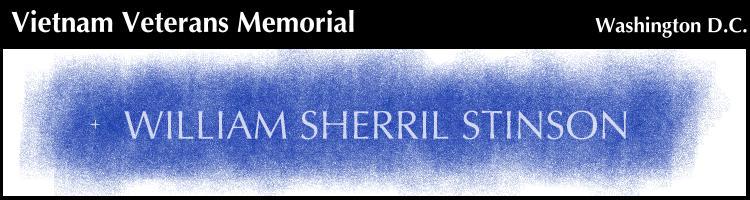

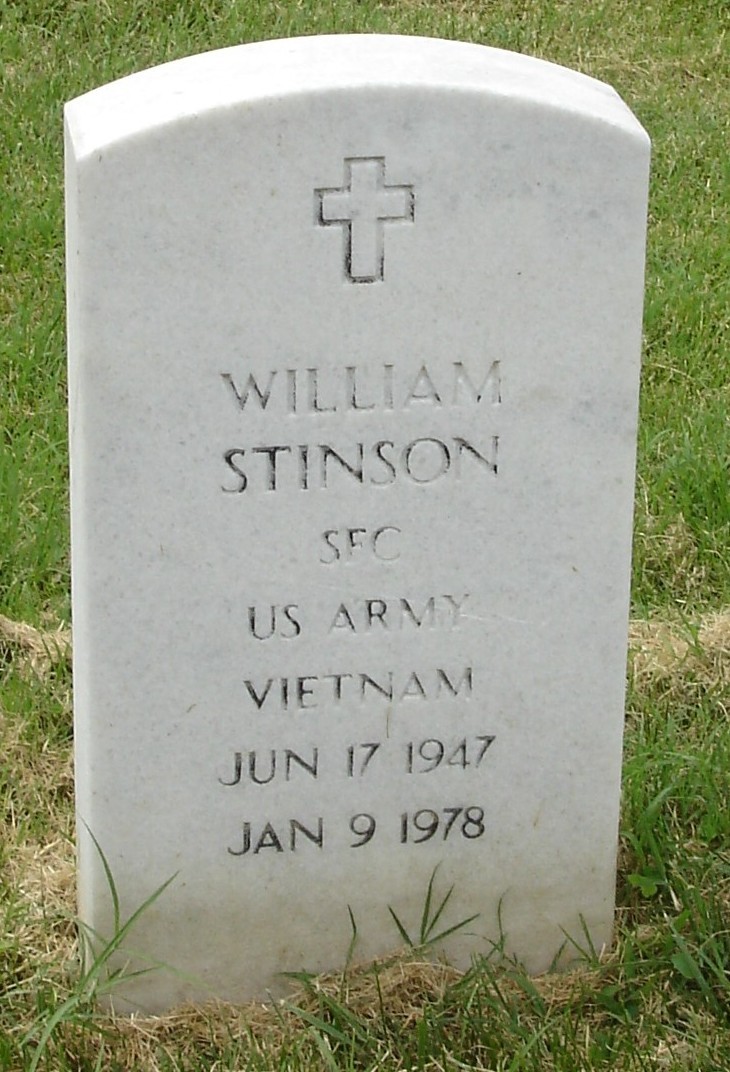

William Sherril Stinson

Specialist 5, United States Army

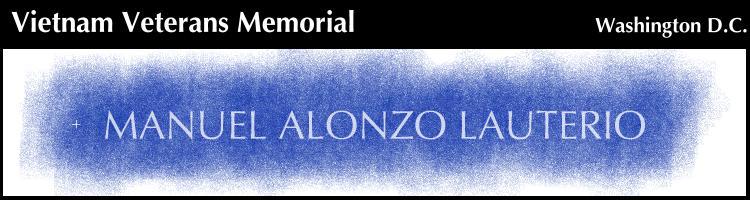

Manual Alonzo Lauterio

Specialist 5, United States Army

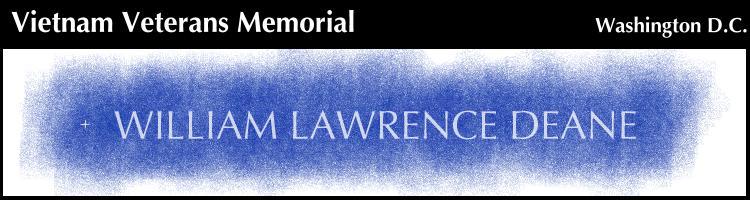

This group of men were finally located and identified. Sadly, the remains of Manual Alonzo Lauterio and Richard Arthur Knutson have not yet been found or identified. The remaining three crewmembers were buried together in Section 60 of Arlington National Cemetery on Friday, 14 April 2000.

Photograph By M. R. Patterson, October 2002

“I once was lost but now I’m found.”

SYNOPSIS: WO1 Richard Knutson, pilot; WO1 Mickey A. Wilson, Aircraft Commander; SP-5 William S. Stinson, Gunner; SP-5 Manual A. Lauterio, Crew Chief; and Staff Sergeant Elbert W. Bush and Major William L. Dean, both passengers, were aboard a UH1H helicopter (serial number 69-15619) that flew in support of the American Senior Advisor to the Vietnamese Airborne Division in Quang Tri and Thua Thien Provinces, working between the provincial capitals of Hue and Quang Tri.

On January 8, 1973, at about 1430 hours, the aircraft had departed a landing zone enroute to other landing zones without making radio contact with the Second Battalion Technical Operations Center. When no radio contact was received by 1500 hours, the other landing zones were queried. The helicopter did not go to either of the two designated landing zones, nor had any communication been established with them.

The helicopter’s intended route would have taken it northwest toward Quand Tri, with a left turn to a landing zone South of the Thach Han River. Although the helicopter failed to contact either landing zone along the route, it was later seen flying toward Quang Tri City and crossing the Thach Han River into enemy-held territory. While in this area, the helicopter was seen to circle with door guns firing. Enemy automatic weapons fire was heard, and a direct hit was made on the tail boom by a missile, reportedly an SA-7.

Aerial searches of the suspected crash site on January 8 and 9 failed to locate either the wreckage or the crew. The aircraft was shot down less than three weeks before American involvement in that war came to an official end. Intelligence reports indicated that of the six men aboard, four were seen alive on the ground. Further information indicated that the aircraft did not explode or burn on impact with the ground. The families of the men assumed that their loves ones would be released with the other POWs. Some were even so informed.

But the crew of the UH1H was not released, and have not been released of found since the day of the incident. As thousands of reports of Americans alive in Southeast Asia mount, these families wonder if their men are among the hundreds thought to be still alive.

For the past five years, this crew has been my adopted MIAs. Now they are home. Click here for their adoption page.

From a press report: April 2000:

For two Medford, Oregon, sisters, national POW/MIA Recognition Day is a time for

tribute and a time for change.

On Friday, Linda Moreau and Sandra Zito will pause and pay respect for their brother, pilot Mickey Allen Wilson, who was listed as missing in action when his helicopter was shot down in Vietnam on Januart 8, 1973.

And they will work toward changing the way the U.S. government notifies next

of kin in MIA and POW cases.

“It may have been 28 years since it happened, but it seems like yesterday to us,” said Moreau, 50. “When you look at Mickey’s picture, he’s still 24. He never ages.”

“Most of our veterans didn’t want to be in Vietnam,” said Zito, 48. “They went over there because their country sent them. We can’t walk off and forget them.”

It wasn’t until late this summer that they learned via the Internet that their brother’s remains had been buried April 14 in Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C. Only their elderly parents, who live in Washington state, were notified and attended. Their parents had not elected to notify other family members of the ceremony.

“We respect the fact our parents wanted their privacy, but we still wanted to be there,” Moreau said. “We needed the healing, the closure.”

In the future, the sisters hope that Uncle Sam will, when the parents are elderly, also notify the adult siblings. A younger brother, Jack Wilson, who lives in California, had not been told about the ceremony, either.

A spokesman at the U.S. Army’s MIA/POW Affairs office explained that the current law requires the military to notify only the primary next of kin.

That includes parents or, if married, the spouse, he said. If the parents are deceased and the veteran is not married, the primary next of kin would be the oldest sibling, he said.

There were 3,307 American servicemen missing in action at the end of the Vietnam War. Of those, 2,008 remain unaccounted for, according to the POW/MIA Affairs office.

Wilson was listed as an unaccounted-for MIA until his remains were found in 1996, officials report. A UH-1H Huey helicopter pilot, he and five others were shot down near Quang Tri just 23 days before the Paris Accords were signed, marking the end of American participation in the war.

His remains were positively identified last October at the Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii, making him one of 1,299 MIAs accounted for, according to the government.

Yet he was never a statistic to his family. His cousins in the San Francisco Bay area kept a bottle of wine in their refrigerator for 12 years, waiting for the day he would return home alive, the sisters said.

Moreau also spent five years tracking down information about her brother. The family knew he had married a Vietnamese woman named Mary on December 7, 1972, with whom he had a baby son. But Wilson’s widow and son disappeared in the mass confusion at the end of the war.

She eventually tracked down her sister-in-law, who now lives in Tennessee. Moreau’s book, “Danang to Memphis,” published early this year, relates the remarkable tale.

Last week, Moreau received a telephone call from a veteran in Connecticut who had just read her book. He had served with their brother in the military.

“Mickey touched many lives, not just ours,” Zito said. “There are numerous friends of Mickey’s as well as members of the family who wanted to be there. They would have been there in an instant to honor Mickey had we been allowed to know about it. We all had the right.”

Her sister agreed.

“It wasn’t just Mickey I wanted to honor and say goodbye to,” Moreau said. “It was also Bush, Deane, Stinson, Knutson and Lauterio.”

Elbert W. Bush, William L. Deane, William S. Stinson, Richard A. Knutson and Manuel A. Lauterio were the other soldiers aboard the aircraft that day.

Zito was at her parents’ home in 1996 when they were notified that his remains had been found.

“They were completely devastated,” she said. “I was there because I had asked Dad if I could be there. They didn’t ask any questions or look at the report. It was too painful for them.”

It was just as painful to be notified of their brother’s funeral ceremony by Internet after the fact, Moreau said.

“I was looking on the Internet and here’s a story about our brother being buried at Arlington,” Moreau said. “To find that out after all we had gone through in the last five years — the heartaches, the pain, the happiness — was very difficult.”

They hope the federal government will hold another ceremony for immediate family members who had not been notified.

“We want another service for Mickey,” Zito said. “We want the opportunity for everyone who wants to, to be there. We want closure.”

“I’m very patriotic,” Moreau added. “The sight of an American flag still makes chills go up my spine. That’s just the way we were raised.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard