To Contact This Fine Organization, Click Here

One good test of a new work of architecture is the degree to which it improves its surroundings. By this measure, the Women in Military Service for America Memorial is a resounding success. Even though it is a bit too reticent, the memorial enhances an already splendid setting in a number of ways.

You approach via Memorial Drive, on that unforgettable visual axis between the Lincoln Memorial and Arlington National Cemetery, with the Greek columns of Arlington House on the green western hill. The new memorial — being dedicated today — is at the base of the hill.

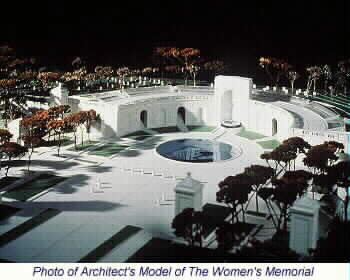

From a distance you would hardly know it is there, for the memorial has been subtly built in front of, on top of and behind an existing structure — the elegant semicircular stone retaining wall that for more than six decades has marked the ceremonial entrance to the cemetery. At dusk there is now a soft glow atop the wall, from the electric light coming through the memorial’s canted glass roof.

Up close, you notice the transformation right away. In front of the wall is a handsome stone-paved plaza with a dark circular pool in the center. The wall itself, left untended for decades, once again shines crisply under the autumn sun. Four of its 11 blind niches have been opened up for stairwells leading to the roof. There, you’ll find a newly paved walkway and angled glass “tablets,” many engraved with sayings about women’s experiences in the military. Behind the wall a new building has been dug into the hillside, housing pertinent displays, a hall of honor, a small auditorium, a shop and a computerized service registry.

Designed by the New York wife-and-husband architectural team of Marion Weiss and Michael Manfredi, the memorial is insistently respectful of its honorary place, and therein lies its greatest strength. We are correct to worry about building too many memorials in Washington, but this one looks right and feels right in this particular spot because it is part of a larger whole. The symbolism of the nation’s most sacred military resting place contributes to the resonance of the new memorial, and vice versa.

Of course, a bad design or even a somewhat less sensitive one would have upset this balance. Weiss and Manfredi “read” the site perfectly. Their interventions, though quite extensive, are understated and ingenious. Likewise, the precision of their low-key, minimalist detailing — the metal fixtures holding up the glass “tablets” are engineered as if for a sailing ship or supersonic aircraft — are an ideal complement to the dry classicism of the original wall.

There are, however, two major flaws. One is the very idea of combining memorials with museums — or interpretative centers or recruiting stations or whatever you want to call the spaces attached to this memorial and several others recently built or proposed. The circumstantial facts that this particular “museum” is hidden behind an existing wall, and is nicely designed, do not change the logic: Memorials are not exhibition halls. The functions and spatial needs of the two are very different.

A good rule of thumb might be that if you have to spend a lot of time and space to explain why a memorial exists, then perhaps you ought to think about building something else. In this case, there was no overwhelming need to explain the memorial: Female vets deserve a special place in Arlington Cemetery, but most of the other stuff — gallery, auditorium and so on — is extraneous.

The only big fault in the design — the lack of a distinctive imprint from afar — is not the architects’ fault. In their 1989 competition-winning design, the pair proposed a series of tall, thin glass pyramids atop the wall; these, too, would have brought natural light by day into the exhibition halls below, and at night would have sparkled like distant candles on the dark hill. This poetic touch, however, was excised by the bureaucracy; it was felt, some said, that the “candles” would have detracted from the solemnity of the cemetery. One could argue the opposite but, in any case, we’ll never know.

Credit Weiss, Manfredi and, especially, retired Air Force Gen. Wilma Vaught — the definitive mother of this memorial — for perseverance. The architects were distraught after that setback but Vaught picked them up with her stick-to-itiveness, and the designers then came up with a creative alternative — the glass tablets. These rectangular panels of thick, transparent glass (each capable of sustaining an 800-pound load) are tilted upward at an angle of about 20 degrees and arranged around the balustraded top of the hemicycle.

The tablets are effective on several levels. They open what could have been a gloomy underground building to the sky and to changing conditions of natural light. The inscriptions are moving and apt. (One of my favorites is a straightforward statement by World War II Coast Guard Capt. Dorothy Stratton: “We wanted to serve our country in its time of need. The Coast Guard gave us this opportunity and we did our job well.”) And the shadow effects are wonderful and fitting: Through the day, as the Earth changes position in relation to the sun, the inscriptions are cast in shadow on a white marble wall. At differing angles, sometimes they are readable, sometimes not.

These adroit uses of light and shadow are two of the ways the architects reinforced the meaning of the memorial. Water, with its connotations of healing and contemplation, is another key element: A multi-jet fountain is cupped by the half-dome of the wall’s large central niche; from it, the water flows in a black granite trough to the quiet circular pool in the middle of the plaza. Whether seen from above or experienced at ground level, it is a simple, affecting arrangement.

The interiors are uncomplicated and unostentatious. A long gallery follows the sweeping curve of the wall. Metal canopies and display cases, sympathetically designed by Staples & Charles of Alexandria, will eventually fill 14 of the 16 alcoves on the curve’s inner arc; for the opening, three cases devoted to World War II have been installed. Ancillary chambers (store, auditorium, etc.) open off the opposite wall.

Weiss and Manfredi wisely left exposed the retaining wall’s rough concrete surfaces. These set the tone for the low-key palette of steel and glass, blond wood counter tops, polished concrete floors and that symbolic white marble wall. A serious atmosphere prevails. In this long, curved room visitors will be aware that they are under the earth but, thanks to the transparent ceiling and the glass-walled stairwells that slice through at regular intervals, they will not lose sight of the outdoors.

The semicircular retaining wall was designed in the late ’20s by William Mitchell Kendall of McKim, Mead & White — probably the best known architecture firm in the land during the early years of this century — as part of a notable spatial sequence that includes Memorial Bridge. The wall identified the cemetery’s entrance and, from a distance, reinforced the formal vista linking the cemetery to the Lincoln Memorial. But it was never much of a place to visit, and it became something of an elegant ruin.

Now, thanks to a brilliant, sensitive design, the wall has gained in stature both literally and symbolically. All cleaned up, it once again performs its important visual function with distinction. In addition, it has been transformed into a memorable public place. From its balustraded roof we now can focus our attention on the specific issues of women’s military service, and then, as at all successful memorials, on larger matters.

Astronauts | Biograpies | Burials | Civilans | Contacting Arlington | Custer | Foreign Nationals | Gravesites | Guest Book | Home | Images | Inquiries | Things to See | US Air Force | US Army | Coast Guard | US Marines | US Navy | Visiting Arlington | Webmaster

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard